Bobwhite Quail Production 1

Advice on the production of bobwhite quail from Professor Peter A. Skewes of Clemson University and Professor Emeritus Henry R. Wilson of the University of Florida; Florida Cooperative Extension Service. This article offers general advice and information on the management of breeders.Foreward

The sudden explosion of a bobwhite covey rising from the ground cover produces an exciting thrill, especially for a quail hunter. But because of extensive land development, there has been a reduction in the amount of habitat available for quail hunting. As a result, the number of hunting preserves in many states has grown rapidly in recent years. The use of quail as a food source, both for home and in many dining establishments, also continues to increase. To satisfy this growing demand, the production of game birds such as bobwhite quail has become a multi-million dollar industry.

This publication was developed to assist the seasoned quail producer, as well as to provide a sound base for the novice. It should provide basic information needed in the production of quail for a hobby or for business.

Getting Started

Management

In the poultry business, management abilities and practices determine the difference between success and failure. Management problems are far easier and cheaper to prevent than to solve, and the limited availability of effective disease treatments makes proper management an absolute necessity.

It has been estimated that 80 per cent of all health problems encountered by quail producers could have been prevented by close attention to sound management principles and details. Inexperienced growers should start with small numbers of birds, increasing flock size as experience is gained.

Remember that bobwhite quail are living creatures that are totally dependent on their caretaker for their well-being. If you cannot give the necessary attention and care to the quail, then the quail will suffer, the business will suffer, and you will suffer. Total commitment is the only way to success!

Marketing

Marketing possibilities, probabilities and plans should be determined before starting any new business venture. Many producers contract their production of birds and/or eggs for one to two years in advance. To be successful in marketing, you must produce a high quality product that consistently meets or exceeds the customer's needs. Repeat business and word-of-mouth advertising are the quail producer's best partners.

Laws and regulations

In most US states, there are rules, regulations and laws applicable to confinement rearing of game birds. A licence or permit is usually required to keep quail in confinement, to exhibit them to the public or to operate a hunting preserve. For information, contact your local conservation officer or your state wildlife department. This information should be obtained before purchasing birds or eggs.

Any time quail are transported across state lines, they must be accompanied by a health certificate from a veterinarian. Contact the State Veterinarian in the state of destination for specific details.

Assistance

Assistance in game bird production is available from several sources, as listed in Table 1. Your local county extension agent or soil conservation service agent can be an invaluable source of information. State extension specialists and state diagnostic laboratories should also be contacted for assistance. State, regional, and national game bird organisations usually offer conferences and publications that are useful.

| Agency or Organization | Type of Assistance |

|---|---|

| State Diagnostic Lab | Game bird health problems, management problems |

| State Cooperative Extension Service sources | General information, quail literature, management advice |

| State Fisheries and Wildlife Department | Permits and licensing for rearing and marketing quail; laws and regulations |

| Local Natural Resource Conservation Service | Assistance with land and natural resource management |

| Local Agricultural Stabilization Conservation Service (ASCS) |

Information regarding payments for wildlife conservation or release |

| North American Game Bird Assoc., Inc. Dr Gary Davis - North Carolina State University |

Information and assistance from national level, promoting the game bird industry to the public |

| Southeastern Game Bird Breeders and Hunting Preserve Association (Contact North American Game Bird Association for address of current president.) |

Marketing, contact with breeders and producers, advertisement, informative meetings |

| *The agencies and organizations listed here may provide additional assistance. Contact your county office of the Cooperative Extension Service for the addresses of the agencies in your area. | |

Breeders

Stocks

There are several subspecies of bobwhite quail. The eastern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus virginianus) is the most common, both in the wild and in captivity. The eastern bobwhite has been reported to be larger in the northern states than in the southern states (6.9 versus 5.9 ounces).

Four other subspecies are generally recognised: plains bobwhite, masked bobwhite, Texas bobwhite and Florida bobwhite. Many of the domestically grown stocks have been selected to some degree for size, appearance, egg production and hatchability. Several varieties are larger than those found in the wild.

Selection of breeder stock

The type of quail selected will depend to some extent upon the use that will be made of the birds. The larger varieties should be used when growing birds for meat purposes. These varieties are also better suited for home use and hobbyists because they tend to be more docile. The larger varieties usually lay fewer eggs than the small varieties. The small and moderate sized varieties (six to seven ounces; 170 to 200g) generally are desired when growing birds for hunting preserves because they usually fly better and faster than the larger birds.

