Avian Pneumovirus review: What do we know so far?

Avian pneumovirus or avian metapneumovirus (aMPV) is a respiratory disease that causes infectious turkey rhinotracheitis (TRT) and Swollen Head Syndrome (SHS) in broiler chickens, layers and breeders.It first appeared in 1978 in South Africa and is currently a disease reported and subjected to control programmes almost everywhere in the world.

Natural reservoirs are turkeys, broilers and chickens, although it should also be noted that wild or domestic birds can also be reservoirs. The virus has been detected in the ciliary epithelium of the respiratory system and the oviduct.

It is transmitted by direct contact between infected birds and sensitive birds. Transmission is also possible by indirect contact including exposure to aerosol droplets and contaminated farm material (boots, clothing and equipment).

With this article we want to try to resolve typical concerns and frequent questions about the different strategies for prevention, application of the vaccine and evaluation of the disease.

Can vaccination against aPMV be carried out jointly with vaccination against other respiratory diseases?

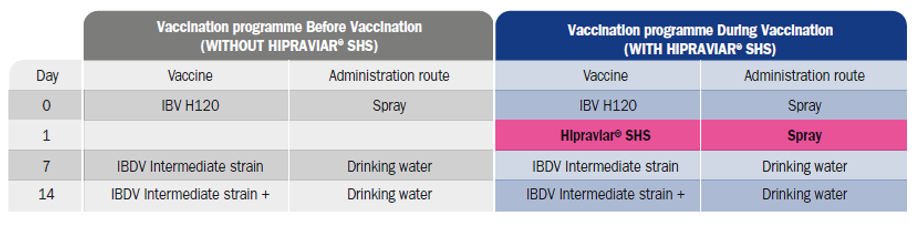

The need to reduce the number of days on which vaccination is carried out in broiler flocks has led to the proposal that studies should be conducted to determine whether joint administration of a vaccine for the prevention of avian pneumovirus and other types of respiratory vaccines is possible. Up to now, these vaccines have been administered separately in order to minimize interactions between them. In principle, the fact that they all compete for the same receptors would imply that there would be interaction between them, and, ultimately, the protection afforded against pneumovirus could be affected.

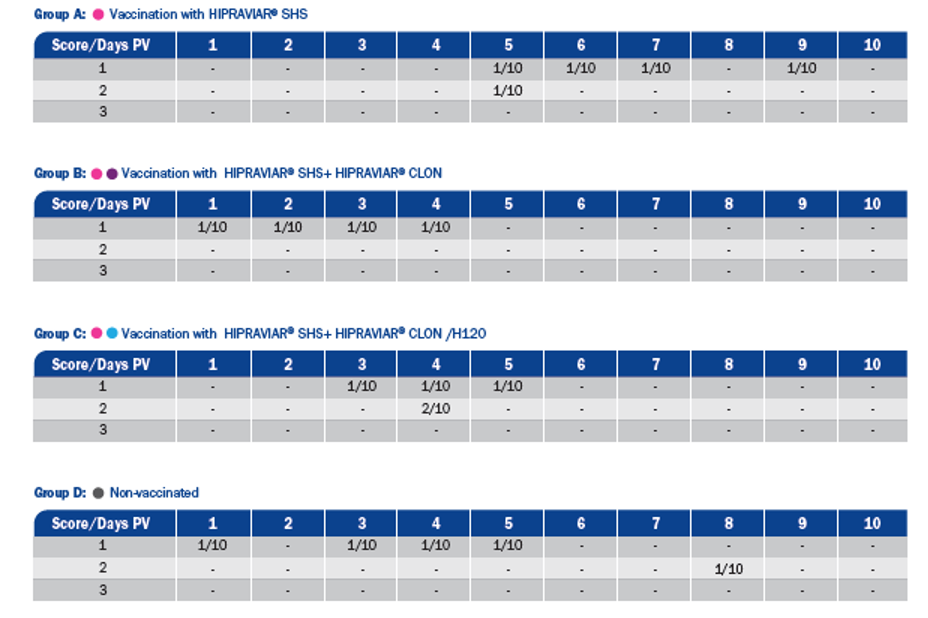

In a trial conducted by HIPRA, the birds were observed daily for 10 consecutive days after vaccination to determine the presence of clinical signs attributable to the joint administration of the vaccines.

