MiteControl: how an integrated pest management approach can help control red mite

The poultry red mite (PRM) is the most damaging ectoparasite of laying hens worldwide. In Europe, where the infestation rate is over 80 percent the economic cost is estimated to be around €231 million per year.Part of Series:

< Previous Article in Series Next Article in Series >

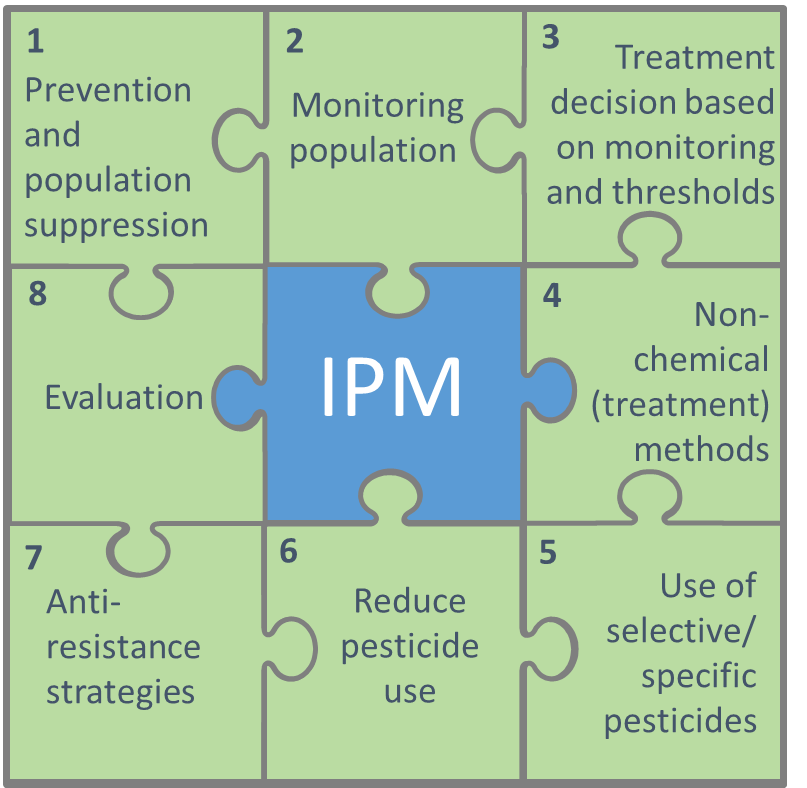

The MiteControl project aims to develop and test an integrated pest management (IPM) approach for controlling PRM on commercial pilot farms across the UK, France and Belgium. IPM is a widely used sustainable method for controlling pest species in horticulture and offers a potential long-term solution for the effective and sustainable control of PRM. IPM is generally based on eight steps (Figure 1), which enable the prevention and control of pest species while using chemical pesticides only as last resort. A practical starting point for implementing the IPM steps on laying hen farms is outlined below.

The eight different steps of integrated pest management © I Vänninen LUKE, Finland

1. Prevention and suppression

The first step is to prevent the introduction and dispersal of PRM throughout the laying hen facilities. The main preventative actions include:

- Staff and visitors – mites are primarily dispersed via people. Strict biosecurity measures, such as limiting the number of people who enter each house, changing clothes and boots in-between entering houses and hygiene barriers, all reduce the risk of mite transfer.

- Pullets – mites can easily be introduced through the delivery of pullets. Pullet rearers should monitor and control PRM in their facilities. Crates should be cleaned and disinfected before pullets are loaded. Turning lights on before catching should cause the mites to retreat to their hiding places, reducing the risk that they are on the pullets when caught.

- Egg trays – which are delivered to the farm need to be clean and mite free.

- Manure belts – which connect multiple houses can be highways for transfer. Where possible manure belts should serve just a single house.

