A Guide to On-Farm Processing for Organic Producers: Table Eggs

The Kerr Center has published a new book Farm Made: A Guide to On-Farm Processing for Organic Producers, which offers advice on four example enterprises, one of which is table eggs. The chapter is written by Anne Fanatico and George Kuepper.

Farm Made: A Guide to On-Farm Processing for Organic Producers by George Kuepper, Holly Born and Anne Fanatico has been published by published by the Kerr Center for Sustainable Agriculture and co-distributed by the Kerr Center for Sustainable Agriculture and ATTRA, the US National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service. Funding was provided by the Organic Farming Research Foundation.

Table Eggs: The Basics

What are table eggs?

Table eggs or shell eggs are eggs in the form most familiar to consumers – fresh and in-the-shell. Though commercial table eggs may come from a variety of birds, and many of the procedures are the same, this discussion will focus on chickens. It also focuses on relatively small operations, particularly those with direct-to-consumer sales or sales to local restaurants and retailers.

Farm production basics

Acquiring chicks. Farmers typically purchase day-old chicks from hatcheries or distributors that work with hatcheries. Shipping is usually done via USPS or UPS. Sometimes chicks may also be purchased from local farmers co-ops and farm suppliers. It is wise to order only pullets (female birds less than one year old), unless the producer also wants to raise males for slaughter. Depending on the cost of feed, it may be more economical to buy started pullets, which are birds old enough to lay eggs (about 20-22 weeks).

Brooding. It takes up to eight weeks for chicks to 'feather out' and they are especially delicate and vulnerable for the first three. Chicks must be raised in brooder boxes equipped with lamps for heating and which provide protection from drafts, predators, and excessive handling. Non-slippery bedding is required to prevent 'spraddle legs'. Growers recommend rice hulls, wood shavings, ground corn cobs, and similar media. Close confinement is desirable for warmth, though at two weeks or so, the need for space will increase as the birds begin to grow rapidly.

Appropriate food, clean water and grit must be available from the outset. Pullet feed should contain 18 per cent protein for the first eight weeks, and be reduced to 16 per cent from then up until laying.

Layer housing. Even free-range poultry requires some form of housing to provide nesting sites for laying and roosting, to provide protection from the elements and predators, and to ensure the comfort necessary for productive laying.

A minimum of one-and-a-half to three square feet of floor, per hen, is recommended. There should be one nest box for every four to five hens, located two feet above the floor litter. Allow six to eight inches per bird for roosting space, with the poles spaced 12 to 14 inches apart and 18 to 36 inches above the floor litter 6,7.

Layer management and nutrition. Once laying begins, pullets should be switched to a laying ration that contains 16 to 18 per cent protein with 3.5 per cent calcium. Floor litter should be three to six inches deep, low dust and kept reasonably dry. Wet litter should always be removed.

Day length can be managed to stimulate laying. At 18 weeks, pullets should be placed on 14 hours of daylight. When half of the birds have begun laying, it should be adjusted to 16 hours 8.

The laying cycle for a chicken flock is usually 12 months. Production peaks at around six to eight weeks, then slowly declines. In commercial production, hens are either destroyed or processed at 70 weeks, or they are forced to molt. Moulting is a natural process in which birds renew their feathers and replenish their bones and reproductive systems. During moulting, egg laying declines further or ceases entirely. Following forced molting, the hens can resume production and are often kept up to 105 weeks of age.

Egg collection. Eggs should be collected twice a day, more often if weather is extremely hot or cold. Immediately discard any cracked or misshapen ones. Promptly cool eggs to 45°F as eggs held at room temperature rapidly lose grade. Store them with the small end down 9.

On-farm processing basics

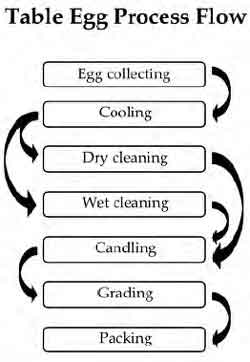

Ideally, eggs are processed the day after they are laid. The USDA requires processing within 30 days of lay. In programmes that assure high quality, eggs are processed within seven days of lay.

Cleaning. Discard eggs that are very dirty. If eggs are washed (wet cleaned), the wash water should be about 20°F warmer than the eggs. This encourages the contents to swell and push dirt out of the pores. Water of equivalent or lower temperatures can draw contaminants into the eggs; much higher temperatures can lead to cracking.

Water exposure should be as brief as possible to reduce the possibility of contamination.

Mild cleaning agents are sometimes used in wet cleaning. Eggs should be dried as soon as possible.

