Coccidiosis in Poultry

The history of coccidiosis and its control by vaccination, established in-feed anticoccidials and newer botanical products from Meriden Animal Health.Introduction

|

|

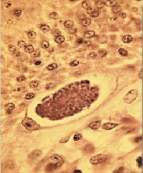

Coccidiosis is a realistic problem and one of the most important diseases of poultry worldwide. It is caused by a protozoan parasite known as Eimeria that invade the cells of the poultry intestine. Species of coccidia which commonly affect poultry are Eimeria tenella, E. acervulina, E. necatrix, E. maxima and E. brunetti. The disease is characterised by enteritis, diarrhoea and mortality. The bird develops reduced ability to absorb nutrients, which results in weight loss and eventually death. Subclinically, it is manifested by poor performance, impaired feed conversion, poor flock uniformity and poor growth. Coccidia can also damage the immune system and leave poultry more vulnerable to pathogens like Clostridium, Salmonella and E. coli.

The disease is considered as one of the most severe health and economical problems in poultry that causes an enormous loss to poultry producers worldwide.

The History of Coccidiosis

Even though coccidiosis is known to affect almost every species of animal on earth, our first attempts at treating coccidiosis dates back to an outbreak in poultry some 60 years ago. Poultry was already an important source of meat at the time. The drug of choice for the treatment of coccidiosis then, based on availability, was the sulphonamides.

Through further experimentation, poultry producers in the United States found in the late 1940s that the most economical method of preventing the disease and controlling the problem was via continuous usage of sulphaquinoxalines in the feed of the chickens. This not only reduced the mortality caused by the protozoan parasite but also lessened the morbidity of the disease in poultry.

Since the 1950s, various types of anticoccidials have been produced from different drugs and chemicals. Some of the older chemicals such as amprolium and nicarbazin are still being used today. Most are no longer in use or allowed in various countries due to proven toxicological findings or a lack of efficacy due to the development of resistance by the coccidia it was designed to treat.

In the 1970s, a new class of antibiotics was discovered. These were named the ionophores, and eventually replaced the earlier chemical compounds. Ionophores are unique because they permit a small amount of coccidia to survive and complete their life cycle within the intestines of the bird, enabling the birds to develop a certain level of immunity. This allows a greater degree of protection against the parasite and is a very efficient method of control. However, these more recent developments were still unable to address the issue of resistance and soon enough, most species of coccidia had developed resistance to all the ionophores available in the industry.

The Battle Against Coccidiosis

An outbreak of coccidiosis in a poultry flock has a very high negative and economical impact on the flock as well as for the poultry producer. There is an immediate and considerable drop in production figures and the recovery and reestablishment period after treatment is slow. Some flocks never fully recover or regain their full production potential. Hence, it is a well-recognised fact that treatment alone cannot prevent the economical losses. It is well established within the poultry sector that the only choice is therefore prevention of the disease. However, an effective and sustainable prevention and control programme against the disease is not easy.

Coccidiosis is particularly difficult to combat because several different species of Eimeria exist in the field. Poultry may become infected with different species because the immunity that develops after infection is specific only to one species. Eimeria has a very complex life cycle that involves many developmental stages within the host cells. Each Eimeria type is able to infect only one host species and each attacks a different segment of the intestine in their host.

The disease carries losses for the producer in the form of mortalities, reduced market value of the affected birds and sometimes culling or delayed slaughter time. Another predisposing factor is the confined host rearing conditions, which lead to an increase in the numbers of oocysts, which are ingested by poultry via the litter. These lead to destruction of the integrity of the intestinal mucosa and interfere with nutrient absorption, ultimately causing diarrhoea, which in turn causes high medication costs. Ultimately, all these setbacks lead to huge losses for the producer.

Another factor is the increasing incidence of drug resistance to field strains of coccidia. The conventional methods to control the disease are by using certain coccidiostats or coccidiocidal drugs. Producers are adding a number of anticoccidial drugs to commercial feed to control the recurring coccidial challenge. In the case of salinomycin, it is known that at approximately day 28 of the broiler production period, performance declines in birds receiving the anticoccidial due to the presence of subclinical coccidiosis. Under normal management conditions, this is a typical occurrence when this ionophore is used.

