Bobwhite Quail Production 4

Advice on the production of bobwhite quail from Professor Peter A. Skewes of Clemson University and Professor Emeritus Henry R. Wilson of the University of Florida; Florida Cooperative Extension Service. This article offers information on diseases, handling and release of quail and processing of the meat and eggs.Disease Prevention

Any time birds are removed from their natural habitat and raised in confinement, the chance of disease becoming established in the population is greatly increased. Since treatment of a specific disease is not always effective, preventing disease is far more economical than curing it. Because quail seem to be even more sensitive to mismanagement than domestic fowl, good management practices are vitally important in preventing and controlling disease. Regular, close supervision and the ability to recognise disease problems early are both essential. The diagnosis must be verified before the disease is treated. Seek outside help from avian veterinarians in the state diagnostic laboratories when needed. Many of the common poultry diseases can be prevented and/or controlled by observing the following practices.

Use only clean, disinfected crates or boxes to transfer the birds. Quarantine any new stock for a minimum of three weeks to reduce the chance of introducing disease into your existing stock. Isolate young stock from adult breeders. Young stock is more susceptible to disease organisms, and may become infected from adult birds. Never add new adult breeding stock to your flock. Do not exhibit birds at fairs or shows and then return them to your facilities. If they must be returned, isolate them for at least three weeks.

Sanitation is a must in any good management programme. Start with clean, disinfected pens and equipment, and be sure you clean the premises thoroughly and often. Any new equipment or materials should be cleaned and disinfected before being brought onto the farm. Most of the common poultry diseases are caused by organisms that the birds pick up from the ground or from contaminated droppings.

Care for the youngest birds first and the oldest birds last; care for healthy birds first and sick birds last. Quail exhibiting signs of disease should be provided with heat in a dry, draft-free location. Always isolate known infected stock from the rest of the flock. Remove individual sick and dead birds from the pens daily. Incinerate, bury or dispose of dead birds properly. In some cases, it may be necessary to depopulate the entire farm and thoroughly disinfect the houses, equipment and surroundings. After working with diseased birds, shower and change clothes and shoes before visiting other birds.

Controlling traffic in and out of the facilities is vital to the success of your sanitation programme. Do not allow your workers to raise any poultry of their own or to visit other poultry or game bird farms. Visitors should be kept out of the pens and breeder areas. If visitors must enter the facility, insist that they wear protective clothing and plastic boots. The premises should always be locked to prevent unauthorised visitation in your absence. Control rodents, wild birds, flies and other insects, as they can be carriers of disease organisms and external parasites. Do not keep other species of birds on the premises.

Treat with drugs only when necessary and with proper dosage and precautions; drugs are expensive and can be harmful if misused. Mismanagement is probably the most common contributing factor to disease problems. There are no drugs or medications for the prevention and cure of mismanagement. Good records and close observation of the birds will provide an early warning of management problems or disease and are often a valuable diagnostic aid.

Diseases

Without training, equipment and experience, the average game bird manager cannot read about a disease or look at a picture and then make a diagnosis in the field. Properly equipped and experienced avian veterinarians will be of invaluable assistance. The diagnosis and treatment of disease should be left up to professionals. Please contact your state diagnostic laboratory as soon as you suspect a problem.

The following are some of the more common disease and parasite problems that are encountered. The specific disease information listed here is for reference only. Treatments should be administered under the guidance of a veterinarian.

Ulcerative Enteritis (Quail Disease)

This is a highly contagious disease that usually causes high morbidity and mortality. It is the most common and destructive disease of quail, and losses may reach 100 percent if not controlled. It is caused by an anaerobic bacterium (primarily Clostridium colinum) found in the intestinal tract. The organisms are transmitted by the ingestion of contaminated droppings, feed or water.

Ulcerative enteritis may appear rapidly, causing high mortality within two or three days following the onset of clinical signs (5 to 14 days after infection). Many of the dying birds will be well fleshed, with feed in the crop. Birds that survive for several days or weeks will sit or stand humped-up, having eyes partly closed, ruffled feathers, watery droppings and weight loss. Internal lesions are seen as small haemorrhages in the inner wall of the lower intestine and caeca, which coalesce and become larger, yellowish ulcerations. The liver may also contain yellow or gray spots and the spleen may become enlarged with haemorrhages.

