Managing fully beaked flocks

Due to changes in customer sentiment, restrictions on beak treatment practices have been introduced in some countries and are being considered by many others. Full (untreated) beaks are obligatory in European Union organic flocks, and this practice is being voluntarily extended to more barn and free range flocks on a customer by customer basis.

Management of fully beaked flocks requires more consideration and input relative to beak-treated flocks. The following document outlines areas which should be considered by farm managers, nutritionists, and health professionals.

There are key factors to consider in managing fully beaked flocks.

- Pullet quality

- Lighting

- Ventilation

- Environment

- Feeding system management

- Nutrition and diet nutrient specifications

Pullet quality

The goal for rearing flocks with full beaks is to transfer the hens with excellent feather cover, good behavioral attributes, good body weight, and high body weight uniformity with good overall body condition. The better overall condition a pullet flock is going into transfer, the better its behavior and feather condition will be throughout the lay period.

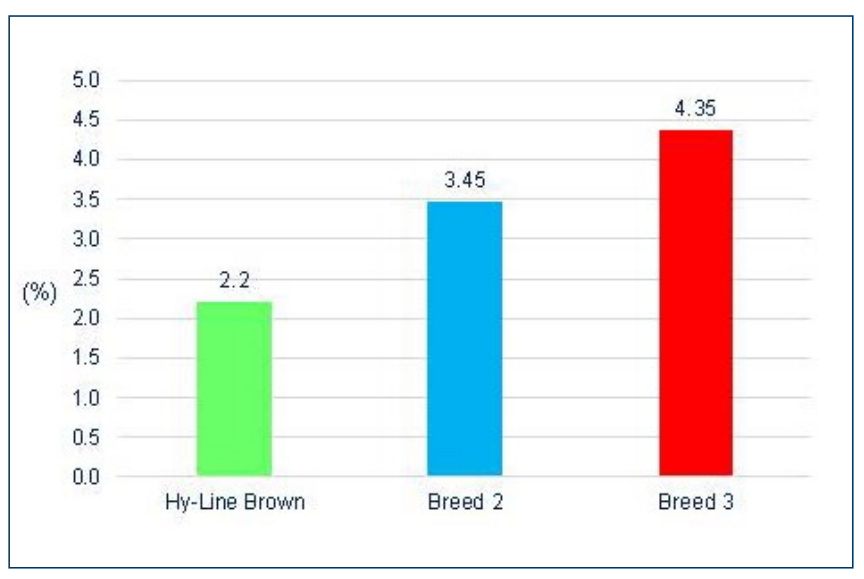

While management is a critical component of success for fully beaked flocks, genetics also plays a role. Hy-Line varieties have been bred to be particularly calm, sociable, and tend not to express aggressive behavior during stress events. In a recent set of both internal and university studies1,2 assessing the performance of non-beak-treated flocks, Hy-Line Brown resulted in significantly lower mortality relative to other breeds (Figure 1).

Rearing can have a significant impact on the behavior of the birds later in life. Sociable birds in rear tend to stay sociable in the laying period, while those flocks that exhibit anti-social behavior in rear tend to maintain this behavior in lay.

Factors contributing to good flock behavior:

- Uniformity: Good uniformity will correspond with better flock cohesion and behavior.

- Feather cover: A poorly feathered bird at point of lay is more prone to stress during the laying period. Factors that contribute to feather quality include proper growth, nutrition, disease, management, overall stress, and uniformity. Pullets undergo three molts to transition from chick down to adult feather cover. To achieve the best feathering, the pullets must be healthy and free of stress for the duration of feather growth.

- Environmental conditioning: Hens that are less excitable due to external stimuli will be less stressed and more sociable.

Rearing Recommendations:

- Ensure there is adequate provision of litter at all times through rear. An inadequate amount of litter in rear can result in feather pecking behavior later in lay.

