Is precision poultry production possible?

Meet the Swiss researchers whose innovative approach to movement technology is allowing data-led farming to zoom in on the individual bird.In recent years, the biggest buzzword in agriculture has been “precision”. While precision agriculture made its debut decades ago in crop production, where GPS technology has helped farmers reduce the use of herbicides, pesticides and fertilisers, it has only recently made its way into the livestock sector.

At the level of the individual animal, beef, dairy and pork producers use wearable sensors to catch disease earlier and improve welfare and comfort. They also use sensors to detect changes in body temperature and pH, to analyse sound and to track movement and behavioural changes. The technology’s transition into the poultry sector, however, has been slow, and there are currently no off-the-shelf products for tracking individual behaviour in poultry. But there may be value in doing so. Swiss researchers are evaluating different types of systems - including infrared and radio-frequency identification (RFID) tagging technology - to track individual behaviour in layer hens. They hope that the data they collect will further improve housing and welfare.

Led by Michael Toscano, poultry welfare researchers from the Center for Proper Housing, Poultry and Rabbits (ZTHZ) in Switzerland are trying to better understand hen behaviour through research at the individual level. ZTHZ, which is a collaborative effort between the University of Bern and Switzerland’s Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office, uses two layer houses for its on-site research. The first houses eight groups of 360 hens and has a winter garden and pasture. The second houses 20 groups of 225 hens and has an outside area with a winter garden. The facilities allow researchers to replicate trials and conduct research in a semi-commercial setting.

In a typical day, hens in open aviary systems will make their way down from elevated positions where they were sleeping to the litter area about 20 minutes after the lights come on in the wee hours of the morning. They’ll spend some three to four hours scratching, pecking and dust bathing before heading to the nest box, most likely to lay an egg. From there, they’ll wander around, and move outdoors to the winter garden when the pop hole eventually opens. On the surface it may appear as if the birds move randomly or without structure, but when tracked individually, unique behaviour becomes apparent. Some, for instance, make their way to the outdoors the minute the pop hole opens. Others barely venture outside at all.

The use of precision technology in dairy production has increased enormously. “It works really well at an individual level because a dairy cow is worth so much money relative to a laying hen,” says Toscano. “If you can figure out that your dairy cow is lame very early on, you’re going to save yourself a lot of money.

“But with chickens, if you’ve got 30,000 birds, an individual bird is not really worth that much,” he continues, “so there hasn’t really been that much research in the area.”