Several drugs*, including Lincomycin, Streptomycin, Neomycin, Erythromycin and Virginiamycin, have been shown to aid in controlling the disease. (*The use of trade names in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information. UF/IFAS does not guarantee or warranty the products named, and references to them in this publication do not signify our approval to the exclusion of other products of suitable composition.)

Recovered quail may act as carriers and should be isolated from young stock. Pens, cages and particularly ground or litter runs may remain infected over a long period of time. Proper management is the key to prevention and control.

Coccidiosis

This is a common disease in quail and is caused by protozoa that invade the walls of the intestine. Mortality and morbidity can be very high. Coccidiosis is transmitted by ingestion of droppings from infected birds. The life cycle of the organism is favoured by damp litter and warm temperature. The ingested coccidia invade the lining of the intestine, causing tissue damage, reduced nutrient absorption, and secondary infections.

Clinical signs of coccidiosis may include decreased feed and water consumption, loss of weight, huddling, droopiness, ruffled feathers, diarrhoea with a tinge of blood and mortality. The disease occurs more often in young birds. Older birds are usually more resistant to the problem, even if an immunity has not fully developed.

The incidence and severity of coccidiosis can be lessened by growing birds on wire floors. All litter and ground-reared birds are exposed to coccidiosis but will develop immunity to the problem. Whether or not the birds get sick as a result of the exposure is in direct relation to the sanitary condition of the pen. Where sanitation is excellent, exposure is not usually overwhelming, and the birds develop immunity without getting a clinical case of coccidiosis. Unsanitary conditions almost invariably result in clinical cases that must be treated. Drugs are available (Monensin) for prevention and treatment, and recovery of infected birds is relatively good with early treatment.

Quail Bronchitis

This respiratory and intestinal disease is highly contagious, having a sudden onset, rapid spread and a mortality of from 40 to 100 per cent. It is particularly a threat when quail of different ages are maintained on the same premises. Quail bronchitis is caused by a virus. It can be spread by direct contact, on airborne particles and by mechanical carriers.

Quail bronchitis most often occurs in birds under seven weeks old, and in some cases, as early as seven days old. Older birds are generally affected less severely. The characteristic findings are the sudden onset and rapid spread of tracheal rattling, wheezing, coughing, and sneezing. A nasal discharge, watery eyes, depression, huddling, ruffled feathers and a sticky diarrhea are common, with some birds showing neurological signs, especially twisting or bending of the neck.

Young birds that recover from quail bronchitis are usually immune to later exposure. They may, however, have lower egg production, fertility, and hatchability; some birds may never lay eggs.

There is no specific treatment for quail bronchitis. However, treatment with Tylan or Gallimycin may be helpful. Good management and sanitation practices should be followed to prevent the occurrence of the disease.

Avian Pox

Avian pox is a relatively slow-spreading viral infection that is transmitted primarily by mosquitoes or other biting insects. Some bird-to-bird transmission may occur through direct contact or in water and feed. Insects such as gnats or flies may spread the virus, especially when the birds' eyes are affected.

General symptoms are loss of appetite, dullness and decreased fertility. In dry pox, there are wart-like scabs and nodules on unfeathered skin and on the head. The eyes may be watery. In wet pox, there are cankers in the lining of the mouth, throat and trachea that may cause the bird to suffocate or to starve.

Mortality from pox is usually not severe, especially in the dry form. Vaccination with a quail pox (not fowl pox) vaccine at six to 10 weeks of age can prevent the cutaneous form (dry pox) and the oral and nasal forms (wet pox) of quail pox. There is no treatment for affected birds; however, an antibiotic-vitamin mix added to the water may be of some help.

Other Diseases

A variety of other diseases may occasionally be a problem. Some of these are: infectious coryza, cryptosporidiosis, aspergillosis, fowl cholera, staphylococcosis, blackhead, chronic respiratory disease (CRD), pullorum, colibacillosis and trichomoniasis.

Worms

Quail can be infected with several types of internal parasites, including large roundworms, caecal worms, capillarid worms and tapeworms. The general symptoms of worms are unthriftiness, weakness, droopiness, poor growth and, in severe cases, emaciation. The large roundworms are found in the small intestines and may measure as much as three inches in length. Consult an avian veterinarian for recommended treatments.

Caecal worms are found almost entirely in the caeca. They usually affect the bird less than most other worms but are very important in the transmission of the blackhead organism (Histomonas). Phenothiazine or Hygromix compounds are effective in controlling cecal worms.

