Has Brazil recovered from Operation Carne Fraca?

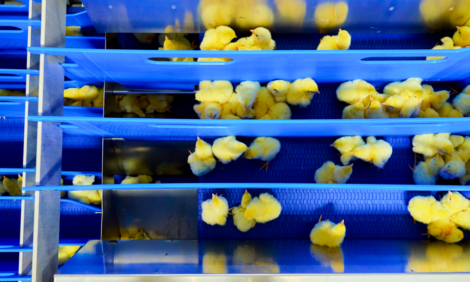

After the biggest corruption scandal in its history, the Brazilian meat industry is still feeling the shockwaves. But what is the real cost of Operation Carne Fraca to Brazil’s economy and the global trade in poultry meat products?The Brazilian meat industry suffered a huge hit after Brazil’s federal police made public “Operation Carne Fraca” (known as “Weak Flesh” in English language media) on 17 March 2017. This co-ordinated action was the culmination of a two-year investigation that had revealed a complex corruption scheme within the Brazilian meat-production sector, in which health inspectors and politicians were bribed to approve the sale and export of meat unfit for human consumption. The accusations include: misrepresenting products’ nutritional values failing to meet hygiene standards in slaughterhouses; repackaging of out-of-date meat; tampering with the meat’s colour and smell with acid and potentially carcinogenic chemical substances; and the overuse of harmful additives.

This was one of the largest police operations in Brazil’s recent history, in which more than 30 companies face criminal charges, accused of multiple illegal practices. The day the operation was launched, the federal police sent out more than 300 warrants. Two of the world’s largest meat producers and exporters, BRF and JBS, were among the corporations implicated in the scandal. It was said that these two companies had representatives influencing the selection of inspectors overseeing their plants and had bribed them to approve inadequate products. Following the police’s announcement, JBS and BRF shares have fallen by 10 percent and 8 percent respectively on the São Paulo stock exchange.

Brazil is the world’s largest beef and chicken exporter, with agribusiness representing 48 percent of its global export trade. This means that Carne Fraca has caused disruption on a worldwide scale regardless of the attempts of the Brazilian ministry of agriculture to ease the situation by claiming the investigation revealed isolated cases which did not typify the whole national meat industry. The export of Brazilian meat rapidly dropped from a daily flow of US$60 million to US$74,000 once the operation had been made public.

The trade balance, and consequently the country’s economy, had a worrisome period during March and April with a decline of 25 percent in the meat export numbers. By the end of March 2017, 20 markets had completely suspended imports of Brazilian meat and more than 40 introduced partial bans. China, the European Union, Chile and South Korea, which together consume a third of the Brazilian meat sold abroad, said they would ban some or all imports from Brazil until the country could allay misgivings about its inspection regime. Hong Kong not only suspended imports but also ordered meat products to be removed from the local market, and the United States of America vetoed the imports of in natura (ie non-processed) meat – a trade that was negotiated for 17 years and only recently approved.

In response to the Carne Fraca operation, several American, Asian and European countries have demanded changes, such as microbiological checks on meat before shipping as well as sanitary adjustments in production and storage facilities. In order to comply with such requests and to tackle the industry’s loss of credibility, the Brazilian government declared that quality standards had been set higher and fines ranging from US$4,500 to US$150,000 were threatened for those who failed to comply. A new lab for investigation on animal pathogens was opened and stricter rules were imposed on the inspection sector. In addition, political nominations to the ministry of agriculture’s state superintendencies were halted, to avoid any further corruption cases. In spite of the government’s guarantees that these new regulations would be implemented, a month-long audit of Brazilian slaughterhouses carried out in April 2017 by an EU team of experts revealed negative results, and the EU thereafter required new measures and further tightened control on Brazilian meat imports.

Surprisingly, two months after the meat scandal went public, overseas meat sales showed signs of recovery from a significant recession, and sales have picked up as some countries have lifted their embargos. According to the Brazilian Association of Animal Protein, three months after the scandal broke, poultry meat exports were still 10 percent below that of June 2016, and the year-to-date exports volume until September 2017 was 2.1 percent lower than that of the previous year for the same period. However, exports to South Africa, the UAE, Qatar and Mexico contributed to the recovery of monthly sales, with a slight increase from 386,900 to 387,500 metric tonnes of poultry meat between September 2016 and September 2017. By October 2017, and despite the lower prices per tonne, profit from chicken sales showed a very positive growth.

At the end of October 2017, the Brazilian agriculture minister Blairo Maggi pledged that all losses due to the Carne Fraca operation had already been restored, and that the sanitary conditions and its supervision were continuously improving. He further claimed that no infringements had been found by the countries that were maintaining their inspections of Brazilian meat products, and only an insignificant part of the importing markets was still enforcing an embargo.

In spite of this unexpected recuperation, some recent events suggested that this scandal is still far from being forgotten. Michel Miraillet, the new French ambassador in Brazil, underlined that his country would hinder the ongoing negotiations for a free-trade agreement between the EU and the South American trading bloc Mercosur based on the Carne Fraca revelations. This allegation was supported by the latest European Commission’s Food and Veterinary Office report, which, as stated by the Irish Farmers’ Association president Joe Healy, “completely undermines any credibility to the arguments being made in the Mercosur trade negotiations that Brazil will ever meet EU production standards on meat imports”.

Nevertheless, new markets are stepping forward. For instance, in November 2017 Saudi Arabia declared its interest in increasing the imports from Brazil. Moreover, BRF, which used to account for 14 percent of the global poultry market and exported to 120 different countries, announced that one of its factories had reopened by January 2018 and will focus its production on the halal market for the Middle East.

It was forecasted that the global poultry-meat yield would increase by 1.2 percent in 2018 to a total of 91 million tonnes, a seventh of which would be supplied by Brazilian producers. Although it seems that the Carne Fraca operation is still haunting the reliability of Brazilian products in the external market, Brazil doesn’t seem to have lost its place in the world’s meat industry.