The following evaluation criteria were used to assess the presence of vaccine reactions:

1. Presence of mild clinical signs (watering eyes).

2. Presence of moderate clinical signs (respiratory symptoms with coughing, panting, etc.).

3. Presence of severe clinical signs (severe respiratory symptoms and depression).

Vaccinated birds showed no obvious clinical signs attributable to joint vaccination. This indicates that combined vaccination with different products did not produce any post-vaccination reactions under the experimental conditions. Complete protection against the challenges for each group after administration of different combinations of vaccines was observed in our experiment.

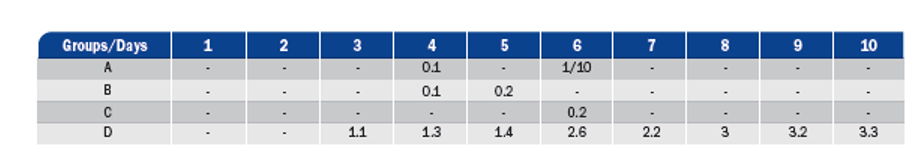

Assessment of the challenge against avian pneumovirus:

The following criteria were used to assess the clinical signs from the challenge with avian pneumovirus:

1. Little nasal discharge

2. Moderate nasal discharge

3. Abundant nasal discharge

4. Turbid nasal discharge

5. Ocular discharge

6. Swollen sinus

7. Mortality

The vaccinated groups showed few symptoms whereas various levels of nasal discharge, ranging from level 1 to level 3 were observed in the control group. Mortality was not recorded in any case.

This study provides a first approach to the safety and efficacy of the combination of respiratory vaccines.

How can we evaluate the disease in order to determine the efficacy of vaccination?

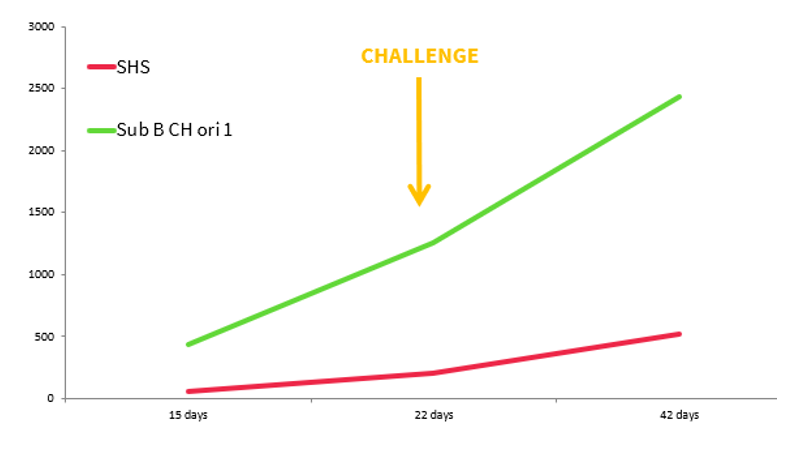

A study was conducted at Hipra in order to determine the behaviour of two different live attenuated vaccines against aMPV in relation to IgG production, measurable using the CIVTEST TRT ELISA kit, before and after challenge.