Capillarid worms generally occur in the tissue layers in the upper part of the intestinal tract (oesophagus, proventriculus, and crop) and occasionally in the ceca. Most of these worms are very small, not easily seen by the unaided eye, and can build up on the premises rapidly. The worm eggs are picked up off the ground and out of droppings. They cause a thickening of the crop wall, resulting in high mortality. The birds give the appearance of starvation and, in the final stages, gasp as if having difficulty breathing. Some control may be achieved with Thibendazole or Tramisol compounds. Experimental drugs have shown promise against some forms of capillary worms, but no effective treatment is available at this time. Prevention is possible by use of good management and sanitation practices.

Tapeworms are flat, segmented worms that may be several inches long. There are several species, the most common of which are found in the small intestine. Intermediate hosts such as earthworms, snails, flies, etc. are necessary for tapeworms to be infective to birds. Treatment with dibutyltin dilaurate and preventing contact with intermediate hosts will help control tapeworms.

Worm populations can be effectively reduced by fumigating the soil with methyl bromide.

External Parasites

The birds should be checked regularly for signs of external parasites. Some of the more common external parasites are fleas, lice, mites and ticks. Mosquitoes may also be a nuisance in some areas. Most external parasites reduce growth, efficiency and reproduction, as well as adding another stress, perhaps increasing the susceptibility of the bird to disease.

Several insecticides are effective in controlling external parasites; however, some are no longer permitted for use on birds. Care should be taken in the selection and use of the proper materials. Check with your county agent or state diagnostic lab for a list of approved, effective products.

Toxins

Botulism - This is a type of food poisoning caused by eating materials containing the toxin produced by a bacterium, Clostridium botulinum. The clinical findings of poisoned birds are weakness, followed by paralysis of the neck, legs and wings, and finally, prostration and death. The feathers can be easily plucked. No lesions are apparent in the affected quail. Botulism can be prevented by keeping possible sources of contamination (such as spoiled foods, wet feed and dead animals) away from the birds.

Moulds - The major toxins of concern are those generally found in the feed or litter that are produced by moulds. The most common toxins affecting poultry seem to be aflatoxin and an oestrogen-like compound produced by Fusarium moulds. The symptoms of aflatoxicosis include an unsteady gait, leg weakness or paralysis, liver damage, small haemorrhages and, in many cases, a condition similar to rickets. The presence of aflatoxin in the feed and litter can be determined by laboratory tests. Although some degree of prevention may be obtained from antibiotic-vitamin mixtures, using fresh, clean, dry feed manufactured from uncontaminated ingredients will usually prevent mould toxin poisoning.

Other Toxic Substances - Quail are susceptible to certain types of seeds, such as those of the crotolaria plant, which may contaminate grain used in producing feeds. Other toxic materials such as insecticides, herbicides, certain minerals and pollutants may also cause an occasional problem.

Disease Treatment

Drug use

Early disease diagnosis and treatment is essential to good management. Contact your state diagnostic laboratory for information about what drugs are approved for use with bobwhite quail. There are situations where periodic use of a specific medication for a specific problem is necessary, but this should occur only under the direction of a competent diagnostician.

Treatment administration

Once the problem and the proper treatment have been identified, a decision must be made on how to administer the treatment. Many medications are available as water-soluble powders or liquids and/or as feed additives.

Some comments on these methods of treatment follow:

Water - Medicating birds through their drinking water is the most practical method of giving drugs, and a response is usually seen in three to four days. It is very important to follow the directions. Never give a heavier dosage than called for; it may do more harm than good. When giving water treatments, always consider the environmental conditions. If the temperature around the birds is warm, they will drink more water and, as a result, receive more medication.

Cool temperatures will have the opposite effect on consumption. Many drugs will be inactivated by hard water. Before mixing in antibiotics, it is usually best to acidify water by adding 2.5 ounces of apple cider vinegar per five gallons of water. "City" water also has added chemicals that sometimes interact with drugs. Follow the manufacturer's recommendations and/or consult an avian veterinarian.

Feed - This type of treatment usually takes at least five to eight days to cause a response. When a long-term medication treatment is prescribed, this is the usual way to administer it.

If a medication programme in both feed and water is used, be sure the two treatments are compatible and are not additive or antagonistic.

Handling Quail

Each time quail are handled, they are stressed and subject to injury. This can cause a loss of production, non-salable birds and cannibalism. Try not to move the birds under unfavourable weather conditions. When birds must be moved, use transfer boxes that are only six to seven inches deep. This will limit injuries from jumping and piling. Quail can be driven into transfer boxes or caught with a minnow net. Do not expose boxed birds to extended periods of direct sun in warm weather or to direct draughts in cold weather. Provide an adequate air supply into the transport boxes through ventilation holes.

