Business case for higher animal welfare

An interview with John Brunnquell CEO and founder of Egg InnovationFrom cage to cage-free, from animal ethology to regenerative agriculture, John Brunnquell has never ceased to innovate with his business, Egg Innovations. John shared with us the incredible journey he has taken to transform his business to provide higher welfare products for concerned consumers, based on a scientific understanding of hen behavior and the motivation.

Q: Hello John, can you please introduce yourself?

A: I'm John Brunnquell, the CEO and founder of Egg Innovations, where we produce free range and pasture eggs exclusively. I grew up on a family farm in Wisconsin, where we had 7000 chickens in cages. After high school, I pursued a bachelor's degree in agronomy and poultry science. In the late 80s, cholesterol was a priority in the United States, so I decided to complete a Master’s degree in poultry science with a specific focus on nutrient manipulation of shell eggs.

I walked into my first cage-free farm in the early 90s. This experience shattered everything I thought I knew about raising chickens: I simply couldn't wrap my head around the fact that chickens walking around could have a worse quality of life than a bird in a cage. I wanted to get a clearer understanding of what cage-free, free range and animal welfare meant. I felt there had to be some science to it. So, at the young age of 54, I returned to college and received a PhD in avian ethology, the study of hen behavior.

Along the way, my wife, Kathy, and I founded Egg Innovations in 1999. This company is committed to enabling chickens to live and behave naturally, but on a commercial scale.

Q: What are the core values of Egg Innovations?

A: We have three core pillars at Egg Innovations: we focus on the chickens, our people, and the planet. We take a holistic view to consider everyone we touch in our business. As for the planet, we aspire to leave the planet in a better place than when we found it. Those three value statements affect every decision that we make at Egg Innovations.

Q: You mentioned your PhD in avian ethology, can you please describe what this is and how it relates to laying hen housing?

A: We have a fundamental belief that every animal on this planet is hardwired to certain behaviors. Be it a llama, an elephant, a dog, a human, or a chicken, we believe that when you manage that animal consistent with their hardwired behaviors, good things should happen. Therefore, we put great emphasis on the native behaviors of chickens at Egg Innovations.

A chicken is hardwired to perch, dust bathe, to scratch, to pasture, and to socialize. When we looked at housing systems prevalent in the United States, we found that cages do not allow laying hens to perform the five natural behaviors:

- Perching: Given their ancestry roots of jungle fowl, which roosted in trees, chickens prefer to stand and clutch onto something. On our farms, we find 100% of the birds up on perches at night when that opportunity is provided. That is why we have 2 miles of perches in every building.

- Dust bathing: Chickens naturally want to dust bathe. This behaviour helps them cool down, get rid of parasites, and to spread their natural oils throughout their feathers.

- Scratching and pasture: Chickens are very exploratory and curious. They are highly motivated to explore their environment using their beaks and feet. Again, we found a conflict between this natural behavior and cages.

- Social: By nature, hens are very social animals. They regularly communicate with each other through different geiko calls, including information about the environment or the presence of predators overhead. Anyone that has worked with laying hens before will notice that when you walk into a barn or on a pasture, you can hear the calls that indicate good welfare. Although hens require space to move around, they also want to stay in visual contact with each other. Therefore, when we set up our pastures, we try and strike the balance between giving them enough space to move around, so they're not overgrazing and destroying the pasture, but also ensure they can see each other.

Q: Enrichment is commonly discussed as an important component of layer housing. Can you please share how Egg Innovations implements this?

A: To a chicken, being placed a soccer field or hay field is a highly unpleasant experience. There's fear of predators overhead when they have no place to hide, and they also have nothing to explore. Enrichment is critical for birds to fulfil their curiosity. When our farmers have old equipment, they put that in the pasture to give the chickens opportunities to explore. The chickens will go underneath them, on top, perch, and again, enjoy expressing all their natural behaviors. They prefer vegetation to bare ground, and they want an enriched vegetation with a variety of trees, shrubs, and grasses. Many of our farms are built in the woods where the hens can duck underneath and climb over logs. At Egg Innovations we try to first understand the behavior of hens, then we create a living environment tailored to their needs. Chickens are sentient beings and will have positive experiences when placed in a suitable environment. This then translates to higher productivity.

Q: What is your business model for high animal welfare products?