For this, there were 3 groups of SPF birds vaccinated with 2 different live attenuated vaccines, Subtype B Chicken origin, and one group not vaccinated:

SHS- |

0 days, eye drop |

Sub B CH ori 1- |

0 days, eye drop |

Control not vaccinated- |

0 days, eye drop |

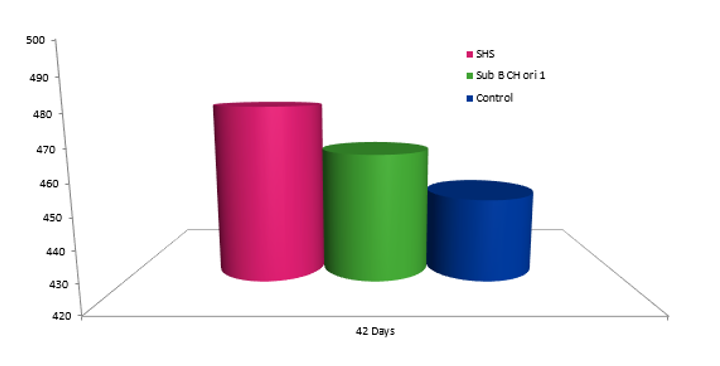

These groups were challenged at 22 days of age to check vaccine behaviour (Ig G response). The serology and weight show that the level of IgG production induced by live aMPV vaccines is not a good indicator of the degree of protection, although they may be useful for differentiating between flocks in which high pressure from the field virus persists (with high levels of seroconversion) and flocks in which the vaccine is displacing the field virus. This affects the performance of the animals, which is why the weight of the HIPRAVIAR® SHS group is better that the others.

Can broilers be affected by this disease? How can we prevent it?

Yes, they can! Here you have the results of a field case, where the problem showed itself as a respiratory disease that affected the upper respiratory tract between 28 and 35 days of age, with bacterial complications and weakening and mortality associated with secondary bacterial infection. Antibiotic treatments were administered, with good efficacy during treatment, but with rapid recurrence of bacterial infection after treatment.

The whole comparative study was carried out on the same farm, in successive batches, over a total period of 8 months (4 batches, 2 without vaccination against aMPV and 2 vaccinated). The farm comprises six sheds, with a capacity of 240,000 birds per cycle. A total of 917,000 birds was evaluated.

The incorporation of vaccines against aMPV into a vaccination programme should always be based on a reliable diagnosis of the agent causing the health problems, with clinical, serological and, if possible, molecular data.

The use of an attenuated live vaccine, subtype B, chicken origin (HIPRAVIAR® SHS) on this broiler farm affected by aMPV leads to an improvement in the health status of the batches with significant positive repercussions on the zootechnical results and so an improvement in the economic results.

In any case, poultry vaccination programmes against aMPV should be assessed individually in each farm and season of the year, making the monitoring of the flocks at the marketing age very important to plan an effective vaccination programme.

Which vaccination programme is most effective when live vaccines are not allowed?

In Colombia, where live vaccines against avian pneumovirus cannot be used, the strategy to control the disease is different.

Inactivated vaccines are very important for long cycle birds and their main function is to reduce the excretion of field viruses in case of infection and to prevent their replication in the reproductive tract in order to protect the quality and quantity of eggs.