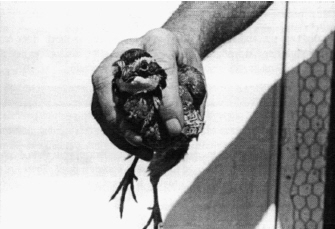

When handling the individual bird, grasp it with its neck between your first and second fingers and with your thumb and remaining fingers enclosing the body as much as possible (Figure 1). This method prevents the wings from fluttering and allows the legs to hang free. Never handle quail unless absolutely necessary, and never hold a quail by a leg, wing or head.

Enclosing the body with your fingers will prevent the wings from fluttering.

Releasing Quail

Quail should be released with the intent of recovering them by hunting shortly after release. It is difficult to establish a quail population in the wild by releasing pen-raised quail.

Locating a suitable area for release is important. The main considerations are availability of cover, food and water. Good results are generally obtained by releasing flight-conditioned birds as soon as they attain adult size and weight, but not earlier than 1 October. The highest recovery rate is experienced when releases are made periodically during the hunting season.

Plan to release the birds late in the afternoon so that they will feed and go to roost. A cardboard box six to seven inches deep and 24 inches square will handle approximately 20 birds. Whatever container is used, it should be shallow, have the top padded and have plenty of small air holes that keep out most of the light. Place the transporting container in the cover area where the birds are to be released. Open only one end, so the birds can walk out. Do not frighten the birds or cause them to scatter. Go back after the birds are out of the box and remove it. In situations where supplemental feed will be provided after release, feeding the same feed in the same feeders used before release is recommended. It may also be necessary to provide supplemental water in some conditions. The birds are usually released in coveys of 15 to 20 birds.

Processing

When quail are grown to be processed for meat, they should be slaughtered before six months of age. Younger birds will be more tender and the feathers will be easier to pick.

Birds to be processed can be killed by an outside neck cut and allowed to bleed for one minute. They should then be scalded for 30 seconds at a water temperature of 135°F. Feathers can be picked with small, commercially available, rotary drum pickers. Birds are picked in batches of 15 to 20 birds each, for 15 seconds per batch. After picking, the shanks, heads and necks are removed and the carcasses are eviscerated, including crop and oesophagus, by splitting the back.

Following processing, the carcasses should be chilled overnight in ice water to allow rigor to be completed. This will cause the meat to be more tender. If older birds are processed, it is usually beneficial to chill them overnight in five per cent salt water (iced) to partially tenderize the meat. The birds can then be prepared fresh or can be frozen for several weeks before cooking.

Eggs

Quail eggs may be prepared in essentially any form that chicken eggs are used. The flavour is very similar to that of the chicken egg but perhaps slightly more delicate. There is also about six to 10 per cent more yolk in the quail egg in relation to the remainder of the egg. It has a thin shell but a very thick, strong membrane that must be cut when opening a fresh egg.

Since quail eggs are small, they are used most often in hors d'oeuvres and as snacks. A common form of preparation is pickling. Tested pickling recipes are shown in the table. Mix the ingredients in hot water, bring to a boil, then simmer until used.

| Recipes for pickled quail eggs (1 quart)a |

Kansas Spicy Eggs

|

Dilled Eggs

|

Sweet and Sour Eggs

|

Red Beet Eggs

|

| a Maurer, A.J.,1972. Pickled eggs - A novel snack. Cooperative Ext. Prog., Univ. Wisconsin, Ext. Fact Sheet A 2455. |

Before cooking, freshly laid eggs that are to be used for pickling should be held for 24 to 48 hours at room temperature, or for five to seven days in an egg cooler. This will enhance peeling quality. To hard cook the eggs, place them in a pan, cover with cold water, bring the water to boiling, remove from heat, cover and allow to stand at room temperature for 20 minutes. Remove cover and cool the eggs with cold running water. Allow eggs to remain in cold water until removed for peeling. Place peeled eggs in quart jars and pour hot pickling solution over the eggs. Seal jars and cool at room temperature. Store in a refrigerator.

Acknowledgement: Appreciation is extended to Walter Walker, the author of the original Clemson University Extension bulletin 'Raising Bobwhite Quail for Commercial Use'.

January 2015