The following points should be considered when purchasing hatching eggs or birds:

- Obtain eggs or birds from producers with a good reputation.

- Select stocks with a history of good egg production, hatchability and livability.

- Hatching eggs should be uniform in size. Remove very large and very small eggs. Eggs should be clean, free from odd shapes and have a smooth shell without cracks or thin places. Check length and conditions of storage.

- Newly hatched chicks should be alert, active, vigorous and free from abnormalities. Cull all weak, small, inactive chicks and those with curled toes or "spraddled" legs.

- Check birds (and parents if possible) for uniformity in size, color and shape; check for abnormalities, injuries and feathering.

- The birds should be free of disease. Check for past history of disease or mortality.

- Select stock that has been blood tested for pullorum and typhoid and found to be clean.

- Always start more birds than needed so that required culling can be done before final selection.

Future breeder stock

During the first season of egg production, it will be necessary to begin planning for the next season. Your breeders can be used again for two to three additional seasons. It should be noted, however, that each recycling of the breeders will result in lower egg production, lower fertility, lower hatchability, poorer chick quality, disease build-up and an increased breeder mortality rate.

Close observation and culling should be carried out throughout each laying season. The breeders must be rested for a minimum of three months between each breeding season. Rest the birds by turning off the lights and providing a maintenance-level diet.

An alternative to recycling your breeder stock is to replace it with offspring from your current breeders. This will be the desired system for most producers. If genetic selection is to be practiced, this system will permit more rapid improvement of the stock. Use birds from hatches before the peak production period. These birds are usually stronger, healthier, more disease-resistant and lay more eggs. In large breeder flocks, this type of selection and breeder replacement will not create any inbreeding problems. Small breeding operations (less than 200 pairs) will need to introduce unrelated breeder stock at least every third year.

It is possible to improve egg production in breeder stock without the necessity of pedigree production records. This is done by hatching succeeding generations from eggs laid at five to six months of production. In this way, breeder chicks are hatched from the old breeders that continue to lay well over a long production period. This is most successful with larger flocks that do not need periodic introduction of new stock.

The best way to introduce new breeder stock is by purchasing hatching eggs. If eggs are not available, day-old chicks can be purchased for future breeding stock.

Only as a last resort should adult breeders ever be brought into an existing operation. The risk of introducing disease problems far outweighs any benefits that may be derived from the new blood lines. Any birds other than newly hatched chicks should be quarantined for at least three weeks to ensure the absence of disease. Whenever possible, purchase eggs or stock from dealers participating in the National Poultry Improvement Plan.

Breeding systems

There are three options available for housing breeders: floor pens, colony cages, or individual cages.

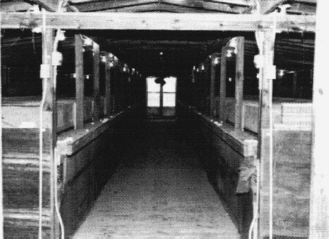

Floor pens (Figure 1) are the least expensive and least desirable way to maintain breeders. The major disadvantages of floor systems are increased fighting, dirty eggs, an inability to identify non-productive birds and greater exposure to disease-causing parasites. Even with excellent sanitation and management, floor breeders will not produce as well as caged breeders. On the other hand, floor pen breeding allows more margin for error in feeding and watering because the birds can move from one feeder or waterer to another.

Each pen has dividers every four feet to reduce piling

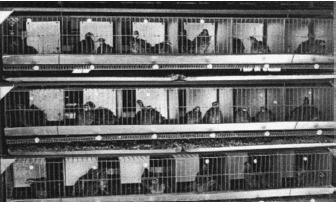

Placing breeders in cages with wire flooring greatly decreases the exposure to disease and produces clean eggs that are very easy to collect (Figure 2). The cage system can be used for colony cages that house several females and males or for individual cages that house a single breeder pair. Colony cages are designed to hold a large number of breeders at male:female ratios ranging from 1:1 to 1:4. Although the front width is not important, the cages should not be any deeper (front to back) than three to four feet. This will permit easy removal of dead or cull birds and proper cleaning and disinfection. The cages should also have solid dividers (partial) every three to four feet to prevent the birds from piling in one end of the cage and to discourage cocks from fighting.

of breeding stock but requires additional cage space

Individually pairing breeders makes possible the culling of unproductive or infertile birds and generally results in less fighting, mortality and egg breakage. Individual pairs are also necessary if you practice genetic selection involving pedigree records. This system is most expensive in that greater numbers of males are used, resulting in greater feed consumption and space requirements.

