Managing Incubation Temperature

There is a critical relationship between embryonic temperature, hatchability and chick quality, explains Marleen Boerjan of Pas Reform.As a breeder flock ages, the number of 'clear' (infertile) eggs increases as a result of decreased fertility and increased early mortality. Consequently, with higher numbers of clear eggs, a higher proportion of the heat produced by developing embryos in the fertile eggs is absorbed by the 'cold' clear eggs placed around them.

Embryonic temperature in the fertile eggs is reduced by a combination of the air flowing over them, together with the 'redundant' loss of heat absorbed by the clear eggs. To achieve optimum embryonic temperature in this scenario, we can compensate for the heat 'lost' to cold, clear eggs by increasing the temperature of the warm air flowing over the eggs.

|

The temperature of the air flowing over the eggs is governed by the incubator's temperature set-point. If air temperature is either too high or too low, the incubator controller adjusts cooling or heating rates respectively, until temperature set-point is reached.

When there are more than an average number of clear cold eggs positioned between developing fertile eggs, incubation temperature should be raised accordingly – in line with rates of fertility and early mortality in each particular batch of eggs. Estimates for these rates per different flock ages should be available in the hatchery's reference data, or in the breeder's management manual.

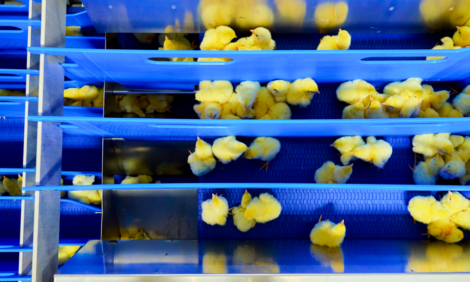

The hatchery manager knows that there is a critical relationship between embryonic temperature, hatchability and chick quality. Incubation temperatures that are set too low will result in increased mortality and a higher number of hatched chicks with a full belly.

Advice

- Routinely record, per batch of eggs, the percentage of clears, the hatchability of eggs set and hatchability in transferred eggs.

- Estimate the expected percentage of clears per batch of eggs. Adjust set points accordingly if this is less than 75 per cent (more than 37 clear eggs/tray).

- Identify the natural patterns of egg shell temperatures throughout incubation. During the first 12 days, optimum shell temperature is 37.8±0.1°C (100±0.2°F), followed thereafter by a gradual increase to 38.4 to 38.6±0.2°C (101.1 to 101.5±0.4°F) on day of transfer.

- Define optimum incubation temperatures by measuring the egg shell temperatures of a representative sample of eggs, randomly chosen from different trays in the incubator.

- Analyse random egg samples and use chick quality as a reference, especially if egg shell temperatures cannot be measured regularly.

- Consider increasing incubation temperatures if the air cell of dead-in-shell chicks is too small but first, ensure that this is not caused by relative humidity being too high in the incubator.

- Increase incubation temperatures if day-old chick quality indicates too low an incubation temperature. This applies if fewer than 50 per cent of chicks have a fully closed normal navel and 20 per cent have a thick belly (large yolk sac), upon detailed analysis of chick quality (Pasgar©score).

- Perform a detailed analysis of chick quality (Pasgar©score), to avoid reaching accidental conclusions when incubation temperatures are too low.

January 2012