Farming through the years: adapting to the world we live in

Prior to plant cultivation, humans were hunters and gatherers. Agriculture’s origins go back thousands of years, with evidence from Mozambique pointing to grass-seed being part of humans’ diets as far back as 105,000 years ago, during the Middle Stone Age.Wild grains were among the first items to be gathered, but the practice of planting them for food is believed to have started around 12,000 years ago, with a variety of crops including peas, lentils, and barley. It was centuries later before farming became a full-time practice. Much later again, the 20th century brought about rapid change in the agricultural sector, with industrial agriculture becoming the most common mode of farming.

While the general public may take farming for granted, for generations farmers have been striving to implement the best methods, not only to speed up agricultural processes and increase yields but also to ensure farming remains a profitable enterprise, so they can continue to make a living from growing food. Through the years it is not only the kinds of produced favoured by farmers that have changed, but the methods of farming too. With the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic giving rise to concerns over food supplies, we explore some key changes in farming, including poultry’s return to the top table of meat consumption, and how the agricultural landscape has transformed over the last 100 years.

One hundred years ago

In the UK, the National Farmers’ Union was officially formed in 1908 to represent the interests of farmers, but it wasn’t until 1917 that the first major piece of legislation it lobbied for came into effect. The Corn Production Act, which guaranteed British farmers a good price for their crop, was followed up by the 1920 Agriculture Act, designed to support price guarantees for agricultural products and to maintain minimum wages for farm labourers.

After World War I, British agriculture saw a crash in wheat prices, as prices slumped from 84 shillings (s) and 7 pence (d) to just 44s 7d in a year. Both acts were later repealed in what many saw as the government’s “Great Betrayal”.

The removal of price protections resulted in a free-market economy, and by 1922 almost a quarter of all British land had changed hands. A depression was felt across the sector as wheat acreage halved and land remained untenanted. The dark days of 1920s farming came to an end with the British government promising investment — the innovations that followed put farming on a very course for the subsequent 100 years.

Machinery

A demand for machines during the 1960s brought about a monumental change in farming practices, and leading to a 30-year period of drastic changes to farming practices.

All broiler farmers know that a chicken house and incubator have long been essential elements of a successful poultry business. But now, transformative technology is primed to alter how the poultry industry, which is one of the fastest-growing meat-production sectors in the world, will operate in the future. At the inaugural Poultry Tech Summit, held in Atlanta in 2018, poultry-house-patrolling robots and rust-proof gearboxes for processing plants were the talk of the event.

It is envisaged that by 2025 the top 20 to 30 percent of poultry farmers will use robots to aid their processes – and the innovative ChickenBoy could be a market leader. The robot can run on simple rails to monitor management issues in chicken houses, from the detection of dead birds to bedding problems and the measurement of ambient conditions.