- Condition pullets in rear to audio and visual stimuli. Mechanical noises such as initiating the feeding system is a good way to condition the bird to spontaneous noise. Use of a radio in the rearing house will familiarize birds to sounds. Flock managers should walk frequently inside the house among the birds to accustom them to human contact. Changing the color of clothes and footwear frequently will also help condition birds to visual stimuli.

- Adapt rearing birds to the equipment and furniture used in the laying house. Provide adequate perches/slats in the rearing house and use the same feeding system as that used in the laying house. Chain feeding systems are often used in free range and aviary systems as they are associated with less feed selection and wastage, so introduction of this system in the rearing house aids familiarization.

- Enrich the bird’s environment with perches, elevated platforms with feed and water, foraging material, pecking blocks and dust baths. These enrichments can prevent feather pecking and should be introduced at an early age (Figure 2).

- Stock birds at recommended rates to provide sufficient feeder, drinker, and floor space to minimize social stress.

- Achieve optimal body weight, conditioning, and uniformity by the end of the rearing period. Body weights should ideally be 100–150 g above the breed recommendation at 18 weeks with 85% uniformity.

Lighting

The pullet lighting program is essential in supporting overall body weight and feather growth in rear. There are three main components to any lighting program: the initial step-down, the constant period, and the stimulation.

Intermittent Lighting and Step-Down

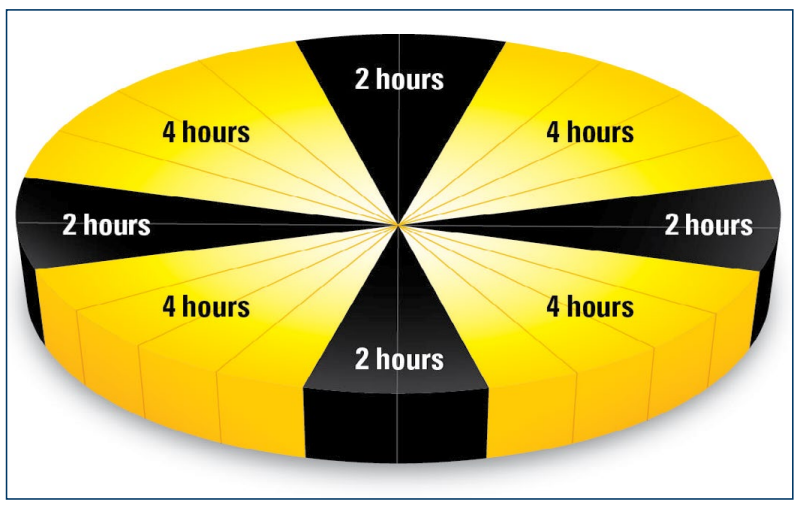

An intermittent lighting program for chicks should be used from 0–2 weeks of age. This program provides (Figure 3) cycling of light and dark periods, which provides the chicks periods of rest throughout each 24-hour period. The resting and activity behaviors of the flock are synchronized.

As chicks have not yet developed a circadian (24-hour) rhythm, the intermittent program can be modified to fit the farm’s work schedule. The recommendation is to provide between 3 and 6 dark periods, ranging from 1 to 2 hours each, which can be adapted for flocks exposed to natural light during the day.

Light intensity from 0–3 days of age should be 40–50 lux, reduced to 25 lux by the end of the intermittent lighting program. Reduce intensity to 10–15 lux no later than 4 weeks of age and continue until up to 2 weeks prior to stimulation.

Lighting must be LED and flicker-free to minimize

stress:

- 3000–5000 Kelvins in rear

- 2700–3000 Kelvins in lay

After the conclusion of the intermittent lighting, provide 18 hours of constant light with 6 hours of dark and start the step-down portion of the lighting program. Utilize a slow step-down program to reach 10–12 hours day length by 10 to 12 weeks of age.