A: We have learned from the egg industry in the United States. Vertical integration is a critical part of the industry, which means having control of pullet facilities, feed mills, layer facilities, and grading facilities. When you separate and outsource parts of the supply chain, everyone providing that service is entitled to a profit. When you own these facilities, you have more flexibility and control over the operating expenses. This means that we can operate most facilities at a breakeven and put all the margin on layer facilities. We find this to be a significantly less costly production model.

We started Egg Innovations with multiple pullet facilities. We don’t buy pullets as we own them from day one, and we contract farmers to provide us labour and access to their buildings. For growers, we contract farmers to provide us with the facility, utilities, and labour, while we have full control of the birds, feed, and transportation. By the end, we're not buying any eggs, we already own them. We're just paying contractors management fee on a per dozen basis.

For the feed, we purchase grain locally when we can. However, in some cases like organic, we depend on the international market. Our layer facilities are located in the Midwest, United States. We bring all of the eggs into a single grading facility, then we distribute them across the nation.

Q: It seems like your business depends quite heavily on contractors. Can you please provide more details on how you make these contracts?

A: Growing up on a farm, it is very important for me that we provide good contracts to our farmers. This means that the contracts are long, up to 12 years, and that we share the risks and rewards of the business. For example, I’ll give a farmer 20,000 hens, each hen costs around $10, so I’m giving the farmer $200,000 of my livestock. The only way I get that money back is through the dozens of eggs they produce. The more eggs I get, the lower my cost per dozen because the cost of pullets is fixed. I truly win when the farmer wins.

We provide farmers with technical support, nutrition and veterinary services, in order to facilitate them to achieve optimum hen productivity. We also deliver feed tailored to the bird’s productive level.

Q: Besides from the pullet and layer facilities, how do you manage the feed mill and grading facility?

A: In 2014, we built a state-of-the-art feed mill. We mill our own non-GMO feed and organic feed. This gives us flexibility to work with local grain farmers where we can adjust the diets as needed. Again, we operate the feed mill at a breakeven point without putting extra profit on the finished ton of feed.

A year later, we built a new grading facility, again state-of-the-art and runs on mobile equipment. Currently we grade about 8.5 million eggs per week, and we're preparing to expand on that. All of our production throughout the Midwest comes into this grading facility. One of the things we learned is that it’s simply much less expensive to produce the eggs where the grain is, thus shipping the eggs to the grading facility and then to the markets, rather than to produce the eggs where they will be consumed locally,. Therefore, all of our contract growers are located in five states, from Wisconsin in the North to Kentucky in the South. We have approximately 50 farms raising 1 million hens in total.

Q: What is different about your laying hens compared to hens from other farms?

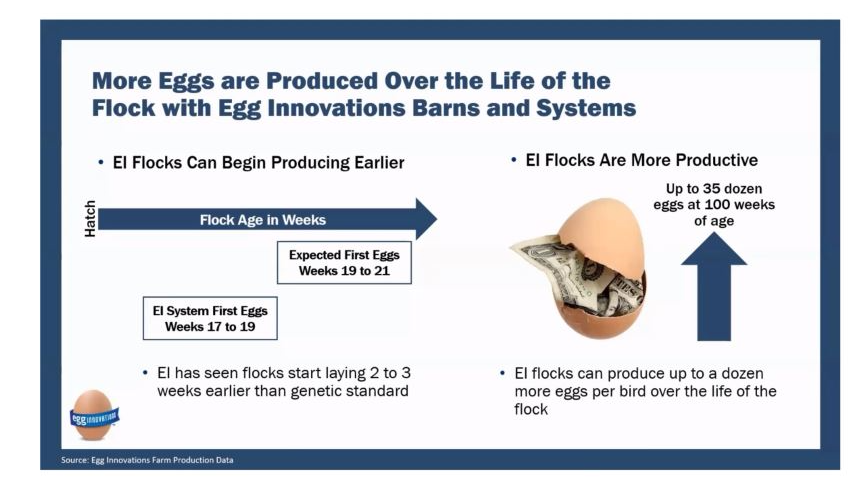

A: We produce more eggs from our hens over the lifetime of the flock. With vertical integration, we control when they come into production and when their laying period ends. Our hens simply live longer and are more durable. We lay them out to approximately 95 to 100 weeks of age.

My mom used to always joke that if you eat five pounds of dirt before you're married, you're going to be healthy. And in many ways, it’s the same for our birds. When we give hens opportunities to exercise, they develop a more robust immune system and can cope with environmental stressors, whether it’s the temperature dropping from 70 degrees one day to 50 degrees the next, or the weather changing from rain to sun.

