Cobb Breeder Management Guide: Parasite control

Learn how a good sanitation program can prevent and control ectoparasitesPart of Series:

< Previous Article in Series Next Article in Series >

Editor's note: This article is an excerpt from the Cobb Breeder Management Guide and additional articles will follow. The Guide was designed to highlight critical factors that are most likely to influence flock performance. The management recommendations discussed were developed specifically for Cobb products. The recommendations are intended as a reference and supplement to your own flock management skills so that you can apply your knowledge and judgement to obtain consistently good results with the Cobb family of products. To read or download the complete Guide or to view Cobb's other management guides, click here.

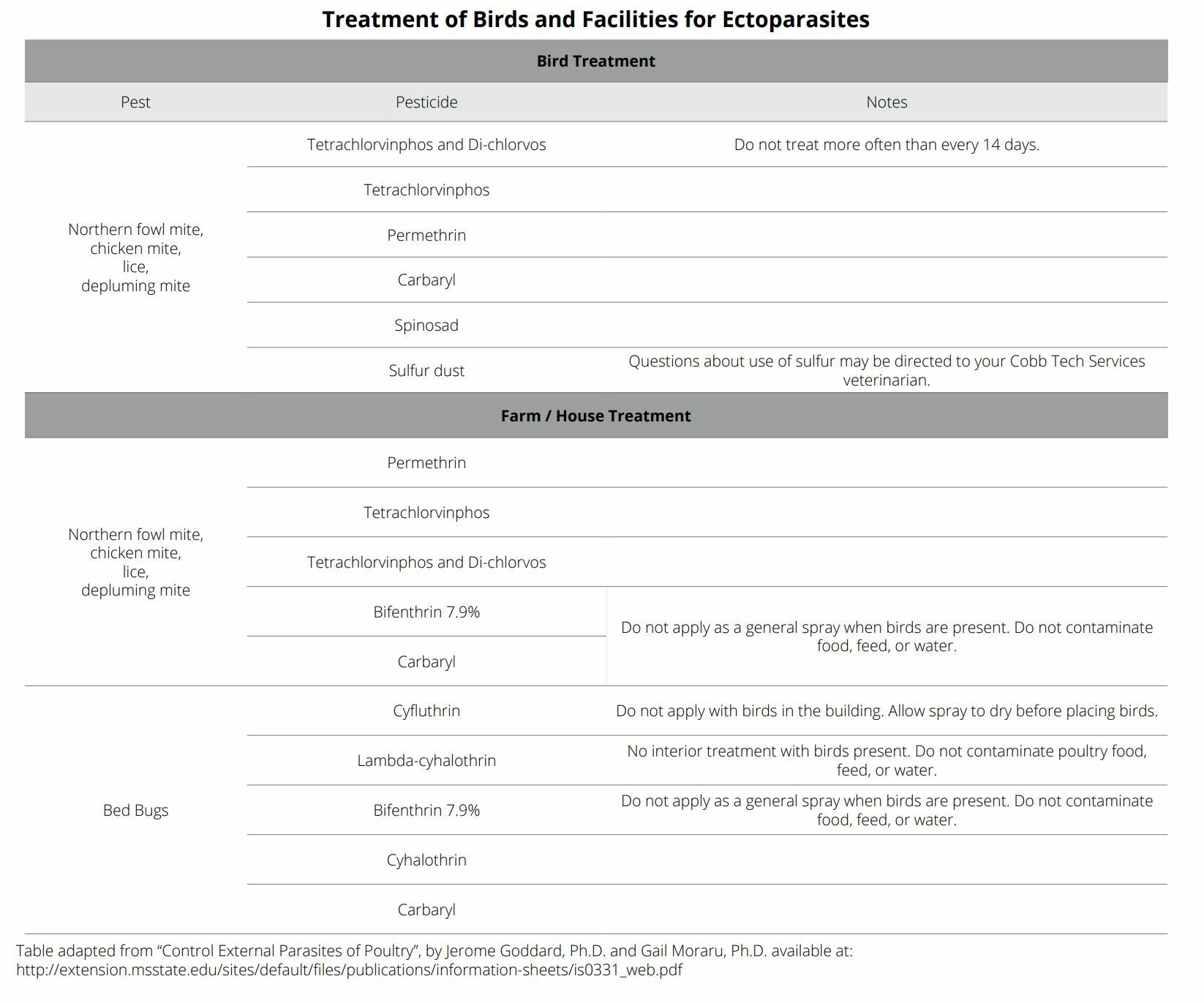

Ectoparasites feed on the outside of the body and can cause considerable issues in poultry breeder operations. Ectoparasites can increase floor egg numbers as hens are reluctant to enter nests that contain parasites. Furthermore, ectoparasites can cause skin lesions which can lead to skin infections and may carry and spread diseases. A good sanitation program and use of targeted pesticides can prevent and control ectoparasites.