Constant Lighting Period

- Day length: Consistent day length starting at 10 or 12 weeks until stimulation. The duration of consistent day length is predicated on the history of the farm, season, and the time of natural light that will be present by 16 weeks of age. A longer consistent day length will allow for more feeding opportunities and will enhance growth if needed for warm weather or challenging conditions. The body weight goal for fully beaked flocks is at least 5% above standard. If birds are not 5% above target by 8 weeks of age, adjust the lighting program to allow for a longer consistent day length. Ensure the period of consistent day length is a minimum of 3 weeks after the step-down is complete.

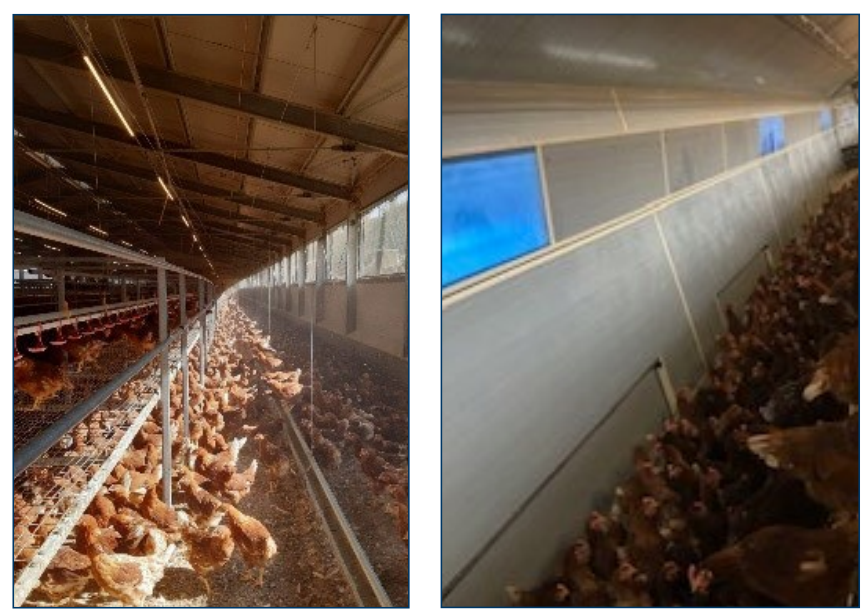

- Lighting type and intensity: To limit the stress at transfer, match the lighting programs (duration and intensity) and type of lighting (e.g. LED) in both rear and lay houses. Maintain the same light intensity for the first 3–4 days after transfer to allow the birds time to adapt to the new environment. After this period, implement the laying lighting program. Exposure to some natural lighting in the rearing house can help to customize birds to natural lighting if this is stipulated in the laying house (Figure 4.)

Stimulation and Lay House

- Stimulate hens based on achieving the target body weight. The Hy-Line Brown should be stimulated no lighter than 1350 g and no earlier than 15 weeks of age. Delaying light stimulation until 1500 g may help increase average egg weights. Use a 1 or 2-hour initial stimulation. The goal is to reach 15 to 16 hours of total light by 24 weeks of age.

- Adapt light intensity to the behavior of the hens, although interior light intensity may be controlled by local legislation. The recommendations are 20–30 lux at the level of the feed troughs or litter floor in aviaries. Hens might be exposed to much greater levels with windows, curtains, or free-range access. Lower light intensity inside the shed will help calm birds if necessary.

- Ensure that direct light does not shine into the nest box area and it is safe for birds to lay eggs without intrusion by other birds. Injurious pecking of the vent can occur in the nest when the vent is temporarily protruded after laying an egg.

Ventilation

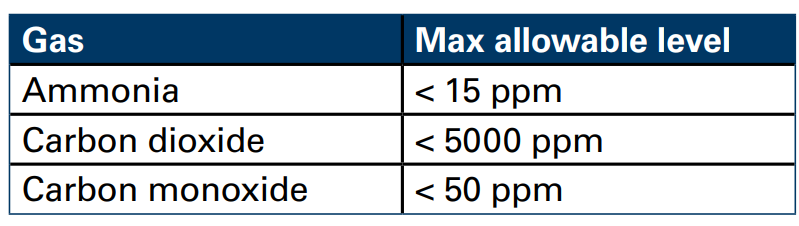

A poorly ventilated environment increases stress and leads to feather pecking behavior. When ammonia levels in a laying house exceed 15 ppm, the incidence of feather pecking increases by 10%. Similarly, as CO2 levels increase by 100 ppm, the incidence of feather pecking increases by 15%.