It is unusual, but wet cleaning is prohibited by state regulation for some markets. Specifically, Minnesota regulations prohibit the sale of wet-cleaned eggs to stores and restaurants 10. Immersion washing is especially frowned upon and may be specifically prohibited. Dry cleaning using a brush, sandpaper, or a loofah sponge has fewer issues than wet cleaning, and is recommended for small producers.

Preventing dirty eggs through better management of the hens and their nesting space will greatly reduce the need for cleaning the eggs. (See Plamondon's 'Egg Quality/Egg Washing' web page.)

Candling. Candling is a means for assessing the interior quality of eggs. The name hearkens back to the days when an egg was held up in front of a candle to reveal the inside. Today, a high-intensity light is used. Interior quality is determined by the size of the air cell (the empty space between the white and shell at the large end of the egg, smaller in high-quality eggs), the proportion and density of the white, and whether or not the yolk is firm and free of defects 11.

Candling will also reveal cracking: cracked eggs should not be sold. Farm-scale equipment for candling can be homemade or is available through farm supply outlets such as NASCO.

Grading. The primary USDA egg grades are AA, A, and B. Grades are based on both exterior and interior quality. For specifics on egg grading, see the USDA-AMS Poultry Programs web site.

Grading also involves sorting eggs into weight classes or sizes (peewee, small, medium, large, extra large and jumbo). The USDA Egg Grading Manual details what an egg of a specific class needs to weigh. Many producers do not grade but mark their eggs as mixed, unclassified, or ungraded. Farm-scale equipment for grading is available through farm supply outlets such as NASCO.

Packaging. Eggs may be carton-packed according to size or as unsized. Standard packaging for direct sale is by the dozen, half-dozen, or dozen-and-a-half. Cartons are typically made of pulp paper, styrofoam or clear plastic.

Labelling. Eggs packed under federal regulations require the pack date to be displayed on the carton. It is a three-digit Julian date that represents the consecutive day of the year. The carton is also dated with the 'Sell-by' or expiration date, which depends on the state requirements. Eggs with a federal grade must be sold within 30 days from day of pack 12.

Organic Issues

Organic production issues

Obtaining chicks. For any poultry to be considered organic, it must be managed as such beginning no later than the second day of life. Therefore, the standard practice of buying day-old chicks from conventional hatcheries presents no problem. However, organic growers do not have the option of using starter pullets, unless they came from a certified organic grower.

Whether the organic farmer seeks a niche market for coloured eggs, or chooses to produce standard white eggs, the issue of breed selection is important. The National Organic Standard stipulates that breeds should be chosen for disease resistance and suitability to site and operation. However, high-yielding genetics are typically used in both conventional and organic poultry production, with consequences. High-yielding birds can lay over 300 eggs per year but may also develop osteoporosis or brittle bones. There is increasing interest in using heritage breeds for organic production.

Fortunately, selection for egg production has been common with heritage breeds in recent decades, and good utility strains exist. For further information, read ATTRA's Poultry Genetics for Pastured Production.

As technology advances, genetically engineered and cloned birds may become available. These are prohibited in organic production.

Brooding. The National Organic Standard §205.239(a)(1) requires outdoor access for all organic livestock. This does not apply to brooding chicks. Confinement brooding is a proper and good example of temporary confinement as allowed under §205.239(b).

While many conventional growers provide chicks with a medicated starter ration while brooding, this is not allowed in organic systems. Organic management requires 100 per cent organic feed. Chick starter feeds, as well as all feeds provided at later stages of life, must be certified organic.

Layer housing. Housing should protect birds from the elements, maintain a comfortable temperature, provide ventilation and clean bedding, and allow birds to exercise and conduct natural behaviors. Cages are not permitted.

In addition, the birds must have access to the outdoors for exercise areas, fresh air, and sunlight, and must be able to scratch and dust-bathe. According to §205.239(b) of the National Organic Standard, livestock may be temporarily confined due to inclement weather, requirements of the stage of production (e.g. brooding), conditions under which the health, safety, or well-being of the animal could be jeopardised, or risk to soil or water quality. Many certifiers allow confinement during cold weather. However, some breeds are quite hardy and will venture outdoors if allowed.

Wire and all-slat flooring is generally not permitted; some solid flooring with litter should be maintained so birds can scratch. If birds are likely to eat their litter, it must be organic to comply with the requirement for 100 per cent organic feed.

Litter treatments, such as sodium bisulfate and hydrated lime, are common in conventional production to lower pH, reduce microbial growth, and control ammonia production. These are synthetic materials that are not allowed in organic production. If litter treatments are used, they must be either non-synthetic or be made from synthetics allowed for that purpose on the National List. (Hydrated lime is on the National List but is restricted to use as a topical treatment for external pests.)

Where used, treated lumber must not contact the birds, eggs, feed, or soil they traverse. For guidance on alternatives, read ATTRA's Organic Alternatives to Treated Lumber.

