Poultry Heroes: John Brunnquell tells all about setting hens free

Free-range egg producer John Brunnquell puts poultry health and wellbeing at the heart of everything he does.When third-generation egg farmer John Brunnquell was 22-years old he could espouse all the benefits of caged production. “Birds don’t walk around in their own manure,” he said, “and if they get sick they can be fed quickly.”

“Cages protect them from predators,” he added. But one day when he walked into a cage-free barn, what he saw made him question everything he thought he knew for certain. It was, as he put it, “the beginning of the journey.”

As a young lad, Brunnquell (now 56) grew up on a small family farm with 7,000 chickens. Like other rural American kids his age, Brunnquell joined 4-H. Later, he pursued a Bachelor of Science in Agronomy and a Masters in Poultry Science, both from the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Today, Brunnquell is president and founder of Egg Innovations, a unique model for organic, free-range egg production, and he is pursuing a PhD in Avian Ethology at the University of Kentucky. “At my heart, I’m a behaviourist,” he said. “I ask the question ‘why’ all the time.”

Understanding hen behaviour

The transition from a young man who knew why caged production was the only choice, to a leader in organic production in the US prompts many important questions. Why, for instance, do we open the doors to allow birds to go outside when only some will use the opportunity? Why, when they go outside, do they go to certain areas? Why do the exact same genetics perform differently under different production systems? What’s the best way to get birds inside at night without hurting or scaring them?

“I asked these types of questions all the time,” said Brunnquell, who believes that every animal on Earth is hardwired to perform certain behaviours. He said that, if given the opportunity, animals will express those hardwired behaviours.

“In the case of a chicken, it is hardwired to perch, to scratch, to dust bathe, to pasture and to socialize,” he said. “If you give it an environment where it’s allowed to do that it will display those behaviours in high percentages.”

As the founder and president of Egg Innovations, Brunnquell has designed a building that specifically focuses on the behaviour of animals. Egg Innovations owns 65 layer barns that house 20,000 birds in each barn. It’s a contract model where the farmer owns the building and pays for labour and utilities. Brunnquell owns the birds and farmers are paid at the upper end of the market. All of the 1.5 million birds under this model have access to the outdoors each day. Of the 65 barns, 60 percent are located in Indiana; the remaining farms are located in Wisconsin and Kentucky.

“My barns all have very dedicated perch areas, dedicated scratch areas, dedicated pasture areas - and we leaned into their behaviour,” he said. “If this is the way the animal wants to behave, why don’t we design a building that lets them behave that way? In theory, good things should happen. And that’s what we found.”

By “good things” Brunnquell isn’t just talking about improved animal welfare, but also improved production. When genetics companies put out their breeder guides, they include information on the production value of the breed at different ages. Brunnquell said his birds consistently outperform those numbers.

“They have a column that says under optimal conditions, it will perform at this level,” he said. “We use that as a benchmark; on average, we produce at 102 percent of optimal standards.”

Improvement, however, didn’t come immediately. It came gradually with each change. There was obvious improvement in flock performance, for instance, when he transitioned from caged to cage-free production. “Then we put perches in and let birds outside,” he said. “Every time we took an incremental step, we saw improvements in production and drops in morbidity and mortality.”

Sometime after making the transition, Brunnquell decided to pursue a PhD to better understand hen behaviour. He has since learned about bi-modality (understanding why some birds go outside when others don’t) and allostasis (achieving stability and balance through physiological or behavioural change). He applies this knowledge to Egg Innovations. He hopes that what he does will not only influence the way Americans eat eggs, but also how farmers produce them.

“I don’t know if I’ll achieve those goals, but along the way I expect we’ll have a little bit of influence,” he said.

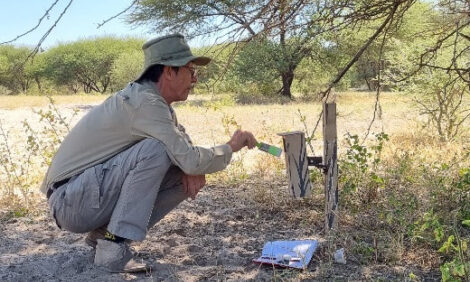

What is especially unique about Egg Innovations is that all 65 buildings are identical - the same length, the same width and housed with the same equipment. Having 65 perfectly replicated barns for commercial-sized flocks is the perfect tool for conducting research. Brunnquell works closely with researchers from the Center for Proper Housing, Poultry and Rabbits (ZTHZ) in Switzerland. Led by Michael Toscano, ZTHZ researchers run small-scale trials with the goal of better understanding hen behaviour. Sometimes Brunnquell applies their research in his barns to see if what they’ve found works on the commercial scale. The relationship benefits both parties.

In one of his projects, Brunnquell examines how light, particularly light wavelength, impacts hen behaviour during depopulation. The literature seems to support the idea that blue LED lighting calms the birds, which leads to more injury-free depopulation.

Brunnquell is unique in the US poultry industry, and sometimes takes flack for deviating from the norm. Undeterred, his long-term goal is to examine and improve poultry welfare from cradle to grave. It’s this kind of curiosity - and dedication - that makes John Brunnquell a poultry hero.