The ventilation system should be effective in removing CO2, ammonia, moisture, dust, and excess heat from the house environment. As every house ventilates differently, it is strongly recommended to consult a specialist to ensure that the ventilation system is operating optimally.

Negative air pressure ventilation systems are managed so that air is drawn from side inlets to the roof, where incoming air mixes with warm air and then circulates down through the house. This provides a homogeneous air temperature within the house and avoids cold air dropping from the air inlets directly onto the litter area, creating damp areas.

Positive pressure houses push exhaust air through vents and popholes, preventing cold, damp air in winter from entering the house and causing wet litter.

Natural ventilation systems (Figure 5) rely on thermal buoyancy. Birds generate warm air, which rises and is released through a ridge vent. As warm air exits, fresh air from outside the building enters the house via side inlets. Natural ventilation is influenced by outside weather conditions and more challenging to manage than mechanically ventilated systems. Natural ventilation, however, is generally not recommended where outside temperatures exceed 33°C.

Ventilation Recommendations:

- Heat the house before birds arrive from the rearing farm; the laying house must be warm as birds arrive.

- Ensure the environment within the laying house is optimal: 18–25°C and 40–60% humidity.

- Avoid gases exceeding maximum allowable levels (Table 1).

- Provide sufficient air circulation through use of supplementary fans during hot weather to aid cooling of birds.

- For further information on ventilation, refer to the Ventilation technical update.

Environment

A diverse, well-maintained hen environment reduces bird stress and has a beneficial impact on hens' behaviors.

Environmental Considerations:

- Consumable enrichments: Non-soluble stones/grit, pecking blocks, straw, alfalfa (Figure 6). Enrichments which are edible or contain edible components, for instance forage-based material, are more likely to be effective than non-edible material. Foraging behavior can be encouraged through addition of small quantities of grain or grit to the litter.

- Non-consumable enrichments: Hang ropes, egg flats, or CDs around the house.

- Structural enrichments: Verandas, winter gardens, elevated platforms, perches, and free-range paddocks are examples of structural enrichments to help keep hens stimulated. Higher usage of the freerange area is associated with less stress. Providing a shaded area (Figure 7) will encourage birds to range and provides shelter from the elements. Use of perches within the house environment can help avoid development of antisocial behavior by providing a safe area for less dominant birds.

- Recommended stocking density: Consider reducing bird group size by introducing partitions. Maintain consistency in stocking density across the environment by ensuring consistency in range access, temperature, ventilation, enrichments, food and water availability, or other resources.

Disease Management

Stress of any kind may lead to higher levels of adverse behavior. One source of stress for poultry flocks is chronic disease or pathogen loads. Reducing disease levels through biosecurity, vaccination, and proactive management will greatly aid the productivity of a flock. Consult your local veterinarian for a regionally appropriate vaccination and parasite prevention program. For additional information, refer to the Hy-Line Brown Alternative Management Guide and the Hy-Line Technical Updates on specific diseases.

- Viral diseases: Chronic viral challenges such as infectious bronchitis, avian metapneumovirus, lentogenic Newcastle disease can impact flocks without causing high mortality. These underlying viruses, especially in combination with Mycoplasma or E. coli can create hen discomfort and lead to stress.

- Bacterial diseases: Although often secondary, Mycoplasma and E. coli can also be primary pathogens that increase bird discomfort. Other bacteria such as Enterococcus, Staphylococcus, Campylobacter, and Clostridium are present at higher levels in aviary and freerange environments and if not properly managed can lead to management challenges.