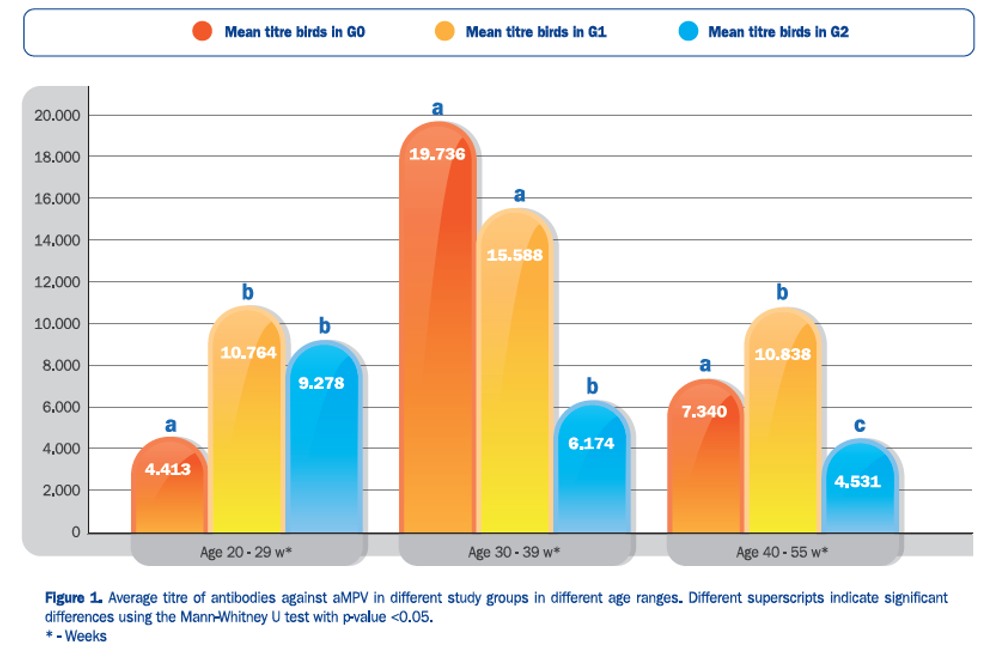

Hipra carried out a study in Colombia to understand the existence of significant differences in levels of antibodies to the disease caused by aMPV between unvaccinated batches (G0), batches vaccinated with an inactivated vaccine dose (G1) and batches vaccinated with two doses of inactivated vaccine (G2) as recommended in countries where the use of live vaccines is not permitted.

We can conclude that in countries where live vaccines against aMPV cannot be used, the serological behaviour against aMPV of birds vaccinated with 2 doses of HIPRAVIAR® TRT / AVISAN® TRT (G2) is more predictable and less conditioned by the field challenge than in unvaccinated birds (G0) or in single-dose vaccinated birds (G1).

Conclusions

Measures to treat aMPV are very expensive, as antibiotic use increases and investments in farm management and biosecurity measures are also costly. Therefore, a good vaccination plan is the best way to keep our animals safe.

Having a good health programme in our operation not only prevents disease, but also reduces production costs, thus improving the quality of the final product and the animals’ performance.

Hipra has all the necessary tools to diagnose and control the aMPV, thus helping poultry companies to achieve good results, rationing the consumption of antibiotics that today is demanded by the market and public opinion.

| References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathi H., Villa J., Rubio J., (2015). Study of the joint administration of Hipraviar® SHS with respiratory vaccines for preventing newcastle disease and infectious bronchitis. World Veterinary Poultry Association, Cape Town, South Africa. | ||||

| Corella J.S., Rubio J., Perozo E., (2015). Evaluation of serological response (IgG) following avian Metapneumovirus vaccination and challenge. World Veterinary Poultry Association, Cape Town, South Africa. | ||||

| Corella J.S., Balestrin G.A., Ferreira da Silva V., (2014). Experience of the use in broiler chickens of a live attenuated vaccine subtype B, chicken origin, strain 1062, against avian Metapneumovirus. 4th International Veterinary Poultry Congress and Exhibition of Iran. | ||||

| Corella J.S., Grillo D., Blanch M., (2017). Comparison of serological results of 3 different vaccinal programs with inactivated vaccine against avian metapneumovirus (aMPV) in Colombia. XXV Congreso Latinoamericano de Avicultura. Guadalajara, México. | ||||

| Buys, S.B., DU Preez J. H., (1980). A preliminary report on the isolation of a virus causing sinusitis in turkeys in South Africa and attempts to attenuate the virus. Turkeys. 28, 36. | ||||

| Cook J.K.A., Cavanagh D., (2002). Detection and differentiation of avian pneumoviruses (metapneumoviruses), Avian Pathology, 31:2, 117-132. | ||||

| LI., J., Cook J.K.A., Brown T.D.K., Shaw K., Cavanagh D., (1993). Detection of turkey rhinotracheitis virus in turkeys using the polymerase chain reaction. Avian Pathology. 22, 771-783. | ||||