Colibacillosis in Layers: an Overview

A review of the aetiology, routes of transmission, clinical signs, diagnosis and intervention strategies against colibacillosis in pullets and laying hens from Hy-Line International.Introduction

Colibacillosis, a syndrome caused by Escherichia coli, is one of the most common infectious bacterial diseases of the layer industry. E. coli are always found in the gastrointestinal tract of birds and disseminated widely in faeces; therefore, birds are continuously exposed through contaminated faeces, water, dust and the environment (Charlton, 2006). Colibacillosis causes elevated morbidity and mortality leading to economic losses on a farm especially around the peak of egg production and throughout the late lay period.

Colibacillosis often occurs concurrently with other diseases making it difficult to both diagnose and manage. In most field cases, colibacillosis tends to manifest after a bird has experienced an infectious, physical, toxic and/or nutritional challenge or trauma.

This condition is characterised by the presence of exudations in the peritoneal (abdominal) cavity including serum, fibrin, and inflammatory cells (pus). Fibrin, a white to yellow material, is the product of the inflammatory response in the chicken and can be seen covering the surfaces of multiple organs including the oviduct, ovary, intestine, air sacs, heart, lungs and liver.

Colibacillosis is a common cause of sporadic death in both layers and breeders but can cause sudden increased mortality levels in a flock. Inflammation of the oviduct (salpingitis) caused by E. coli infection results in decreased egg production and sporadic mortality, and it is one of the most common causes of mortality in commercial layer and breeder chickens (Nolan et al., 2013).

Colibacillosis in neonatal chicks can also be a consequence of poor chick quality and sanitation in the hatchery, leading to early chick mortality.

| Localised or systemic infections and syndromes caused by avian pathogenic E. coli (Nolan et al., 2013) |

|

| Localised infections | Coliform omphalitis / yolk sac infection Coliform cellulitis (inflammatory process) Swollen head syndrome Diarrhoeal disease Venereal colibacillosis (acute vaginitis Coliform salpingitis / perotonitis Coliform orchitis / epididymitis |

| Systemic infections | Colisepticaemia Haemorrhagic septicaemia Coligranuloma (Hjarre's disease) |

| Colisepticaemia sequelae | Meningitis Encephalitis Panphthalmitis Osteomyelitis Synovitis |

Aetiology

The aetiology of colibacillosis can be either due to primary infection with avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) or secondary (opportunistic) infection after a primary insult has occurred. E. coli are gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria considered normal inhabitants of the avian digestive tract. While most strains are considered to be non-pathogenic, certain strains have the ability to cause clinical disease. Pathogenic strains are commonly of the O1, O2 and O78 serotypes (Kahn, 2010).

There are many different serotypes of E. coli with 10 to 15 per cent of the serotypes considered pathogenic for birds. Other bacterial agents (e.g. Pasteurella multocida, Streptococcus sp., Klebsiella sp. etc.) and non-infectious factors usually predispose a bird to infection or contribute to disease severity. If the incidence is high, culture should be done to differentiate E. coli from other bacterial pathogens (Kahn, 2010).

Since E. coli is a common inhabitant of the intestine, it is widely disseminated in faecal material and litter. Additionally, contaminated feed, feed ingredients, drinking water, and rodent droppings can all be a source of E. coli infection for a flock. Due to continuous bacterial exposure in the environment, colibacillosis can affect birds at any time throughout the grow and lay periods. Although all ages of birds are susceptible to colibacillosis, younger birds (those grow period) are more commonly affected with greater disease severity than older birds.