- Parasites: The presence of red mite can lead to higher levels of stress which in turn increases the risk of feather pecking. Ensure there is an effective red mite prevention program in place for the lifetime of the flock. Intestinal parasites can be problematic on litter and free range systems.

Feeding System Management

A well-managed feeding system will not only support good performance but also promote good bird behavior.

- Access

- Maintain constant access to feed throughout the day from transfer to 22 weeks of age.

- From 22 weeks of age onwards, allow the birds to consume all the feed from the feeding system during the morning period. This will encourage consumption of small particles of feed. Ensure feed is adequately distributed around the entire feeding system quickly to avoid separation of components. A track speed of 20 m/ minute will distribute feed efficiently. Checking distribution of feed from the beginning to the end of the system is important, especially for longer systems over 120–130 m. Loading hoppers positioned halfway along the feeding system aids distribution of feed.

- Stimulate feed consumption by running the system without adding additional feed.

- Check the presentation of feed within the system, ensuring adequate depth, while at the same time preventing spillage.

- Set the feed system at an appropriate height (level with bird’s back) to allow birds to consume freely.

- Provide adequate drinker and feeder space to prevent competition and stress.

- Feed: 5 cm/bird (with access on both sides), 10 cm/bird (with access on one side), 4 cm/bird with circular feeders.

- Water: Nipples/cups: 1 per 10 birds; circular drinkers: 1 cm/bird; linear drinker: 2.5 cm/bird.

Nutrition and diet nutrient specifications

Diets fed to fully beaked flocks should not only provide the nutrients required to achieve optimum production, but should also support favorable behavior within the flock. Full nutrient recommendations are available in all Hy-Line Management Guides. Some key points pertinent to feeding fully beaked flocks include: achieving fiber levels, optimizing feed form, maintaining the consistency of nutrient supply, and fulfilling the nutrient needs of the bird.

Fiber

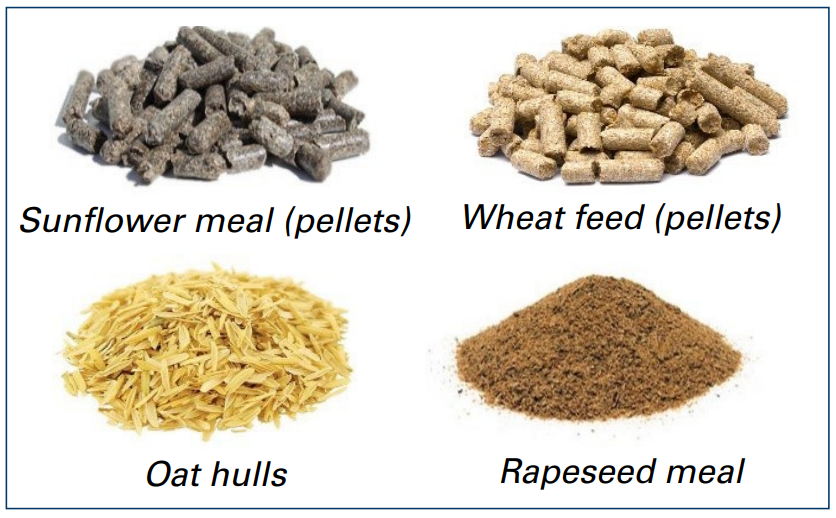

Increased insoluble fiber levels in layer diets have been shown to increase feeding time, which has a positive impact on bird behavior. Fiber also has a positive effect on satiety, gut function, and condition by stimulating gizzard activity and mechanical function3,4,5. Typical fiber levels are 3.5–4.5%; however, higher levels can increase feeding time and reduction in boredom and are associated with decreased feather pecking. Elevated fiber levels are attainable by adding more high-fiber materials such as sunflower, wheat feed, whole oat (hulls), or rape meal (Figure 8). Cellulosic products can also be used to increase the fiber level of the diet (based on supplier recommendations). Using a blend of fibers from a variety of sources is advisable.