In practice, the requirement for outdoor access has resulted in a wide array of housing options and a fair bit of confusion over how much space and time outdoors that birds should have. At least one certifier has approved a system wherein outdoor access is limited to enclosed porches. At the other extreme are some pasture based systems where birds not only go outside, but have abundant forage.

The National Organic Standard does not specify indoor or outdoor stocking densities, but many organic certifiers look for a lower stocking rate than the industry average of 0.7 square feet per bird; most look for at least 1.5 square feet per bird.

There is no limit on the number of birds that may be raised in one house; nor is there a requirement for the number of bird exits or 'popholes' that should be provided.

Furthermore, how much outdoor access a bird should have during its lifetime is not specified under the Standard.

Layer management and nutrition. Feed must be 100 per cent organic, whether produced on-farm or purchased. It may contain only those synthetic additives and supplements found on the National List. No animal drugs, antibiotics, or slaughter byproducts are allowed in organic feed. Feed rations must provide the levels of nutrients appropriate to the type of bird, breed, and age/stage of development. Any pasture or free-range areas must have been free of synthetic chemicals for three years.

Synthetic amino acids are prohibited in organic production, with the exception of synthetic methionine, which will be allowed until 1 October 2010. Providing adequate methionine in poultry diets can be challenging when birds do not supplement their diet with free-range foods like insects and earthworms. Supplementing with methionine-rich soybean or sunflower meals result in diets excessive in overall protein. This stresses the birds and leads to more nitrogen excretion in manure and urine.

Generally, certifiers do not permit forced molting because it is very stressful to the birds. Organic producers, especially small producers, may let the flock molt naturally, though it is common to destroy/process the flock at about 70 weeks. Natural molting is not as efficient as forced molting, but it maintains the birds' welfare and extends their productive life. Ideally, layers should be allowed to molt naturally and kept for at least two to three years.

Disease and pest management. Disease prevention in organic systems starts with clean birds. Make certain to get birds from breeding flocks approved by the USDA National Poultry Improvement Program, which certifies that flocks are free of certain diseases.

Proactive health management is very important in organic production. This includes proper nutrition, and adequate housing, space and ventilation to reduce stress and support immunity.

Good sanitation is vital. Sanitation between flocks is particularly important. An 'all-in, all-out' management (completely harvesting a flock before starting a new one) is advised. This reduces pathogens, many of which die during the 'downtime'. Downtime should last two to four weeks for good control.

Thorough cleaning is an important first step towards effective sanitation and disinfection of a poultry house. Organic matter must be removed in order for a disinfectant to work. Approved sanitizers and disinfectants include chlorine materials, iodine, hydrogen peroxide, peracetic acid, phosphoric acid, organic acids and alcohol although alcohol is not particularly effective. Propane-fueled heat tools may also be used for disinfection.

In addition, water lines need regular care. They can be flushed with organic acids, such as citric acid or vinegar, to loosen debris, and then sanitised with iodine or hydrogen peroxide, between flocks. Chlorine is also used for water-line sanitation when birds are in the house.

Vaccines are allowed in organic production. Poultry vaccines are commonly used to prevent Marek's disease, Newcastle disease, infectious bronchitis and coccidiosis.

Good biosecurity should be practised, including limiting visitor access to the bird area. Footbaths with approved disinfectants, such as iodine, as well as disposable booties or dedicated footwear, can be used at the entrance to houses. Since wild birds, particularly waterfowl, can carry diseases that harm domestic poultry, it is important to exclude them from free-range areas. Outdoor feeders should not attract wild birds. Self-feeders that dispense feed on demand are advisable (see list of Table Egg Resources).

Some producers have biosecurity concerns with outdoor access and argue that vaccines need time to create immunity; however, long periods are not required. Immunity generally develops a week or so after the first boost. The last round of vaccines (usually 16-18 weeks) is intended to protect the flock during lay and outdoor access is not likely to interfere. For further information, see Table Egg Resources.

Probiotics are often used in organic poultry production to replace prohibited antibiotic growth promoters (AGP). Probiotics are beneficial microbes, which are fed to birds to establish beneficial gut microflora, thereby reducing colonization by pathogenic organisms, such as Salmonella and E. coli, by 'competitive exclusion'.

Other natural products include prebiotics, which are non-digestible food ingredients that benefit the host by selectively stimulating the growth of bacterial species present in the gut. An example is lactose, which is used by beneficial lactic acid bacteria in the gut.

External parasites such as mites can be managed by allowing birds to dust-bathe. Many producers add diatomaceous earth to the dust-baths to increase their effectiveness. If mite treatment is needed, pyrethrum is an allowed natural product. For roost mites, which inhabit roosts, cracks, and crevices in the house, a natural oil, such as linseed oil, can be used.

