Economic Approach to Broiler Production

By Aviagen. Expressed in its simplest form, the profitability of broiler production is the value of the end product minus the input costs to produce that product.The end product can be live birds ex farm; eviscerated whole carcasses, portioned meat products, or value added chicken products. Value added products are subject to a set of economic dynamics that are outside the direct evaluation of margin over feed cost, and so will not be dealt with in this article.

The value of the end product will be directly affected by supply and demand in the meat industries. Generally, the return from portioned products is greater than from whole birds, but this is greatly dependant upon local market requirements.

Feed is the major component of input cost, accounting for up to 70% of the total production cost. For this reason, any review of input costs and profitability will include a review of feed costs as a primary component of the exercise. It is also essential to optimise broiler nutrition of broilers from the standpoint of both a biological performance and economics.

When faced with increases in feed ingredient prices and rising feed costs, the first instinct is often to look at ways of off-setting the financial impact of this upon the business by reducing the nutrient specification of the feed to reduce feed cost per tonne. First, it is important to evaluate the full impact of such a decision upon margin over feeding cost. The desire to minimise feed cost per tonne needs to be balanced against maintaining or maximising margin.

Cheaper feed can reduce performance

Table 1 shows the physical and financial performance of as-Hatched broilers grown to 42 days of age on two diets of different nutrient densities. The lower nutrient density has 90% of the balanced protein levels relative to the control (100%), which is the current nutrient recommendation for the line of birds used. The term 'Balanced Protein' refers to the practical application of the ideal amino acid profile to supply broilers with the correct minimum levels of essential and non-essential amino acids. These results presented are from one of our trials carried out in the second half of 2006.

| Table 1 : Influence of Balanced Protein on Broiler Performance (Ross 308 As-Hatched; Scotland 2006) Diet Specification (based on Ross Broiler Specification, 2007) |

||

| 90% | 100% | |

|---|---|---|

| Farm Performance: | ||

| Liveweight (kg) | 2.84 | 2.95 |

| Feed Conversion Ratio | 1.85 | 1.80 |

| Feed Consumed (kg) | 5.25 | 5.32 |

| Financial Perfromance(?): | ||

| Feed price/kg | 0.274 | 0.280 |

| Feed cost/bird | 1.44 | 1.49 |

| Feed cost/kg liveweight | 0.51 | 0.50 |

| Revenue/kg | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Revenue/bird | 2.27 | 2.36 |

| Margin/kg liveweight | 0.29 | 0.30 |

| Margin/bird | 0.83 | 0.87 |

| Note: Results from a trial with Ross 308 birds, as-hatched; Scotland, 2006 | ||

Although feed cost per bird was reduced with the diet lower in balanced protein, so too were farm performance and margin, expressed either per bird or kilogramme. Decreasing nutrient levels decreases feed cost but can also decrease margin. The diet of lower nutrient density was less cost-effective when expressed per kilogramme liveweight. This is very important to remember when formulating feeds to maximise margin.

Minimum cost versus maximum margin

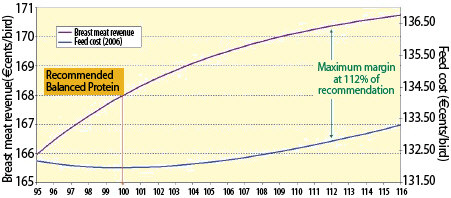

When looking to minimise feed cost, it is important to appreciate the effect on margin. Figure 1 shows that as nutrient level increases, feed cost (per bird) increases. However, due to improved bird performance the revenue from the birds also increases, and therefore margin over feeding cost is improved. The maximum margin is clearly not produced by minimising feed cost (indicated by the red circle), but is achieved at the point where the difference between revenue and cost is greatest (indicated by the green circle). The producer should aim to feed the birds to ensure margin is in the maximum margin zone illustrated in the figure. To do this, maintaining or increasing dietary nutrient density will often be justified.

Figure 1. Maximum margin is achieved where the difference between feed cost and revenue is greatest

Lowest feed cost does not produce maximum margin

It is important to make a distinction between reducing feed cost per bird and reducing feed cost per kilogram of liveweight or carcass component(s). By reducing nutrient density of the feed, the feed cost per bird will usually fall but performance may be reduced. When corrected back to equal liveweight, the move may actually result in an increased cost of production.