Feed Particle Size

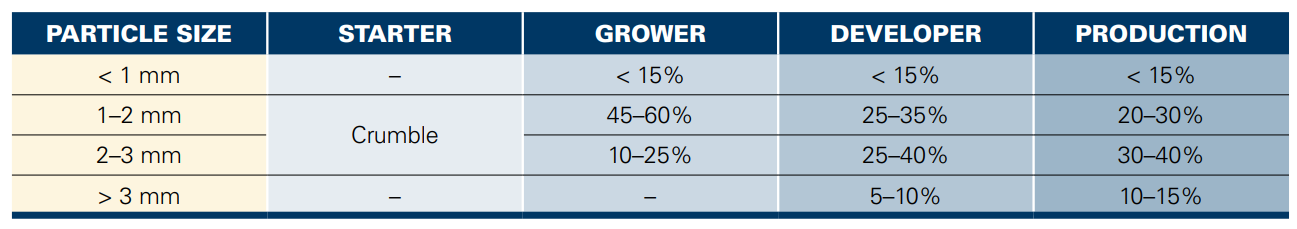

Feed particle size is nutritionally important and also engages hens in good feeding behavior. Utilize the Hy-Line feed particle size profile (Table 2) and aim for the majority of particles to fall between 1 and 3 mm. Particles above 3 mm should be kept within a maximum of 15% and not exceed 4 mm. The correct feed particle size will provide enough large particle size mash to stimulate a mechanical function to the intestine and enough small particles to engage the hens in longer feeding time.

- If the feed is too coarse, an excessive quantity of large particles may result in feed selection by dominant birds. This may lead to aggressive competition and uneven nutrient intake.

- If the feed is too fine, the ration will be less palatable, resulting in hens more likely to engage in explorative or boredom pecking.

- Adding fats and/or oils provides energy and increases the homogeneity and palatability of mash feed.

- Feeding mash is preferred, due to the longer feeding times relative to feeding pellets.

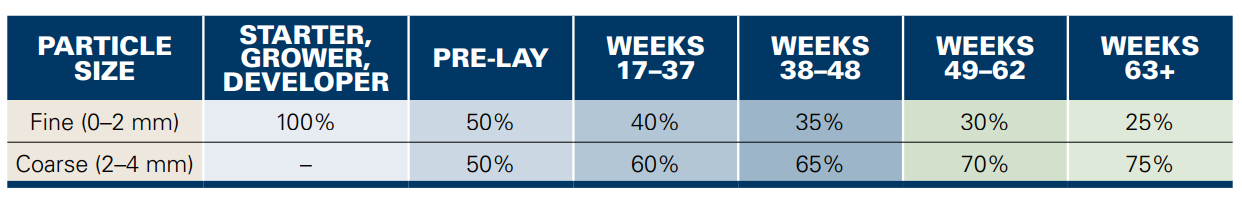

- Use large-particle limestone (2–4 mm) in layer diets. Larger particles not only support eggshell quality, but also provide a mechanical stimulus, which increases docility. The remainder of the limestone should be provided in smaller particles of 0–2 mm (Table 3).

Ensure large particles of limestone are adequately distributed through the feed. Uneven distribution will result in uneven presentation and potentially variable intake by birds. Mix feed components adequately during the manufacturing process.

Consistency of Nutrient Supply

- Base the nutrient density of the diet on the bird’s nutrient requirements (egg mass output) and feed intake. Birds eat quantities of nutrients (not percentages), so accurate estimation of feed intake when setting the diet nutrient specification is critical. A deficit in nutrient intake at any stage in lay may result in a stress reaction. This is particularly important in hot weather situations, where provision of key nutrients is critical.

- Ensure a consistent supply of key nutrients to the bird through lay. Transitioning to lowerdensity feed should be based on existing feed intake and egg mass output, rather than age.

