Spiking Mortality Syndrome in Broilers, Part 1

Although spiking mortality of broiler chickens is no longer a hot topic in the industry, it still is somewhat of a recurrent problem in several parts of the world. Angel I. Salazar brings us his empirical field observations on this malady. (Part 1 of a three part series)

Spiking mortality is referred to as a syndrome because there is no single, indisputable, consistent cause/effect relationship clearly and completely defining this malady in all its aspects.

Factors such as broiler metabolism, physiology, lighting programs, viruses, husbandry practices, feeding strategy, feed texture, house ventilation, breeder flock age and several other culprits have all been implicated at one time or another.

During the late eighties and early nineties, spiking mortality of broiler chickens was first observed in the Delmarva area of the USA. Since that time review of several sound basic management practices have reduced the incidence of this problem. To be sure, the condition still shows its ugly face with some regularity in many parts of the world. Thus, much basic, practically oriented research work still needs to be done.

One can say there are no air tight preventative or eradication measures in place. There are some treatment options that offer varying degrees of success in the field. There are only a few effective treatment options or management solutions available to handle this problem.

Signs/Symptoms

When dealing with spiking mortality, one frequently wonders, which came first? Was it the chicken or was it the egg?

Affected birds show a typical posture, lying down on their bellies on top of the litter, leaning forward with their legs extended, out stretched.

Spasms, tremors may or may not be part of the picture. If tremors are present the situation may be confused with avian encephalomyelitis.

Young broiler chickens develop hypoglycemia and become blind. It seems logical to assume once a bird is blind, it cannot get to either feed or water.

Thus, affected broilers will eventually starve, emaciate, become an outlier or, a runt and die. One would think this chain of events takes place gradually, over some time period. However, death may occur within hours after the onset of symptoms.

In short, the above chain of events may explain why quite a few of affected, dying or recently dead birds, are large, plump broilers which were in good/excellent condition and show no signs of emaciation due to long term starvation.

Upon posting affected, dying birds or “fresh” mortality is quite common to find an orange tinged fluid in lower small intestine and in the cecum. A nonspecific, mild to severe enteritis may also be observed. Also, mucus filled, foamy droppings are often seen on the litter.

Post mortem lesions may include bird dehydration particularly evident on leg shanks. Frequently, none of these lesions are evident when dealing/posting freshly dead, large, rapidly growing broilers quickly succumbing to the problem.

Basis for Proper Diagnosis

Basis for Proper Diagnosis

Causative/etiological agent: Viruses were suspected during the initial outbreaks of SMSC. The Delmarva Task Force reported the isolation of an avian adenovirus from flocks experiencing the syndrome. Additional studies on the role of an adenovirus were later done at the University of Georgia. The results of these experiments were not conclusive.

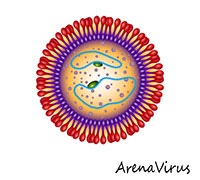

Dr. James Davis of the Georgia Poultry Laboratory, together with other US researchers, investigated the problem and found an emerging virus. This virus belonged to the arenaviridae family and was consistently isolated from the droppings of birds exhibiting spiking mortality.

Dr. Davis' work showed higher numbers of arena virus particles present in the feces of broilers, broiler breeders and commercial layers experiencing enteritis. Further, the feces of chickens exhibiting spiking mortality have been found to contain particularly high numbers of arena virus particles. Since then, Dr. Davis and others conducted a number of different experiments and reproduced the syndrome by administering the arena virus to normal birds.

Dr. Davis' research indicated that shortly after infection by the arena virus in question, a short period of starvation for the chicken is enough to elicit the syndrome. Thus, it may take more than just a viral infection to bring about the syndrome in broilers.

Particularly, one should give due consideration to other stress factors like periods of poor or marginal feed availability, bird panting and or heat exhaustion during extreme hot weather.

Arena viruses infect areas of the brain which regulate hormone levels in the body, particularly growth hormone. Mice infected with the arena virus have been found deficient in growth hormone which results in hypoglycemia and in growth depression.

Since arena viruses are also known to infect beetles, mice, rats, other birds such as pigeons, a concerted effort is needed to keep all these pests under control.

Presumptive diagnosis of the problem can be based on the specific timing of field observations. The most usual time window for the occurrence of the problem in broiler flocks is from 8 to 18-20 days of age. The condition typically shows up at the beginning of the second and toward the end of the third week of grow out but it can happen as late as 30 - 35 days of age.

Also, there is a sudden onset of the condition and it shows a typical mortality pattern. Initially, only a few affected birds are detected in the field. Then, quite often, from one day to another, morbidity and mortality rise dramatically.

A loud chirping of a few birds is sometimes an early warning sign we are possibly heading for trouble. Too often, birds seem to be thriving. Then, a sudden and unexpected jump in mortality takes place from 8 to 14 days of age. The increased mortality lasts for several days, after which, mortality usually returns to a relatively normal level.

Some producers feel the fast growing male broilers in the flock are more severely affected than their female counterparts.

Most troublesome is the fact that affected birds that survive an outbreak never achieve the level of performance of unaffected birds. This situation increases the percentage of birds that must be culled following an outbreak.

Treatment Drug Options

Sometimes in the face of an outbreak of spiking mortality field veterinarians report some benefit from a timely and prompt administration of a quinolone antibiotic via the drinking water. This is difficult to assess since viruses are not affected by antibiotic administration. Is the antibiotic preventing opportunistic bacteria from further complicating the situation?

Glucose or sugar supplementation in the drinking water has also been tried. The goal is to achieve a 2 per cent concentration in the drinking water via a stock solution utilizing a proportioner or a medicator. The treatment is done for one or two days. The question is, should this be a routine practice in troublesome farms?

July 2015