Q: How do you communicate what you’re doing to your consumers?

A: We know that our consumers probably are never going to visit our farms. Not because we don't want them to, but simply because geographically they may be located far from us. We stand by the phrase; ‘if you have guilt by association, you have credibility by affiliation’. To build our credibility, we carry a number of third-party certifications, including Certified Humane for animal welfare, Non-GMO Project for the quality of the grain used in our feed, United Egg Producers for the egg industry standard, and Orthodox Union for our kosher eggs. Recently, we've added the regenerative agriculture certification.

We've taken the most rigorous standard within each one of these certifications, whether it's how many inches per perch per bird, or how many water nipples per bird, we've taken the highest expectation of each of the standards and made that our baseline. We put in a lot of effort and went through multiple audits, but it gives us tremendous opportunity to grow our business.

Q: You named the company ‘Egg Innovations’, can you please describe some innovative decisions you’ve made that changed the company?

A: The cost of building a new poultry building has gone up significantly since I first started in the industry. For 20,000 hens, it was about $350,000, and now it's close to $1.2 million. If it costs the contract grower more to put up a building, I have to pay them more for a dozen eggs.

Three years ago, we took an innovative step by moving to aviary systems. It was a revolutionary approach to free range and pasture egg production. It had never been done before in the United States. By increasing the volume with height, we were able to put 30,000 birds in a building that was 50 feet wide and 500 feet long, instead of 20,000 birds. This lowers the cost of entry, capital costs per hen, and ultimately, the cost of a dozen eggs. Furthermore, the new aviary systems provided us some excellent technical improvements. We now have manure belts that removed manure daily. In the old model, we only pulled out manure once in between the flocks. Our ventilation and lighting controls have also been updated to be much better quality. We started using Combi vent, or combination vent; when the temperature is below a certain point, the building will ventilate with cross ventilation horizontally. When the building gets above a certain temperature, the computers will switch to tunnel ventilation. This technology optimises the air quality, which leads back to improving hen welfare and improving feed efficiency.

Another important change after using aviary systems is that it reduces the number of producers that we need. Obviously, one farmer with a 40,000-bird aviary replaces two farmers who have a 20,000-bird flat building each. We built our first aviary system in 2021 and we are very pleased to say that the birds use the range very effectively.

Q: Regenerative agriculture is an emerging concept in animal agriculture. How can this be incorporated into egg production?

A: One of our core pillars of the business is the planet, so we decided to engage with regenerative agriculture. For those that are not familiar with this concept, regenerative agriculture was introduced as a solution to mitigate issues with global warming, especially carbon emissions. After learning about these practices, we believe the future is in regenerative agriculture.

Although we are not a huge company, we’re not small either. With approximately 1500 acres of pasture under our management, we decided to incorporate regenerative agriculture into our practices by starting with some of the basic principles. First, we tried to understand the context of our farm operations. A farm in one state or geography is different from another farm in a different location. The vegetation can be different, or the layout of the land can be different, therefore, regenerative agriculture requires localized knowledge.

Secondly, we want to minimize bare soil. Monocultures such corn, maize andwheat release a large amount carbon into the air. When you have soil cover, you keep the carbon in the ground. It is also important for us to maintain a living root zone all year long.

Next, the vegetation chosen should be diverse. We assessed all of our pastures and decided to plant a variety of grasses, broad leaves, and shrubs, in addition to trees. These plants also attract pollinators like bees and enrich the pastures for the hens. By adding livestock to the pasture, we created an integrated process between the soil, plant, and animals.

Q: What are the products you sell to consumers?

A: We sell two types of eggs, free range eggs and pasture eggs. Animal welfare has become the fastest growing trend in the United States. Specifically, ‘pasture-raised’ and ‘free-range’ is growing at 30% and 20% annually, respectively. There are also clear signs that the cage market is shrinking.

First, ‘Blue Sky Family Farms’ is our entry level brand. This is a lower cost option solely focused on animal welfare. This gives egg consumers a better alternative to store-brand or caged eggs. The second one is ‘Helpful Eggs’, which we launched last year and is now the fastest growing brand in the United States. We took our animal welfare standards and added in the regenerative practices. By having two products at different prices with different focuses, we allow consumers to choose based on what they can afford and where their passions lie.