Management of Coccidiosis Vaccination: First Critical Weeks

Coccidiosis immunity is developed through multiple exposures to the Eimeria parasite antigens, writes Linnea Newman, DVM.Unlike viral vaccines, coccidiosis vaccines are ‘self-boosting’: they recycle under the correct field conditions. It is critical that coccidiosis-vaccinated birds continue to have access to their faeces containing shed oocysts until immunity is complete.

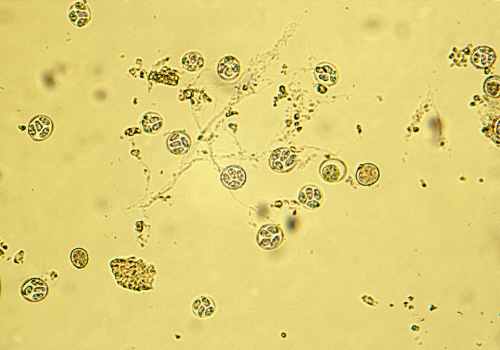

When chicks ingest a coccidiosis vaccine, the sporulated oocysts break open and the parasites will infect the intestinal cells, completing multiple stages of the Eimeria life cycle. After this initial life cycle, new oocysts are shed into the litter.

To achieve immunity, the oocysts must become infective by sporulating in the litter, and the birds must ingest them to initiate the next life cycle. A third and sometimes a fourth or fifth life cycle must be completed to induce fully protective immunity against all Eimeria species.

Several factors interact under field conditions to speed or slow the onset of immunity.

1. Sporulation

The newly shed oocysts must sporulate to become infective. This process requires oxygen, warmth and humidity. Usually, there is sufficient oxygen and warmth in a poultry house, but humidity can become a problem where the environmental relative humidity is very low or where the bird density is low, resulting in less faecal moisture in the litter. Relative humidity of about 70 per cent is recommended.

Sporulated oocysts

2. Oocyst output

Technically, we might be able to achieve immunity by gavaging (direct oesophageal application) only 10 sporulated oocysts twice per week for 2-3 weeks. But under field conditions, 25,000 birds in a broiler house must be able to consume enough fully sporulated oocysts to initiate a secondary infection, and they must do it at approximately the same time. This requires access to many oocysts.

If we introduce too few oocysts with the initial vaccination, the oocyst output will be low. In this case, it could take days for each bird in the house to find an infectious dose from the litter. If the litter is dry, and sporulation rate is low, it can take even longer.

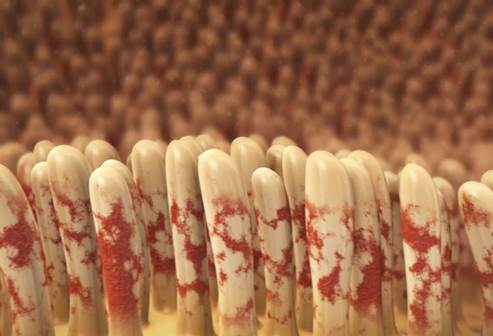

If it takes too long, some naïve birds remain in the house when others have already begun to shed oocysts from the second life cycle. Then the naïve birds may become exposed to an extra high dose of vaccine oocysts or they may become exposed to wild strains, resulting in clinical coccidiosis.

Intestinal villi damaged by coccidia

3. Bird density

High bird density means that many oocysts will be shed into a given area, and more faecal moisture results in higher sporulation rates. High bird density promotes rapid exposure of the entire flock to coccidial oocysts.

Very high density may also mean a very heavy exposure to oocysts, potentially resulting in intestinal pathology and negative performance consequences.

Conversely, very low density means that it will be difficult for every bird to develop uniform exposure and immunity. Replacement pullets are often placed at lower density. This can sometimes result in slower and less uniform onset of immunity.

In general, non-attenuated vaccines require 0.5 square feet per bird or 21 birds per square metre for the first seven days to initiate the second life cycle after hatchery vaccination. After that, spreading the birds out to at least 0.65 square feet per bird or 16.5 birds per square metre is recommended to avoid excessive moisture and excessive oocyst exposure.

It is important for all components of recycling to be balanced: environmental conditions for sporulation, oocyst output and bird stocking density. This ensures rapid and uniform development of immunity with coccidiosis vaccine.