A male to female ratio of 1:1 produces the highest egg production, fertility, and hatchability, regardless of the system. Ratios of 1:2 or 1:3 will result in a lower number of chicks per hen but will produce a greater number of chicks per breeder (counting males and females).

Breeder Environment

Four major environmental factors that affect breeders are light, temperature, air quality and space.

Light stimulates the breeder's reproductive system which, in turn, initiates breeding. Under natural conditions, quail begin to mate in the spring in response to the increasing day length. By providing artificial light, you can bring the breeders into egg production at any time and maintain production throughout the year, regardless of the natural day length.

Artificial lighting should provide 17 hours of light per day. More than 17 hours per day is unnecessary. If you are using a 17-hour day length and your birds are exposed to natural daylight, this will mean more hours of artificial light when the days are short and less when the days are long. One of the best light-control systems uses a time clock to turn the lights on in the morning and off at night, with an electric eye to turn the lights off at dawn and on at dusk within the schedule of the time clock setting.

The light intensity should be approximately five foot-candles. This can be obtained by using 60-watt incandescent lights at 10-foot intervals. Never reduce the length or intensity of the light because this will result in a reduction or cessation of egg production.

In response to stimulatory light, some hens will begin egg production as early as 16 weeks of age but most will begin production between 22 to 25 weeks of age. The eggs should reach settable size within two to three weeks. If the birds are older and larger when egg production begins, the initial egg size is larger and fewer difficulties (especially prolapsed oviduct or impacted eggs) are encountered. Eggs from young breeders often do not hatch well and the chicks have higher mortality. Near the end of the laying cycle, hatchability tends to decrease; therefore, many producers terminate production before severe declines occur.

For optimal egg production and feed efficiency, the breeders' environment needs to be maintained at a temperature between 50°F and 85°F. Lower temperatures cause an increase in feed consumption, and higher temperatures reduce egg production, fertility and hatchability. Sudden changes in temperature will also cause a decrease in production.

Air quality must be maintained by providing adequate ventilation to remove dust in the winter, heat and humidity in the summer, and ammonia at all times. Ventilation should not cause draughts on the breeders or rapid changes in the temperature. If quail are kept on wire floors in raised pens and are exposed to the cold, drop curtains should be provided to prevent winter winds from circulating beneath the birds. Over-winter the breeders in pens of 20 or more birds to help provide adequate warmth.

While one square foot per bird should be allowed for birds in floor pens, half a square foot per bird is adequate for those in individual or colony cages. Breeders should be provided with a minimum of one linear inch of feeder space and one-third of a linear inch of waterer space per bird.

Breeder Timetable

The entire breeder schedule is developed in reverse from the date that eggs from the breeders are needed.

- Brood the breeders as described under 'Brooding' (in the next part of this article).

- Have the breeders tested for pullorum-typhoid disease. To reduce stress on the birds, the testing should be done before egg production begins. You can get a list of approved blood-testing agents from your local county agent or the Poultry Improvement Association in your state.

- Pair the breeders four to six weeks before the natural laying season or at least two weeks before lights are provided. Natural laying seasons vary for different geographical areas but the local wildlife conservation officer can provide the approximate times.

- Move breeders to breeding facilities: floor pens, colony cages or individual breeder cages.

- Beak-trim the breeders at hatch and, if necessary, before mating (see 'Cannibalism' in the next part of this article).

- Plan to increase artificial lighting one hour per week so that a 17-hour day length will be reached between 24 to 26 weeks of age.

- Switch from grower feed to breeder feed two to three weeks before anticipated egg production or no later than when five per cent production is reached.

- When egg production drops below acceptable levels, end the breeding season by decreasing the lighting and returning to a low-level grower or maintenance diet. Following a three-month rest, the breeders can be used again.

It is advantageous to keep individual records on breeders, so that those birds beginning egg production very late, laying at a low rate or having low hatchability can be culled early in the laying cycle.

Egg production for a six-month breeding season should average above 50 per cent, or more than 90 eggs per hen. This will vary with strain of bird, lighting programme and other management factors. The best hens in the flock can produce 160 eggs during the six-month season. When breeders are maintained under proper conditions for a full year, the average egg production will be from 150 to 200 eggs per hen.

This publication was first published in 2003. Further information from it will be provided next week.

December 2014