The level of balanced protein in the feed will have a major influence upon margin achieved and profitability. However, balanced protein is only one of the two main components of the nutritional package and energy also needs to be considered. With regard to energy sources, it has become clear that growth of the biofuels industry has resulted in feed energy prices becoming more affected by oil prices than conventional commodities markets. With an increase in the use of cereals and feed fats for the biofuels sector, combined with firm oil prices, energy is likely to become expensive. It is of key importance to appreciate that modern broilers are responsive to amino acid and energy density and that margin over feed cost must be considered when determining an appropriate feeding strategy. The next part of this article explores the optimum Balanced Protein and energy of the feed that will deliver the maximum margin over feed cost.

Balanced Protein density: an economic decision

We have evaluated response data from a number of Balanced Protein response trials and compiled biological responses for a number of traits. From this data, economic responses can be calculated for different objectives, e.g. live, eviscerated carcass and portioned products. In general, lowering Balanced Protein level reduces feed cost per tonne but also reduces performance and profitability.

Balanced Protein Level (%)

Figure 2. Relationship Between Breast Meat Revenue And Feedcosts At 2006 Prices

Balanced Protein Level (% of recommnedation)

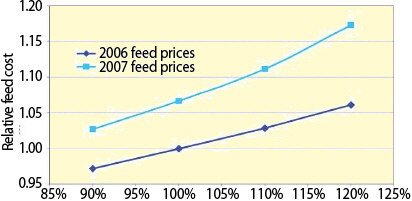

Figure 3. The Effect Of Raw Material Cost And Feed Price At Different Nutrient Densities

Balanced Protein Level (%)

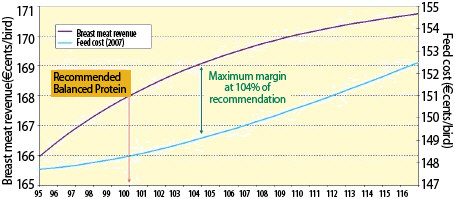

Figure 4. Relationship Between Breast Meat Revenue And Feed Costs At 2007 Prices

Feeding to optimise breast meat yield and profitability

When applying European production costs, it is apparent that feeding adequate levels of amino acids becomes even more important when profitability is linked to the production of portioned meat products.

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the impact of Balanced Protein level upon processing margin per bird. This supports the economic importance of maintaining amino acid levels at the recommendations. Furthermore, the optimum levels of amino acids and protein are above the values found in our recommendations in most situations when producing birds for yield.

Balanced Protein

The Balanced Protein Concept was developed by Aviagen as a practical application of the Ideal Amino Acid profile to supply broilers with correct minimum levels of essential and non-essential amino acids.

The Ideal Amino Acid profile applies both minimum and maximum values to the individual amino acids to produce an exact profile, which is not always achievable in commercial broiler feed formulations in practice. Balanced Protein is a practical application of the Ideal Protein idea.

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the effect of increasing feed cost upon optimal Balanced Protein level for margin. Figure 2 shows that as the Balanced Protein level increases (relative to the recommendation) bird performance improves, the yield of breast meat per bird increases and therefore revenue from breast meat increases, as shown on the 1st y-axis. On the 2nd y-axis, the increase in feed cost (per bird) resulting from increased nutrient level is shown. The optimum or maximum margin is at the point where the difference between breast meat revenue and feed cost is greatest, in this case at 112% of the recommendation.

Taking account of rising feed costs

Figure 2 shows the outcome when 2006 feed costs have been applied. In recent months, the prices of feed raw materials have increased. Figure 3 shows the interaction between raw material prices and nutrient levels of feed on the cost of finished feed. Feed cost is expressed relative to the base feed cost of 100% Balanced Protein in 2006. The cost of the feedstuffs per tonne was set at €121 for wheat, €207 for soybean meal and €490 for feed fat. These cost were increased for 2007 by 30%, 20% and 10% respectively,

As raw material price increases, feed prices increase across Balanced Protein densities. The increases are greater at higher levels of balanced protein.

As raw material prices have increased, it is necessary to revise the determination of maximum margin described previously with 2006 costs. The results of repeating the exercise with the 2007 feed costs are shown in figure 4 ;

Latest recommendation

The increase in raw material prices results in higher density feeds becoming more expensive relative to 2006 and therefore the point of optimum or maximum margin has moved downwards from 112% (in 2006) to 104% (in 2007) of the recommendation. However, it is important to note that although the point has moved down, it is still above the recommendation reaffirming the economic response of the bird to Balanced Protein.

When faced with rising feed cost, it is tempting to reduce the feed cost per tonne by reducing the nutrient levels in the diet. Lower nutrient levels will result in poorer biological performance, which may therefore reduce overall margin. The results from our internal trials, external field trials and economic analyses suggest that when faced with rising feed costs, it is important to consider reducing nutrient levels. However, the full impact upon the economics of the business should be evaluated before such action is taken.

September 2007