Meat production

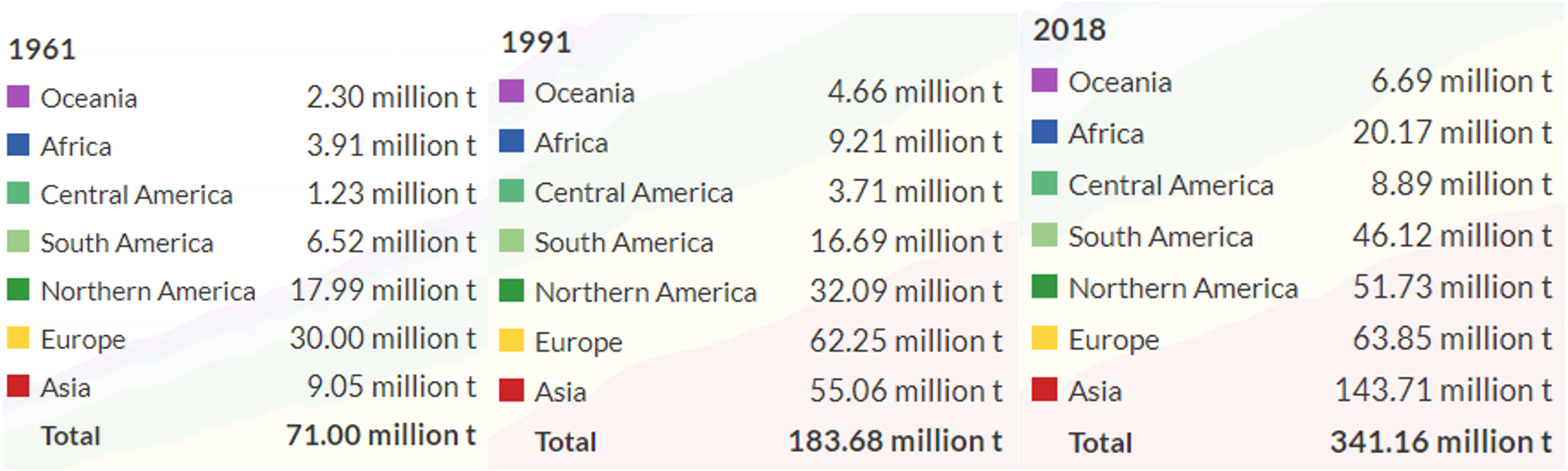

The rise in demand for meat – including cattle, poultry, sheep, goat, pigmeat and wild game – has seen meat production increase nearly five-fold in 50 years, from 71 million tonnes in 1961 to 341.16 million tonnes in 2018. Although Asia had been the third-largest producer at the start of the 1960s, it now produces more than double the quantity of meat than its nearest continental rival, Europe, which harvests just 63.85 million tonnes compared to Asia’s 143.71 million tonnes.

© Our World in Data

China’s dominance of the market is underlined by the fact it produced 40 times more meat than the UK in 2018. Boosted by its strong economic growth, China has also seen a 15-fold increase in consumption of meat, more than any other country. However, the United States has overtaken Australia as the largest consumer of meat, with the average American citizen eating 97.1kg of meat per year.

Poultry has become one of the most farmed meats in modern times, with production rising from just 12 percent in 1961, to 35 percent in 2018 – second only to pigmeat, which accounts for 35 to 40 percent globally. Earlier this month, it was reported that the number of industrial-sized pig and poultry farms in the UK has risen by 7 percent in the last three years, to 1,786 units.

The rise of technology

In the 1940s there was a total of around 5 million animals on UK farms, but this had dropped to just over 500,000 by the end of the 1960s. In recent decades, though, the market has expanded rapidly, and this has brought about new technologies.

A good example of the kind of innovation the industry has seen in recent years is the Little Bird FeedCast system, which estimates the amount of feed in on-farm bins. To do this it uses a small device to apply vibrations to the bin surface, while sensors assess the volume beneath. The units, which are solar-powered, report feed levels through a mobile app and web portals that are accessed by growers, feed mills and integrators. The system provides projections and helps to reduce – or even eliminate – feed outages.

Looking to the future

With climate change dominating headlines across the globe, farming contributes to 10 percent of the UK’s emissions. Although the sector has been criticised in the past for a failure to tackle pollution, one of the major focuses for future development is improving the fuel efficiency of machinery within the meat and daily industries. Other priorities, meanwhile, include developing cleaner fertilisers and better animal-welfare management.

The National Farmers’ Union has set a target to reduce British agriculture’s carbon footprint, while working to offset carbon emissions by 2040. Improving productive efficiency and land management, and changing land use to capture more carbon, are just some of the measures the NFU are supporting across England and Wales. The organisation will also encourage members to capture methane to repurpose for heating people’s homes and alter the diets of cattle and sheep.

With climate change at the forefront of all farmers’ minds, and heat stress having knock-on implications for the poultry industry, broilers are looking at ways to improve ventilation in chicken houses. A study in Nigeria found that farmers were adapting eight strategies to counter rising summer temperatures – including air ventilation, energy-efficient bulbs and the use of vitamins to aid thermoregulation in birds. Water sprinklers and cooling pads have also been shown to be useful.

Across the world, farming continues to transform, and transform at speed. The last 100 years have seen major alterations through streamlined practices, changing consumption habits and the rise of technology. It’s impossible to predict what transformations the next century will bring – but agriculture’s history of innovation suggests it will rise to the challenge of feeding an ever-changing world.