Colibacillosis is a common cause of sporadic death in layers, but in some flocks it may become the major cause of death prior to or after reaching peak egg production (Kahn, 2010). In general, colibacillosis results from “respiratory origin” during the peak egg production period and from a “vent origin” in the late lay period.

| Factors pre-disposing to colibacillosis | |

| Predisposing factors during peaking period |

Multi-age complexes Exposure to endemic mycoplasmas (M. gallisepticum or M. synoviae) and/or infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) Poor ventilation with high levels of dust and/or ammonia Stress of production in a young developing bird High levels of circulating endogenous hormones (especially oestrogen) |

| Predisposing factors during late lay period |

Vent trauma, non-lethal vent cannibalism, and/or partial prolapse Too much light intensity Small-framed birds Excessively large egg size Excessive fat pad |

Routes of Transmission

E. coli can enter the body by various routes, all of which can lead to colibacillosis.

1. Respiratory tract

Inhalation of contaminated dust is the most likely source of E. coli infection (colibacillosis) for poultry. Additionally, damage to the respiratory tract from an infection (e.g. Newcastle disease virus, infectious bronchitis virus, M. gallisepticum, P. multocida, infectious laryngotracheitis, etc.) or irritation from dust or ammonia can lead to a secondary bacterial respiratory infection. Adverse reactions from routine vaccinations can also cause damage to the respiratory tract. Furthermore, any breakdown of the mucosal lining in the trachea has the potential to allow pathogenic bacteria to enter the blood stream which can lead to septicaemia.

Bacteria can persist for long periods of time under dry conditions; therefore, it is important to monitor and regulate the amount of dust in a poultry house. Ventilation systems may not be effective in removing dust from houses in most modern layer complexes, especially evident during winter with restricted ventilation leading to increased accumulation of dust and ammonia. Increased ammonia levels at 25 to 100 parts per million (ppm) can paralyse the cilia (small, hair-like structures) lining the trachea reducing a bird’s ability to clear harmful dust and bacteria from the respiratory tract. Additionally, it is not recommended to clean manure pits when birds are still present in a house as the process can release large amounts of ammonia into the environment.

2. Gastrointestinal tract

Coccidiosis, general enteritis, mycotoxins, antibiotics, poor water quality and abrupt feed changes all have the ability to disrupt the normal bacterial flora of the intestine. Pathogenic E. coli can invade the gut. When the mucosal barrier is disturbed, pathogenic ingestion of contaminated water, feed, and litter can serve as sources of E. coli.

Water should be routinely tested for coliforms, and the water lines should be treated with an approved product if high numbers of E. coli and other coliforms are found. Feed treatments (e.g. exposure to heat and formaldehyde) and organic acid products may reduce coliform bacteria levels in the feed.

3. Skin

Wounds and other breaks in the skin from scratches (due to overcrowding or old cages), rough handling by crews, ectoparasites or unhealed navels in chicks provide opportunity for pathogenic bacteria to enter the body.

4. Reproductive tract

Ascending infections travelling up the oviduct lead directly into the hen’s body cavity. Vent pecking and prolapse can lead to peritonitis.

Oviduct infection, respiratory disease and handling birds during late transfer (after the onset of egg production) can all result in yolks (or ova) laid outside the oviduct with the potentially developing into egg yolk peritonitis.

Additionally, high oestrogen levels are seen as hens enter and sustain peak production which increases the susceptibility of these birds to bacterial infection through suppression of the immune system.

5. Immune system

Healthy birds with functioning immune systems are remarkably resistant to naturally occurring E. coli exposure in the environment. Immunosuppression caused by early disease challenges (e.g. IBD, reovirus, CAV, Marek’s disease, adenovirus etc.) can increase flock susceptibility to secondary bacterial infection.

6. Omphalitis (yolk sac infection, navel ill, “mushy chick” disease)

Omphalitis, or inflammation of the navel (umbilicus), is one of the most common causes of mortality in chicks during the first week. Both E. coli and Enterococcus faecalis have been identified as the most common bacterial pathogens associated with first-week mortality (Olsen et al., 2012). Faecal contamination of eggs is considered to be the most important source of infection; however, bacteria can translocate from the chick’s gut or from the blood stream.

Infection with E. coli follows contamination of an unhealed navel and may also involve the yolk sac. Clinical signs of omphalitis include swelling, oedema, redness and scabbing of the navel area and/or yolk sac. In severe cases, the body wall and skin undergo lysis, causing the chicks to appear wet and dirty (i.e. “mushy chicks”). The incidence of omphalitis increases after hatching and declines after about six days (Nolan et al., 2013).

There is no specific treatment available for omphalitis in chicks. The disease is prevented by careful control of temperature, humidity and sanitation during incubation, processing and/or during chick transport (Kahn, 2010). Additionally, the hatcher should be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected between hatches.