Once PRM has been introduced into a house it is nearly impossible to eradicate. Suppressive measures must be implemented to keep mite numbers under control. Thorough cleaning between production cycles is very important – it is essential to remove all manure residues as these are potential hiding places for mites. During lay daily removal of manure has been found to reduce mite population growth by up to 79 percent.

2. Monitoring

An essential part of any IPM strategy is effective monitoring of the pest species. Several monitoring techniques have been developed to monitor PRM numbers:

- Visual – the Mite Monitoring Score (MMS) method requires mite levels to be visually assessed and scored at different points in the house. Although cheap and easy, it’s not very sensitive and is time consuming.

- Manual traps – traps provide a more reliable method of monitoring mite populations than visual techniques. Manual methods include: corrugated-cardboard tube traps, water traps, the AviVet trap and Velcro traps. Most of these methods require the trapped mites to be counted or weighed manually.

- Automated traps – are less labour intensive for routine sampling on farms. The “automated mite counter”, which has recently been developed, counts mites that enter the trap.

When using traps it is important that they are distributed throughout the whole laying house in locations that are frequently used by mites, such as beneath perches. It is recommended that at least 12 traps are placed in each house, and that they are regularly checked (at least once a fortnight).

3. Decision based on monitoring and thresholds

To avoid the unnecessary use of chemical treatments, and to prevent mite populations from getting out of hand, treatments must be used at the optimum time. To achieve this, pest-species thresholds need to be defined; ie identifying the level the pest population should reach before treatment should be deployed. Unfortunately no generally applicable thresholds are available for PRM control. The MiteControl project is aiming to address this.

4. Non-chemical treatments

Under an IPM approach, non-chemical strategies should be used first, before resorting to chemical treatments. There are a number of non-chemical treatments available for poultry farmers; these include: plant-derived products (eg essential oils), biological-control methods (eg predatory mites) and physical-control mechanisms, such as heat treatment of the poultry house, silica and diatomaceous earth and electrically adapted perches (eg Q-Perch). A more detailed description of non-chemical treatments can be found in this article. These methods can be used both preventively (step 1) or curatively after the mite population has exceeded a threshold (step 4). To increase the efficacy of non-chemical methods the MiteControl project is beginning to examine the benefit of combining several treatments.

5. Use of selective synthetic pesticides

Only where prevention and non-chemical treatments are insufficient should synthetic pesticides be used. Selective pesticides (those which just affect the target pest and minimise damage to the environment) should be used first. Unfortunately no chemical synthetic agent exists for the control of PRM that does not also have a toxic effect on other insects. With this in mind, acaricides which are least damaging to the environment should be selected and the overall amount of chemical product which is applied should be reduced.

6. Reduction of pesticide use

By only using chemical pesticides as a last resort, pesticide use should be reduced. It is also important to look at how the pesticide is used. Most chemical acaricides are applied as a spray or dust. One of the main disadvantages of spraying against PRM, is that mites hide in cracks and crevices during a large part of the day and these cannot be reached with a spray. The fluralaner-based product Exzolt is useful in this regard as it is administered through the drinking water, which is a more targeted method of distribution, which reduces adverse environmental effects.

7. Anti-resistance strategies

Mites have developed resistance against previously used acaricides such as carbamates and pyrethroids. This step requires products to be used carefully to avoid the emergence of resistance. This can be achieved by reducing pesticide use (step 6), by using products at the correct dosages and by combining and/or rotating different products. It is important that combined or rotated treatments have a different mode of action in order to avoid resistance emergence. Understanding which treatments are compatible is one of the key aims of the MiteControl project.

8. Evaluation

The effectiveness of the IPM approaches should be continuously monitored and evaluated. Given the large number of influencing factors in commercial poultry houses, one IPM strategy might not have the same efficacy on every farm. It therefore important that the IPM strategy is evaluated and tailored to meet the specific needs of the farm.

The MiteControl project is part funded by the European Regional Development Fund provided by the Interreg North-West Europe Programme. In the UK it is generously supported by BFREPA, the BEMB Research and Education Trust and Noble Foods.