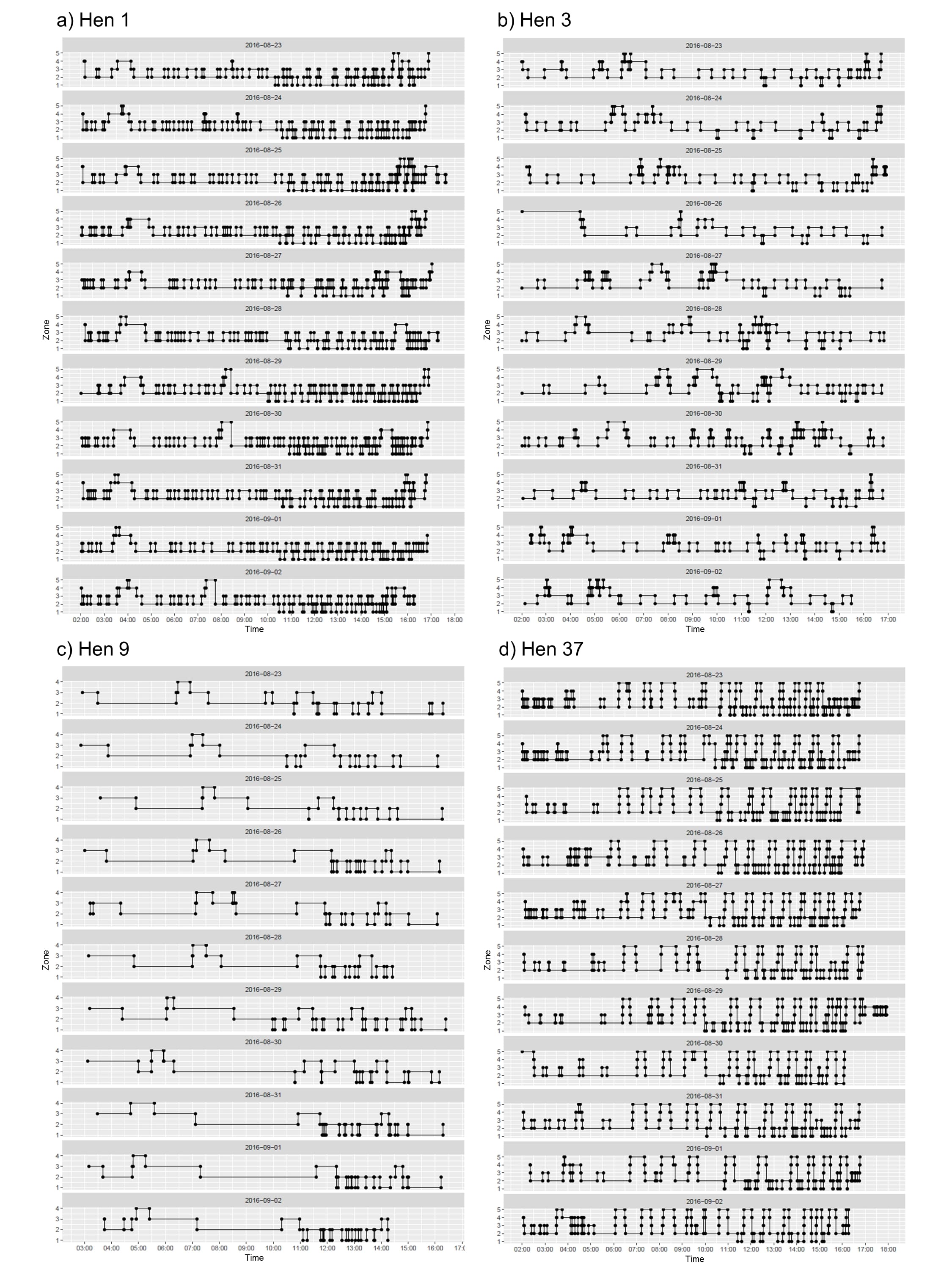

At ZTHZ, however, Toscano is able to monitor birds using an infrared tracking system designed by on-site technician Markus Schwab. The tracking system uses beams of infrared light that have special codes embedded in them, similar to the beams emitted by your television remote control. Emitters, which are attached to the wall, create beams in the areas where the researchers want to record hen movement. Receivers are attached to the hens’ legs. They recognise the codes in the infrared beams and store information each time the hen enters and leaves a zone (the battery in the receiver lasts up to three weeks). Using this system, researchers track movement in five areas of the barn. The output for four individual hens over 11 consecutive days can be seen in Figure 1.

While the system design is quite simple, Schwab admits the harsh conditions in the barn were challenging for the equipment. Both the emitters and the receivers had to be protected from dust, faeces, mites and curious hens that would peck at the equipment.

“To make the system work in these conditions, I had to put all emitters in a small protective box with an acrylic glass cover,” says Schwab. “To make the equipment easy to install, I soldered plugs on the box to make changing fast and simple.

“I also had to find a way to protect the receiver that was worn by the bird,” he continues. “For this I used a small transparent plastic container. This protected it also from dust, faeces and mites.”

Once Toscano put the information into a graph, he noticed something interesting. The data revealed that not only does the flock have a specific pattern, but many individual birds also have set daily routines. This piqued Toscano’s interest and he began thinking of more questions that one could answer by studying birds on the individual level.

For instance, while the researchers can see when the birds have gone up to the nest-box area, they currently can’t tell whether they have laid an egg. It also seems there are some birds that visit the nest box irregularly or not at all. Knowing this type of information could help breeders to select “good layers” over those birds that consistently lay on the floor or somewhere outside of the nest-box area.