- Minimize significant reduction in nutrient intake when transitioning through the feeding program. Introduction to the next stage diet should be managed to avoid triggering a behavioral response. Daily nutrient intake should not vary by more than 5%.

- Ensure an optimal amino acid intake and balance throughout both the rearing and laying period. Any shortfall or misbalance in amino acid intake may predispose birds to aggressive behavior. The main amino acids to consider are methionine, tryptophan, and arginine.

- Birds respond well to consistent diets with minimal compositional change. Maintain the same raw material use between diets and ensure inclusion levels do not change more than 20% between diets.

- Low or variable intake of micronutrients can impact bird behavior. Deficiency of pyridoxin and biotin is associated with feather pecking. Ensure birds consume fine particles of feed, which tend to contain micronutrients. Check that the vitamin and trace mineral specification of the diets is adequate.

- Sodium deficiencies often lead to pecking issues. If adverse behaviors are observed, check sodium and sodium chloride levels in feed samples sourced from the feeding system.

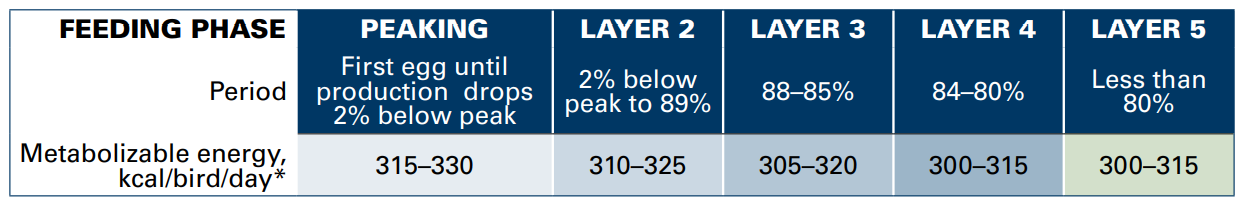

Energy Requirements

- Provide sufficient energy to support egg mass output (Table 4) and maintain ideal body condition. Hens with inadequate levels of body fat and muscle tone are more prone to developing behavioral issues.

- Check the condition of birds: at a minimum it should be possible to feel a 2 cm layer of skin/ subcutaneous fat around the abdominal area.

- Maintain adequate muscle condition. A breast muscle score of 3 is required after reachingmature body weights at 33–34 weeks of age (see Hy-Line Brown management guide).

*An approximation of the effect of temperature on energy needs is that for each 0.5°C change higher

or lower than 22ºC, subtract or add 2 kcals/bird/day, respectively.

| References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hy-Line internal data. | ||||

| 2. C Morrissey, KLH., Brocklehurst, S., Baker, L., Widowski, TM., Sandilands, V. | ||||

| (2016) | Can non-beak treated hens be kept in commercial furnished cages? Exploring the effects of strain and extra environmental enrichment on behavior, feather cover and mortality. Animals | |||

| 3. Krimpen, M. M. van, Kwakkel, R. P., Reuvekamp, B. F. J., Peet-Schwering, C. M. C. van der, Hartog, L. A. der and Verstegen, M. W. A. | ||||

| (2005) | Reduction of feather pecking behavior in laying hens by feeding management – a review.. Animal Science Papers and Reports, | 23(Suppl. 1), pp. 161–74. | ||

| 4. Lambton, S. L., Knowles, T. G., Yorke, C. and Nicol, C. J. | ||||

| (2015) | The risk factors affecting the development of vent pecking and cannibalism in free-range and organic laying hens. Animal Welfare | 24, pp. 101–11. | ||

| 5. Van Krimpen, M. M., Kwakkel, R. P., Van der Peet-Schwering, C. M. C., Den Hartog, L. A. and Verstegen, M. W. A. | ||||

| (2009) | Effects of nutrient dilution and nonstarch polysaccharide concentration in rearing and laying diets on eating behavior and feather damage of rearing and laying hens.. Poultry Science, | 88(4), pp. 759–73. |