To prevent widespread resistance to the narrow range of anticoccidial drugs available in the field, nutritionists and veterinarians have resorted to devising and implementing many different forms of complex anticoccidial shuttle and rotational programmes in an attempt to achieve optimal efficacy with minimal side effects. However, the design, implementation and monitoring of such programmes has become extremely complicated and fraught with obstacles and risks. For example, poultry flocks cannot be treated with nicarbazin during early autumn or spring because sudden heat waves can result in high mortality, even in young birds. Albeit still valuable to the industry, ionophores also have their own dangers. Detectable residual levels of coccidiostats have occasionally been found in commercial broiler meat and table eggs.

A relatively common problem that poses devastating consequences is the accidental feeding of diets containing coccidiostats to non-target animals. For instance, turkeys fed rations containing salinomycin may encounter an increase in mortality, whereas broiler breeders fed rations containing nicarbazin may be affected by a drop in egg production and infertility.

Last but not least, producers need to consider the extra time and money spent by the feed mill for flushing systems of coccidiostat residues, the planning and mixing of various different batches of medicated feed, and attempts to avoid cross contamination of drug-free withdrawal feed. Residual effects, if found in the poultry meat or eggs, may pose a serious problem for producers who wish to export their produce to countries where legislation requires drug and residue-free chicken meat and eggs and where demands for such healthy produce are on the rise.

Coccidial Vaccinations: A Boon or a Bane?

|

|

Obviously an alternative system to control coccidiosis is by vaccination. Currently, a number of coccidial vaccines have been developed and used commercially. Most coccidial vaccines include a low dose of the live parasite as a key ingredient to stimulate protective immunity. These have been used in millions of chickens. However, the parasite can still cause disease in vaccinated chickens if their immune systems are already compromised, damaged or suppressed by other infectious agents.

In the field, once birds have been exposed to coccidia, they develop immunity after approximately three cycles of oocyst production. Although live or attenuated parasites have been widely used as a commercial vaccine, antigenic variability between the Eimeria species present in the vaccine and those in the field restricts the effectiveness of commercial vaccines.

There is also a price to be paid for protection against a potential threat. This could be in the form of the high cost of vaccines, time spent to administering the vaccines and losses due to vaccine reactions in live vaccines and localized tissue damage in killed vaccines.

The disadvantages associated with the live vaccines are problems with uniform vaccine application, excessive vaccine reactions, unwanted spread of the vaccinal viruses, extreme handling requirements needed to maintain viability of the vaccinal organisms and last but not least, the emergence of necrotic enteritis, an enterotoxaemic disease that usually accompanies coccidiosis, caused by Clostridium perfringens. The disadvantages of the killed vaccines are increased costs in terms of labour and the product itself, slower onset of immunity, a narrow spectrum of protection and localized tissue damage at the site of injection.

Furthermore, one cannot totally eliminate the risk of vaccination failure. A vaccination failure occurs when, following vaccine administration, the chickens do not develop adequate protection and are susceptible to a field disease outbreak. There are several factors, including high levels of maternal antibodies, various stressors such as environmental extremes, inadequate nutrition, parasitism and other concurrent diseases that can also contribute towards vaccine failure. Improper handling or administration of the vaccine should also be considered.

A New Natural Weapon: Botanical Warfare!

There is now a solution, a benchmark product that is competitively priced which functions not only as a replacement for coccidiostats and antibiotic growth promoters but which can also provide many other benefits that lead to supreme productivity and animal health, which in turn spells better profit and a higher return of investment for the poultry producer.

Orego-Stim is a natural feed additive used in poultry production worldwide. It has been extensively researched and tested, and is able to increase the performance of poultry production by improving the feed conversion ratio (FCR) as well as increasing the body weight gain of broilers. It also helps to reduce mortality caused by gastrointestinal diseases by preventing the occurrences of gastrointestinal pathogen invasion. Its active components effectively kill these microorganisms, which include both gram positive and Gram-negative bacteria upon contact within the gut of the animals.

|

|

| Diagram (a) shows unspecified bacteria before treatment with Orego-Stim® | Diagram (b) shows the same bacteria after treatment Orego-Stim®. Complete cell lysis is clearly visible |

Orego-Stim is also able to control coccidiosis in all phases of poultry production. In contrast to antibiotic growth promoters and coccidiostats, there has been no evidence of bacterial or coccidial resistance from using Orego-Stim, simply because its main constituents are phenolic, making its mode of action is a straightforward and primitive one. There is no withdrawal period and Orego-Stim can be safely used right until the slaughter period.