Mites

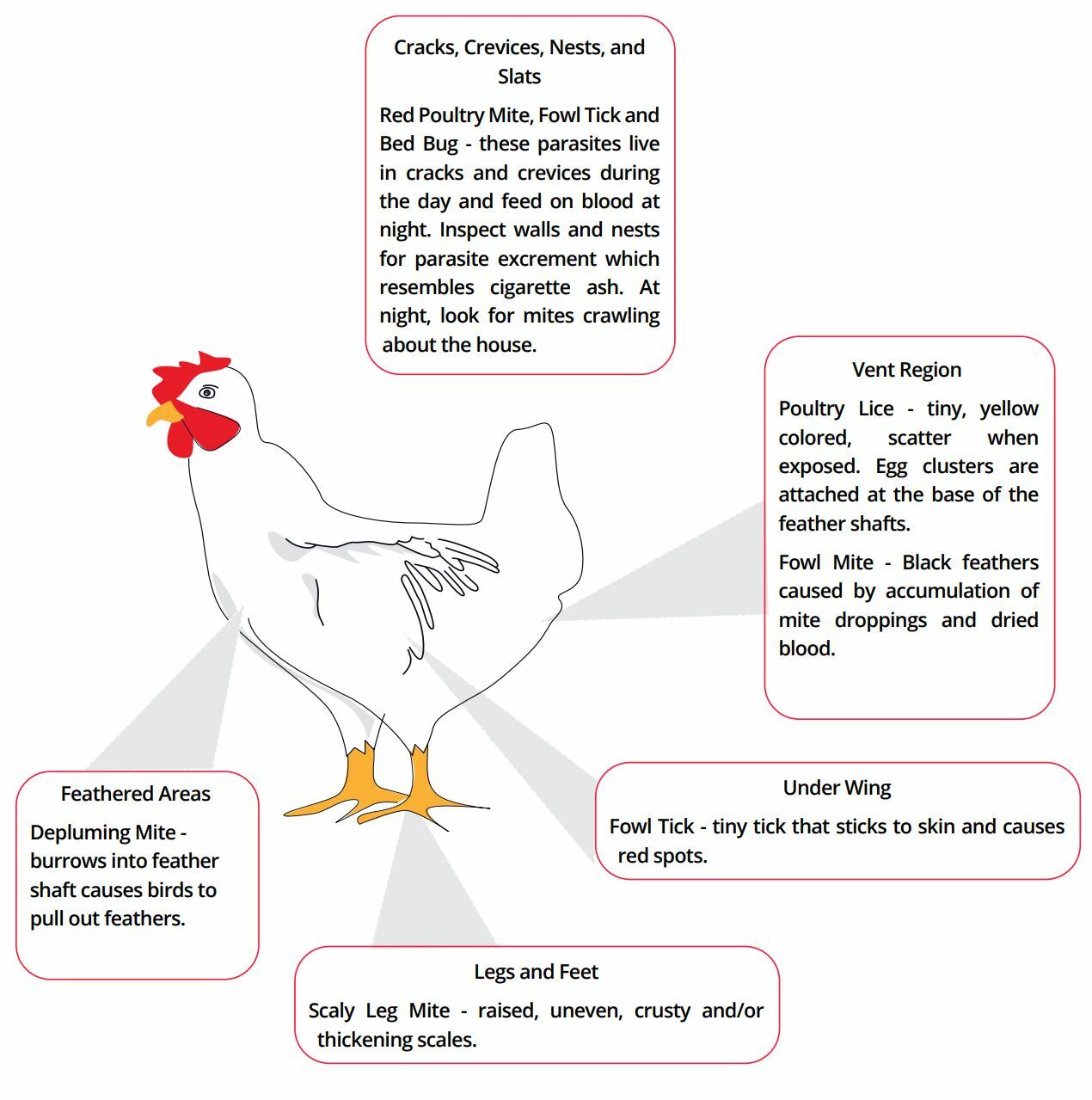

There are several species of mites that infect poultry. The Northern Fowl mite is usually located around the vent. Therefore, they are often found on eggs and may be detected by staff handling eggs. Scaly leg and depluming mites infest the legs and feet and base of the feathers, respectively.

If environmental conditions are good (temperature and humidity) some mites can live apart from birds for several weeks. Therefore, even with downtime, mites can survive to infect a new flock. Infestations tend to be worse in cool weather and on young birds.

Wild birds are known carriers of mites. Prevent nesting of wild birds on or around poultry houses. Mites can be carried into the house by equipment and egg flats. They live in cracks, crevices, nest boxes and walls (nest boxes and slats offer ideal habitats) during the day and feed at night. Depending on the infesting species, infestations can cause pale combs and wattles, crusty skin on the legs, and birds pulling out their feathers.

