Intestinal health and pigmentation of broiler chickens

In some countries, Mexico in particular, but also in others such as China, the Philippines, Peru, certain regions of Spain, etc., the colouring of the skin of broilers is an important factor when consumers choose the bird that they want to buy, as they directly associate yellow and/or golden tones with good quality, fresh and healthy chickens. In this article we analyse the effect that different factors can have on pigmentation in chickens.The cost in raw materials of achieving this pigmentation is considerable (it accounts for between 8 and 10 percent of the total feed costs), varying according to the intensity of the final tone that is aimed for (which is very different depending on the customs of each country). If the required values are not reached and/or there is a lack of uniformity, this normally incurs financial penalties in terms of the price of meat per kg when it is placed on the market.

This colouring is obtained by the combination of xanthophylls which produce yellow colours (lutein, zeaxanthin and cryptoxanthin) and, in some regions, reds (capsanthin and/or canthaxanthin), which together can produce a golden colour with a natural-looking appearance. Pigmentation is an incremental process, with the colouring cycle lasting approximately 2-3 weeks. These pigmenting substances can be of natural origin, as they are present in maize, corn gluten meal, alfalfa, calendula, etc. Or synthetic pigments can also be used, which provide colour more quickly, although the cost is higher. The mixture of different pigmenting ingredients depends on the market for which the birds are intended, as well as the availability and price of the pigments.

Pigment is absorbed via the ciliary epithelium of the midgut and, for this to take place properly, a process of enzymatic hydrolysis of the xanthophylls, present in the diet in the form of fatty acid esters, has to occur. Of course, this requires a very good state of health of the intestinal mucosa, which must be free of conditions such as bacterial enteritis or damage caused by avian coccidiosis.

There are many other factors that can affect the absorption of pigments, as well as those relating to the diet itself (concentration, type and combination of xanthophylls; interaction of the xanthophylls with other ingredients, especially fats; toxic factors such as mycotoxins, etc.): feeding programmes, installations (Brown-out systems show lower levels of pigmentation), genetic line (some have limited or no capacity to achieve saturation levels of pigment), sex (females acquire pigment better than males) and diseases, not only those that reduce feed consumption (and therefore ingestion of xanthophylls), but also, as mentioned earlier, those which can cause intestinal damage (coccidiosis, bacterial enteritis, etc.), as the absorption of xanthophylls is directly linked to intestinal health and integrity (Ortega et al, 2012).

Speaking specifically about avian coccidiosis

As we have already mentioned, avian coccidiosis is one of the most important factors that can affect pigmentation, with reductions of up to 90 percent in serum levels of lutein having been observed as a consequence of the disease. And, more specifically, the species involved are Eimeria acervulina, E. praecox, E. mitis and E. maxima, as they cause desquamation and shortening of the villi of the intestinal mucosa and parasitise the sites of greatest pigment absorption in the intestine of the birds. Furthermore, Eimeria maxima is the principal predisposing factor to another important disease that can affect intestinal integrity and the absorption of pigment, necrotic enteritis caused by the bacterium Clostridium perfringens (Williams, 2005).

This is why it is essential to obtain a good level of protection if we want to avoid the lesions and consequences of coccidiosis in chickens and achieve the desired parameters in terms of pigmentation. The most widely used method for the control of Eimeria spp. is the use of coccidiostats in the feed. However, the addition of these is becoming more and more restricted around the world for reasons of demedicalisation and, furthermore, with the consecutive and prolonged use for many years of a limited number of active coccidiostat ingredients, the appearance of strains of the parasite that are resistant to their action has been increasing; this means that more and more problems are being seen in birds treated with coccidiostats, which are showing pigmentation deficiencies, a consequence of subclinical coccidiosis and subsequent deterioration of intestinal health.

As the main alternative, the use of live attenuated vaccines against coccidiosis has been shown to be a very effective option for the prevention of coccidiosis, both in developing immunity against the disease and replacing the field strains which are resistant to coccidiostats with their own vaccinal strains (Ronsmans et al, 2015).

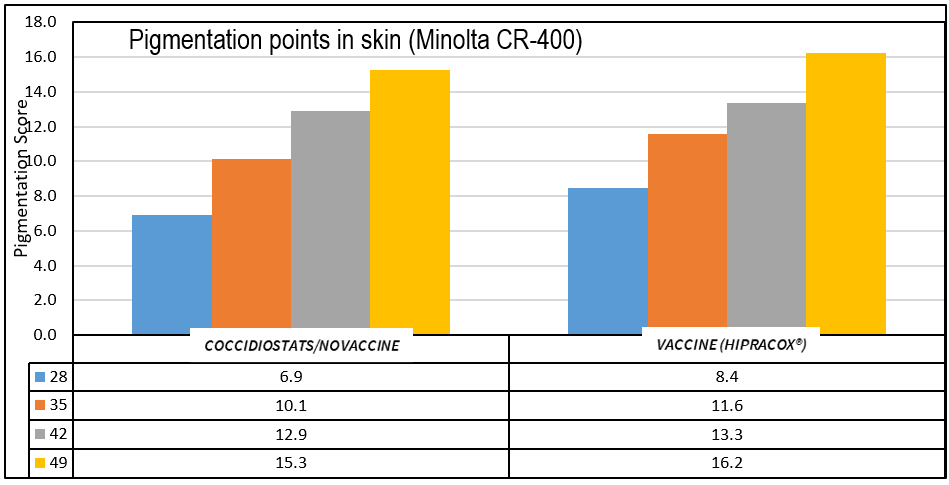

The graph below shows the improvement in the level of pigmentation achieved in chickens with the use of a coccidiosis vaccine attenuated by precociousness, compared with the records of birds treated with coccidiostats in previous years.

| References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ortega, STJ, Ortiz, MA, Carmona, MM, | ||||

| (2012) | Evaluación de parámetros productivos en pollo de engorda en función de la integridad intestinal e inmunidad en el aparato digestivo.. Memorias 5a Reunión AECACEM. Marzo 2012. | Pag. 250-254. | ||

| Pérez – Vendrell A.M., Hernández J.M., Llauradó L., Schierle J y Brufau J, | ||||

| (2001) | Influence of Source and Ratio of Xanthophyll Pigments on Broiler Chicken Pigmentation and Performace.. Poultry Science 80. | |||

| Ronsmans, S.; Van Erum, J.; Dardi, M. | ||||

| (2015a.) | The use of a live coccidiosis vaccine in rotation with anticoccidial feed additives: results from the Belgian field.. Proceedings of the XIX World Veterinary Poultry Association Congress. Cape Town, South Africa, | 876-880. | ||

| Williams R.B., | ||||

| (2005.) | Intercurrent coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis of chickens: rational, integrated disease management by maintenance of gut integrity.. Avian Pathology | 34 (3), 159-180. |