Rotating yards, range, and pasture is the key to reducing internal parasites. The National Organic Standard prohibits standard synthetic parasiticides, though non-synthetic materials and additions to the National List might be made. Conventional anticoccidial medications are not allowed for control of the protozoan parasite coccidiosis, which is usually controlled through management or vaccines. Read ATTRA's Poultry Parasite Management for Natural and Organic Production: Coccidiosis.

For rodent, fly, and other pest control, a multilevel approach is used, beginning with prevention and sanitation. Secondly, mechanical and physical controls such as traps and fans are used. Thirdly, natural and/or allowed synthetic pesticides can be used.

Physical alterations. Physical alterations are allowed only if essential for animal welfare and done in a manner that minimizes pain. Beak trimming (to reduce feather pecking) is controversial. Feather pecking is an indicator of stress in the perpetrator and the victim and might better be addressed through management or lower bird populations. Beak trimming is only permitted if such methods fail.

Manure management. The National Organic Standard requires managing waste in ways that do not pollute or contaminate organic products, and that optimize nutrient recycling. Burning may not be used as a means of disposal. Ideally, organic poultry manure will be returned to organic cropland and pasture. Read ATTRA's Manures for Organic Crop Production.

Organic processing issues

Wet cleaning. If detergents or other additives are used for wet cleaning, they must either be non-synthetic or among the allowed synthetics on the National List at §205.603 of the National Organic Standard. Allowed synthetics include chlorine, hydrogen peroxide, ozone and peracetic acid. These serve mostly as sanitisers rather than as washing agents. At the time of this writing, the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) lists one brand name product as an allowed egg wash.

Be conscious of where wash water goes. Ongoing and excessive use of detergent can be harmful to septic systems. Vinegar is non-synthetic and effective at removing bacteria and stains if mixed 1:3 with water. Vinegar contains acetic acid, which helps to kill microbes.

Labelling

The federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sets the basic requirements for food product labelling. There are often state-based programs available through departments of agriculture that can assist in complying with federal requirements for weights and measures and other areas of compliance.

State departments of agriculture may also have additional labelling programs that can help distinguish products. The Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food, and Forestry, for example, has a program titled Made In Oklahoma that allows in-state farms and other businesses to promote and label their products accordingly.

National Organic Program (NOP) labelling requirements. When dealing with whole table eggs, there are two levels of organic labelling:

- A product may be labelled as '100 per cent Organic' if it contains only 100 per cent organic agricultural ingredients. Table eggs can certainly be labelled '100 per cent Organic' if they were not washed, or were washed using water without any cleaners or sanitizers. The USDA's organic seal may be used on products labelled '100 per cent Organic'.

- A product may be labelled 'Organic' if it contains a minimum of 95 per cent organic agricultural ingredients. Certifiers may require that whole eggs washed or sanitized using any agent other than pure water be labelled 'Organic'. The USDA's organic seal may also be used on products labelled 'Organic'.

Additional specific requirements for organic labelling are addressed in Subpart D of the National Organic Standard §§205.300–311.

Additional regulatory issues

The Egg Products Inspection Act was passed in 1970 to ensure egg products are safe for human consumption. In 1972, quarterly on-site inspections of all shell egg processors became required. A producer with a flock of less than 3,000 hens is exempt from complying with the Act, although states have their own egg laws and regulation is on a state-by-state basis.

All food products manufactured for the public must be prepared in an approved licensed facility. In most states, licensing is overseen by the state health department. Additional approval and licensing by the state department of agriculture might also be required for some enterprises in some states. If the farm falls within the limits of a city, there may be additional zoning requirements to meet. City and/or county regulations may also apply to the construction of new facilities if those are needed.

References

6. Thornberry, Fred D. 1997. The Small Laying Flock. PS5.250. Texas Agricultural Extension Service, College Station, TX. 4pp

7. Clauer, Philip J. No date. Management Requirements for Laying Flocks. Small Flock Factsheet No. 3. Virginia Cooperative Extension, Blacksburg, VA. 2pp

8. Thornberry, Fred D. 1997. The Small Laying Flock. PS5.250. Texas Agricultural Extension Service, College Station, TX. 4pp

9. Shady Lane Poultry Farm and Poultryman's Supply Co. No date. Small Scale Table Egg Quality and Processing.

10. Anon. 2007. Sale of Shell Eggs to Grocery Stores and Restaurants. Minnesota Department of Agriculture.

11. Anon. No date. Eggs. Food Dictionary, Epicurious web site.

12. USDAD FSIS. 2007a. Focus on Shell Eggs.

Further Reading

| - | You can view the full report, including additional resources, by clicking here. |

July 2009