Lice

Lice chew on the skin and do not suck blood. Lice live entirely on birds and only leave the bird to attack a different bird. Control and prevention strategies are the same as those for mites. Lice will not preferentially infest one part of the body, so the entire bird should be inspected. White egg masses at the base of the feathers are the easiest way to identify a lice infestation.

Bed bugs

Bed bug behavior is similar to mites. They live in cracks and crevices during the day and feed at night. Bed bugs can survive for months apart from the birds so downtime will not alleviate a bed bug issue. Inspect cracks, crevices, and eggs for bedbugs which will appear as black spots.

Fleas and ticks

These parasites are occasionally found in breeder operations. Most pesticides that are used to treat other ectoparasites are also effective against fleas and ticks.

Internal parasites

The main groups of internal parasites infecting pullets and breeders are worms (nematodes; cestodes) and protozoa (coccidia species). The most common worms afflicting poultry are members of 2 taxonomic classes, nematodes and cestodes. Nematodes are the most important roundworms and include Ascaridia galli (large roundworm), Heterakis gallinarum (ceacal roundworm) and Capillaria spp. (hair worms). Cestodes are the most important tapeworms and include Raillietina spp. (large tapeworms) and Davainea spp. (small tapeworms).

- Worm eggs may be ingested directly, or infected earthworms may transport eggs or host partially developed larvae.

- The cecal worm eggs may remain viable for months in the environment and can carry the parasite causing blackhead (Histomonas meleagridis) which causes flock mortality rates of up to 15 %.

- Cestodes (tapeworms) can infect older birds. Beetles and snails can act as an intermediate host making pest control important parts of controlling parasites.

- Tapeworms are difficult to treat and control may be more easily achieved in intensive systems by controlling the intermediate hosts.

Strategic deworming program

- The preventative deworming program should be performed during rearing.

- The strategy should be based on the degree of field challenge.

- Flocks placed on concrete floors will be less challenged compared to flocks placed on dirt floors.

- Seek local veterinary advise for the best strategy under your conditions.

Deworming via feed

- A 7-day treatment with Fenbendazole (60 ppm), Flubendazole (30 ppm), and Mebendazole (60 ppm) two times during growout (10 and 19 weeks of age) is effective.

Deworming via drinking water

- Each deworming treatment should consist of two different applications of the product with an interval of 10 to 14 days between the two. Each application should last between 3 to 4 hours.

- Under low challenge conditions, the first treatment at 8 and 10 weeks of age and second treatment at 19 to 21 weeks of age is recommended.

- Under high challenge conditions, the strategy could consist of up to 4 different treatments. Example: 3 and 5 weeks of age, then 8 and 10 weeks of age, a third treatment at 14 to 16 weeks of age and the last one at 19 and 21 weeks of age.

- The selection of the deworming product is key to a successful program. Use a broad-spectrum product that will treat as many worms possible and at different stages.

- There are many types of dewormers available but only few can treat different species of worms and at different stages. The active ingredient Levamisole hydrochloride at 40 mg/kg dosage is effective against most worms infecting poultry and at different stages. However, it can only be administered during growing.

- Piperazine is only effective against roundworms.

Coccidiosis prevention

The goal of the coccidiosis program is to help the flock develop immunity. Cocci drugs such as amprolium should only be given as needed as they have the potential to inactivate accrued immunity and result in subsequent coccidiosis or necrotic enteritis outbreaks.

The prevention program consists of two very important steps:

- Vaccination. Birds can be vaccinated during the first 5 days of their lives. However, spray vaccination at the hatchery provides a more controlled and effective process.

- Litter management at the farm. When birds are given more space within the house, transfer litter from the brooding area and mix it with the litter in the new space. This step is critical during the first 3 to 4 weeks so chicks keep ingesting the vaccine (oocysts) from the litter to complete the vaccine oocyst cycling needed for immunity.

Important points for coccidiosis vaccination by spray cabinet:

- Coccidiosis vaccines must be stirred or agitated gently and continuously to ensure that the oocysts stay in suspension. If oocysts are allowed to settle to the bottom of the bottle, significant variation will occur in the actual oocyst dose delivered.

- Coccidiosis vaccines are generally delivered with a fan pattern while respiratory vaccines are usually sprayed with a cone-shaped pattern.

- Coccidiosis vaccines utilize a larger droplet size and the volume of vaccine delivered is approximately 21 ml (0.71 oz) per box.

- The reconstituted vaccine is dyed in order to stimulate preening postvaccination and vaccine consumption.

- After vaccination, the chick boxes should be placed in an area with sufficient light to continue stimulating vaccine consumption by preening.