Improving Rapid Detection Methods for Foodborne Pathogens

Researchers at Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) have developed a microfluidic device that exploits cell movement to separate live and dead bacteria during food processing.The food processing industry is interested in technologies or methods that can quickly and accurately detect viable (live) bacteria, as these are the pathogens that can cause illness.

Common foodborne pathogen screening methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) use DNA-based methods to perform the detection. However, because both viable (live) and non-viable (dead) bacteria contain the same DNA and other properties, it is difficult to distinguish between them without performing additional time-consuming incubation and culturing steps.

In response, researchers at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) have developed a microfluidic device that exploits cell movement to separate live cells from dead ones for real-time pathogen detection.

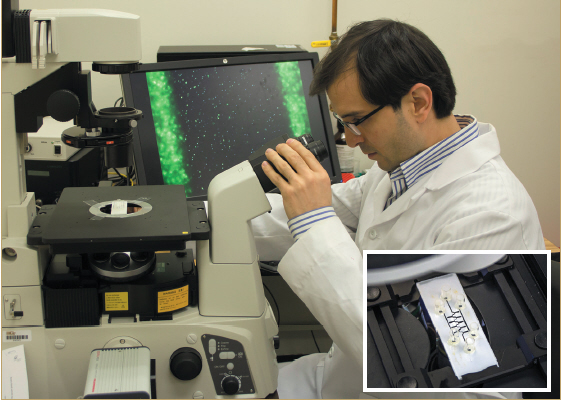

The inset photo shows a close-up view of GTRI’s microfluidic device, which exploits cell movement to separate live and dead bacteria for rapid pathogen detection.

The phenomenon known as chemotaxis is the movement of an organism in response to a chemical stimulus. For example, live bacteria naturally sense nutrient molecules such as sugars and amino acids and move toward them.

Dr Jie Xu, GTRI research scientist and project director, explained: "The hypothesis is that by changing the local environment of the cells, their movement can be manipulated so all the viable cells can be separated and concentrated. This would improve the probability of detection and also provide a high level of confidence that viable cells are being detected."

GTRI’s chemotaxis-based microfluidic device consists of a 100-micrometre thick nitrocellulose membrane layer engraved with a micron-sized centre channel to contain the bacteria-laden sample.

Two additional side channels are engraved into the same membrane layer that contains nanometer-sized pores that allow the formation of a chemical gradient across the center channel.

The bacteria interact with these chemicals in the centre channel and then move based on the nature of these interactions, either toward it if it is a food source or away if it is a repellant. The separated bacteria are then collected in the channel’s respective outlets In recent experiments, E. coli 0157:H7 was used as the model bacterium, and aspartic acid (an attractant) and nickel ion (a repellent) were used as the chemotactic effectors.

Researchers found the chemical gradients inside the channel can be maintained for an extended period. They also observed the cell population shift toward the side channel with attractant when live cells flowed inside the center channel, while the dead cells remained in the primary flow stream and exited the center channel.

The team is now in the process of optimising the separation efficiency by adjusting the concentrations of the chemicals, the design of microfluidics, and the flow rate.

Alireza Mahdavifar is a micromechanical engineer and GTRI graduate research assistant who designed and fabricated the prototype.

He explained: "This innovation includes an inexpensive and scalable fabrication process and the use of disposable and bio-compatible materials that make it suitable for laboratories and field testing around the world."

Dr Xu believes successful implementation of lab-on-a-chip technology like GTRI’s microfluidic device could enable faster and more effective food safety control.

He said: “The success of this project will make rapid viable pathogen detection possible, so the intervention process can be monitored and tailored for better food safety.

“Food products could also be delivered quickly to consumers because the current holding time to obtain testing results would be virtually eliminated. The technology could also help to identify the cause of a foodborne illness outbreak quicker.”

In fact, the team’s work is already reaping recognition and results. A paper was published in the peer-reviewed Journal of the Electrochemical Society, and Dr Mahdavifar was awarded Best Presentation for the team’s poster entitled 'A Cost-Efficient Microfluidic Device for Study of Chemotaxis and Bacteria Separation Purposes', at the Society’s 224th Meeting held from 27 October to 1 November 2013, in San Francisco, California.

The team also filed a provisional patent on 28 October 2014, etitled 'Chemotaxis-based bacterial cell separation and preconcentration'.

January 2015