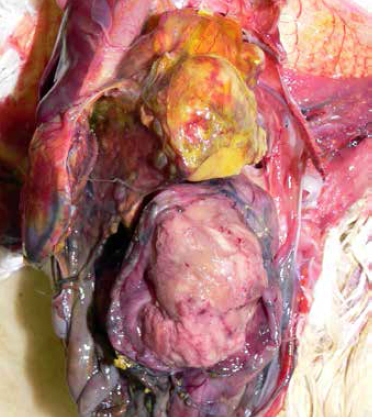

(Photo courtesy of Dr Robert Porter, Uni. of Minnesota)

Incubation Period

The time between infection and onset of clinical signs (the incubation period) usually varies between one to three days, depending on the specific type of disease produced by the E. coli bacteria.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs of colibacillosis can vary depending on the type of disease (local versus systemic).

Localised infections typically result in fewer and more mild clinical signs than systemic disease. Affected birds are usually under-sized, unthrifty and found along the edges of the house along walls or under feeders and waterers.

Severely affected birds such as those with colisepticaemia are often dull, lethargic and unresponsive when approached. Faecal material is often green with containing white-yellow urates due to anorexia and dehydration.

Dehydrated birds typically have dark dry skin which is more noticeable on shanks and feet.

Additionally, chicks and younger birds with omphalitis (navel/yolk sac infection) may have distended abdomens affecting mobility.

Post Mortem Lesions

Colibacillosis is diagonsed at necropsy; the gross lesions can include generalised polyserositis with various combinations of pericarditis, perihepatitis, air sacculitis and peritonitis (Bradbury, 2008).

Common postmortem findings in cases of colibacillosis include fibrin, yolk debris or milky fluid in the peritoneal cavity, in and around joints, and on the surfaces of multiple organs. In cases of peritonitis, there are accumulations of caseous (cheese-like) exudate in the body cavity resembling coagulated yolk material; this is commonly referred to as egg yolk peritonitis (Nolan et al., 2013).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of colibacillosis is based on isolation and identification of E. coli from lesions. Further testing can be performed to distinguish avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) from commensal E. coli isolates using molecular diagnostics such as PCR (Nolan et al., 2013).

Intervention Strategies

Management procedures

Effective control and prevention of colibacillosis depends on identifying and eliminating predisposing causes of the disease. Maintaining flock biosecurity is critical in the control and prevention. The goal is to reduce the level of E. coli exposure by improving biosecurity, sanitation, ventilation, nutrition and flock immunity.

| Management factors to control colibacillosis | |

| Biosecurity | Reduce exposure to E. coli and prevent introduction of other infectious agents Improve sanitation of environment (e.g. hatchery, house) Clean chick source Reduce faecal contamination of eggs, clean nest boxes and reduce number of floor eggs Treatment of feed with products to lower bacterial levels (e.g. pelleting, formaldehyde, organic acids) Collect dead birds more frequently |

| Nutrition | Feed additives that support healthy immune systems and improve survivability Proper protein ratios Increase selenium Increase vitamins A and E Probiotics to promote competitive exclusion |

| Ventilation | Improve air quality and ventilation to reduce dust and ammonia levels Minimise use of leaf blowers and mowers to reduce environmental spread |

| Immune system | Protect immune systems by preventing introduction of immunosuppressive diseases (e.g. IBD/Gumboro) and other bacterial and viral infections (e.g. IB, M. gallisepticum) Effective vaccination program matching vaccines to field strains Manage any respiratory vaccine reactions Maintain healthy gut flora (e.g. coccidiosis control) Routine serological surveillance Reduce stress (e.g. proper stocking density, no temperature extremes, etc.) |

| Surveillance | Monitor prevalence by routine posting of birds every few months Early diagnosis and treatment |

Treatment

Historically, antimicrobial drugs have been used to treat and control colibacillosis; however, the availability of effective antimicrobials has decreased due to threat of antimicrobial resistance and lack of new drug development in the poultry sector.