In humans and animals, the upper layer of enterocytes is constantly shed and replenished every four to seven days. Orego-Stim speeds up this natural renewal process, creating an environment that is hostile to the coccidial life cycle. The sporozoite-infected cells are thus shed before development of the merozoite stage, which causes the main clinical signs of coccidiosis outbreaks. This disrupts the life cycle of the coccidia, resulting in effective control and prevention of coccidiosis.

|

|

|

| Figure 1. The effect of Orego-Stim on sporozoite-infected enterocytes within the lumen | ||

The rapid shedding of the intestinal cells also prevents thickening of the intestines caused by E. coli and other pathogenic bacteria that may be potential secondary invaders. Hence, the accelerated rate of epithelial cell turnover results in lesser contamination of the emerging enterocytes and improved absorption capacity for nutrients.

On the other hand, Orego-Stim encourages the build-up of immunity against coccidiosis, by allowing small amounts of oocysts to undergo and complete their lifecycle in the intestinal cells. This is often just enough to stimulate an immune response via activation of the Bursa-derived cell-mediated immunity, which releases macrophages, lymphocytes and natural killer cells to provide a longer-lasting immunity against coccidiosis with each cycle of oocyst production.

At the same time, Orego-Stim can prevent incidences of necrotic enteritis that usually accompany outbreaks of coccidiosis in poultry. Intestinal colonisation by Clostridium perfringens not only decreases growth and feed utilisation, but can also result in high mortality. Orego-Stim is easily able to kill Clostridium perfringens in the gut, thus preventing further complications of mixed infections.

In a trial conducted in the USA by Colorado Quality Research Incorporated, Orego-Stim was fed to chicks that had been challenged with coccidiosis oocysts in order to evaluate the ability of this product to protect against a coccidiosis challenge in comparison to a commonly used ionophore coccidiostat, which was salinomycin. The results indicate that the Orego-Stim gave effective protection against the coccidiosis challenge. The level of protection achieved by the Orego-Stim group was similar to the protection provided by salinomycin at 55 grams per tonne.

|

|

| Figure 2. Orego-Stim: weight gain (shown as a bar) and feed conversion (line), 11-19 Days | Figure 3. Orego-Stim: coccidiosis lesion score on day 19 |

In the same experiment, performance of chicks fed Orego-Stim in the presence of a necrotic enteritis challenge was also evaluated. Orego-Stim was compared with bacitracin methylene disalicylate (BMD) in this part of the experiment. Results showed that Orego-Stim gave effective protection against the necrotic enteritis challenge model. The level of protection achieved by Orego-Stim was similar to protection provided by BMD at 27.5 grams per tonne.

|

|

| Figure 4. Orego-Stim: weight (shown as a bar) and feed conversion (line), 0-11 Days | Figure 5. Orego-Stim&: weight (shown as a bar) and feed conversion (line), 11-29 Days |

|

|

| Figure 6. Orego-Stim: necrotic enteritis score at 29 days |

Orego-Stim Application Rate for Control of Coccidiosis in Poultry

It is Meriden Animal Health's recommendation that Orego-Stim be applied continuously as a prophylaxis for control and prevention of coccidiosis, rather than at higher dosages for treatment. There are currently two application schemes, one using only the Orego-Stim Liquid (OSL) and the second using mainly Orego-Stim Powder (OSP) plus some OSL.

Scheme A (Orego-Stim Liquid only)

Week 1: Add OSL at 300ml per 1000 litres of water.

Week 2 onwards: Add OSL at 150ml per 1000 litres of water.

Critical periods*: Increase the OSL dosage to 300ml per 1000 litres of water.

Scheme B (Orego-Stim Powder plus Orego-Stim Liquid:

Week 1: Add OSP at 300g per tonne of feed together with OSL at 150ml per 1000 litres of water.

Week 2 onwards: Add OSP at 300g per tonne of feed.

Critical periods*: Add extra OSL at 150ml per 1000 litres of water.

Note:

*Critical periods are defined as period of stress and disease challenge, which could be caused by vaccinations, transportation, change in environment, overcrowding, changes in feed quality etc.

Critical periods usually lead to a decrease in feed consumption, which causes the birds to lose the protection offered by Orego-Stim Powder in the feed. At the same time, it has been known that stress-affected birds drink more water during critical periods, so by adding Orego-Stim Liquid to the drinking water, they will be able to get the protection they need when they drink.

The aim should be to supply extra Orego-Stim to the flock, starting 1-2 days before the onset of these critical periods and to continue up to 1-2 days after.

Further Reading

| - | Find out more information on the diseases mentioned in this article by clicking here. |

August 2009