“My system could be quite beneficial for a breeding company because now they could have traits that they could breed for that they couldn’t actually identify previously,” says Toscano. “Before they weren’t able to go into a 50,000-bird flock and actually identify the genetic traits that are operating at that level.

“You want good egg-laying behaviour,” he continues. “You want birds that are laying in the nest box, and it would be really interesting to figure out what’s causing that variation.”

Another trait Toscano would like to quantify is feed efficiency: how much feed a bird consumes versus how many eggs it lays.

In terms of hen welfare, Toscano is interested in learning more about feather peckers and their motivations. “Where flocks have access to a range, the flock tends to have less feather pecking,” he says. “Now whether that’s because birds that are feather peckers go outside more or whether birds that would be feather pecked are going outside to get away, we don’t know.”

Knowing more about which birds cause problems would allow breeders to eliminate that trait through their breeding programmes. “If we can identify certain traits that are linked to economic importance then that’s going to be helpful to the breeding programmes,” says Toscano.

Another observation Toscano made in the course of his study was that while 97 percent of the birds did go outside, most never went beyond the winter garden to the range area. “Even though they could go onto the range, they seemed to spend the majority of their time in the winter garden,” says Toscano.

Winter gardens are outdoor spaces that are enclosed on all sides. Typically, they have a roof and are surrounded by mesh fencing. Birds have access to fresh air and sunlight but are protected from predators. Knowing how many birds use the winter garden versus the range area is valuable information for retailers and consumers who might be pushing producers into offering space to birds that aren’t interested in using it.

Toscano and his team made another interesting observation using individual data. Following a standard vaccination, hen movement was suddenly extremely variable, a behavioural change that seemed to last seven to eight days. Says Toscano: “It would be really interesting to look at this and say: well, if we can pick up these patterns and changes, how long do they last? How long does it take some of the birds to settle? What are the long-term impacts of these interventions on the birds’ productivity?”

While the infrared system offered a good starting point, a new tracking system based on radio frequency would allow the researchers to track movement in all types of commercial systems, not just the special facilities in Switzerland. Schwab is working on the RFID tracking system now.

“I have to find a way to fix the tracker on the hen, so they do not get disturbed too much,” says Schwab. “But we think the system has lots of potential.”

Researchers aren’t the only ones intrigued by the possibility of observing individual hen behaviour. American egg producer John Brunnquell, president and founder of Egg Innovations, a unique poultry business based in Warsaw, Indiana, is working with Toscano to explore its potential. Brunnquell would like to use the RFID tracking system on 5 percent of his flock, using them as sentinel birds to learn more about overall behaviour and to detect problems earlier.

.jpg)

Brunnquell owns 65 layer operations each with flocks of 20,000, contracted out to farmers in the region. All 65 barns are identical in their layout, which makes them perfect for replicated research. Brunnquell believes that more precise flock knowledge will lead to a more precise management strategy. “Does it alter the way we design a nest?” he asks. “Does it alter the enrichments in the pasture? For me, it’s all about optimisation. If I’m already producing at 102 percent of what the genetics say they can do, how do I get it to 104 percent?”

“I believe with this individual knowledge what intuitively it will lead to is me modifying - not changing, but modifying - barn layout,” he says.

Hens raised under the Egg Innovations label produce free-range and pasture-raised eggs. But the reality is that some of Brunnquell’s birds never go outside. Knowing more about where the birds go and why would help him to modify the barn to better meet their needs. For instance, should he change the wavelength of the light in the barn to make up for the outdoor daylight those birds are missing out on?

Most importantly, though, Brunnquell believes a monitoring system would allow him to detect disease quicker. “What if we gave them some type of sensor mounted on the bird - either a necklace or a backpack - and it identified diseases two to three days early because of individuality?” he asks. “Now that would be something for the commercial marketplace. I would buy it.”

In addition to Toscano and Schwab, the Bern based team also includes: John Berezowski, Christina Rufener, Yandy Abreu, Filipe Maximiano Sousa and Bernhard Völkl, as well as Lucy Asher of Newcastle University