It is important to determine susceptibility of the bacterial isolate involved when selecting an antimicrobial therapy in order to avoid ineffective treatment and propagation of resistance profiles.

The following is a list of currently approved feed additive antimicrobial drugs available for treatment of colibacillosis in both pullets and layers. If there is high mortality due to E. coli infection, the live E. coli vaccine can be used as a treatment and is efficacious in 50 per cent of cases.

Consult a poultry veterinarian before commencing any treatment plan. Availability of drugs and local regulations may vary.

| Antimicrobial drugs available for treatment of colibacillosis in both pullets and layers | |||||||||||

| Drug | Route | Pullets | Breeders/Layers | Indications | Warning | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlortetracycline Aureomycin |

Feed | 200-400g/ton continuously for 7-14 days | 200-400g/ton continuously for 7-14 days | Control of chronic respiratory disease (CRD) and air sac infection caused by E.coli | No restrictions for use in laying hens | ||||||

| ditto | ditto | 500g/ton continuously for 5 days | 500g/ton continuously for 5 days | Reduction of mortality due to E.coli infections | ditto | ||||||

| Chlortetracycline Pennchlor |

Feed | 200-400g/ton continuously for 7-14 days | 200-400g/ton continuously for 7-14 days | Control of chronic respiratory disease (CRD) and air sac infection caused by E.coli | Do not feed to chickens producing eggs for human consumption | ||||||

| ditto | ditto | 500g/ton continuously for 5 days | 500g/ton continuously for 5 days | Reduction of mortality due to E.coli infections | ditto | ||||||

| Erythromycin Gallimycin PFC |

Water | ½g/gal of drinking water continuously for 5 days in pullets up to 16 weeks of age | ½g/gal of drinking water continuously for 5 days | To aid control of CRD associated with MG | Do not feed to chickens producing eggs for human consumption | ||||||

| Neomycin/Oxytetracycline NEO-OXY Neo-Terramycin Terraymcin Pennox |

Feed | 400g/ton continuously for 7-14 days | Do not use | Control of CRD & air sac infection caused by E.coli | Do not feed to chickens producing eggs for human consumption | ||||||

| ditto | ditto | 500g/tom continuously for 5 days | ditto | Control of CRD & air sac infection caused by E.coli | ditto | ||||||

| Tylosin Tylan Tylovet |

Feed | 1,000g/ton to chickens 0-5 days of age; follow with a second administration in feed for 24-48 hours at 3-5 weeks of age | 20-50g/ton feed continuously for 4-8 weeks | To aid control of CRD (associated with MG) | No restrictions for use in laying hens | ||||||

| Source: Feed Additive Compendium 2015 | |||||||||||

Vaccination

There are two main types of vaccines used in pullets and layers – inactivated and modified-live vaccines. Regardless of type of vaccine used, clinical disease attributable to E. coli infection tends to less severe in vaccinated compared to unvaccinated birds.

| E. coli vaccine types and characteristics | ||

| Type of vaccine | Description | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Autogenous inactivated (killed) |

Provides protection against homologous E. coli strains No cross protection Breast injection |

Reduced morbidity and mortality due to E. coli infection |

| Commercial modified- live |

Poulvac E. coli 078 (by Zoetis) Cross protection against serotypes O1, O2 and O18 Spray |

Reduced morbidity and mortality due to E. coli infection Enhanced bird productivity |

References

Bradbury, J.M. ed. Section 2. Bacterial Diseases: Enterobacteriaceae. Poultry Diseases. 6th edition. Saunders Elsevier, 2008.

Charlton, B.R. ed. Avian Disease Manual. 6th edition. Athens: American Association of Avian Pathologists (AAAP), 2006.

Kahn, C.M. ed. The Merck Veterinary Manual. 10th edition. Whitehouse Station: Merck & Co., Inc., 2010.

Lundeen, T. ed. Feed Additive Compendium. Bloomington: Penton Farm Progress, 2015.

Nolan, L. et al. Chapter 18: Colibacillosis. Diseases of Poultry. 13th edition. Ames: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

Olsen, R.H. et al. An investigation on first-week mortality in layers. Avian Diseases. 2012; 56:51-57.

February 2015