Role of Dietary Fibre and Litter Type on Development of Necrotic Enteritis in Broiler Chickens Challenged with <em>Clostridium perfringens</em>

No protection from necrotic enteritis was provided by a high–fibre diet and/or hardwood litter consumption when broilers were challenged with C. perfringens, S.B Wu of the University of New England reported to the Australian Poultry Science Symposium 2011.Summary

Increased structural fibre in the diet and/or ingestion of hardwood litter have shown similar

effects to coarse feedstuffs or feedstuffs containing coarse components such as whole grains,

which can stimulate gizzard development. It is not clear whether increased dietary fibre

and/or ingestion of hardwood litter can provide birds with a degree of protection when

exposed to a Clostridium perfringens strain known to induce necrotic enteritis (NE).

In the

present study, it was shown that dietary fibre and litter type had no effects on relative gizzard

weight of birds measured at day 14 days of age. On the other hand, there were indications of

an interaction between diet and litter type on gizzard weight at day 17. In birds raised on

paper, those given a low–fibre diet had smaller gizzards than those given a high fibre diet,

whereas birds raised on hardwood were unaffected by dietary fibre.

Meanwhile, dietary fibre

and/or litter type altered the intestinal pH, short chain fatty acids (SCFA), and some microbial

groups, but not the whole microbial community.

It was concluded that, despite a degree of

response to the treatments, no protection of birds from NE by high fibre diet and/or hardwood

litter consumption was detected when the birds were subjected to C. perfringens infection.

Introduction

Ingestion of even small quantities of litter with large and/or hard particles stimulates gizzard

development. These findings are consistent with published studies showing increased gizzard

weight and improved gizzard function in broilers given either a coarse feed or feed containing

coarse components, such as whole grains (Engberg et al., 2004; Svihus et al., 2004).

Another

important benefit arising from enhanced gizzard development is the potentially positive role

of a functional gizzard in control of bacterial populations. Whole wheat feeding has been

reported to significantly reduce the numbers of C. perfringens in the intestinal tract of birds

(Bjerrum et al., 2005). This indicates that a functional gizzard may act as a barrier organ

preventing potential pathogenic bacteria from entering the distal digestive tract. Thus, if

access to gizzard stimulating litter materials has a significant impact in broiler chickens,

choosing the right litter material may have important health implications in relation to

reduced occurrence of NE, which is strongly associated with C. perfringens.

Alternatively,

increased structural fibre in feed may have health benefits in terms of reduced enteric

bacterial infections.

This study aimed to determine whether enhanced gizzard development

achieved by either increased dietary fibre concentration or by ingestion of hardwood litter,

had a beneficial impact on health and productivity of birds challenged with C. perfringens.

Materials and Methods

One thousand, two hundred day-old Cobb male broiler chickens (42.4±0.1g; from Baiada

hatchery, Kootingal, NSW, Australia) were raised in 48 floor pens. Each pen was assigned to

one of eight treatment groups with variables of paper versus hardwood litters, high fibre versus control diets, challenged versus unchallenged by C. perfringens with six replicates per treatment. The

pelleted high fibre diet contained 7% of soy hull. The birds were fed starter diets during days

1 to 7, 30 per cent fishmeal was added to the starter diet to induce stress on birds’ gastrointestinal

tracts during days 8 to 14, and fed finisher diets from days 22 to 28.

The procedure for

challenge of birds in corresponding groups was as described by Wu et al. (2010). On days 14,

15, and 16, birds to be challenged were inoculated per os with 1ml of C. perfringens (type A

strain EHE-NE18, CSIRO Livestock Industries, Geelong, Australia) suspension at a

concentration of 108–109 colony-forming units (CFU) per ml. The strain, EHE-NE18, produces a novel toxin NetB,

which plays a major role in the pathogenesis of NE in the chickens (Keyburn et al., 2008).

Birds in the unchallenged group received 1ml of sterile thioglycollate broth.

Feed

consumption and live weight of the birds were measured on days 8, 15, 22 and 28 of the

experiment. Live and adjusted body weight, body weight gain and feed conversion ratio

(FCR) were calculated. FCR within a period was adjusted for mortality.

On days 14 and 17,

two birds were randomly chosen in each pen and sacrificed for sample collections. Total

body weight of each bird was recorded, and the proventriculus, gizzard, small intestine,

pancreas, liver, spleen and bursa were removed and weighed individually. The contents of the

gizzard, ileum and caeca were pooled for the birds sacrificed in each replicate. pH of the

contents was measured, and approximately 1g of the digesta was collected for microbial

culture, and the remaining digesta stored for determination of volatile fatty acid analysis. An

approximately 3–cm section of ileum (including digesta) mid-point between the Meckel’s

diverticulum and caecal tonsils, and one caecal lobe (including contents) per bird were

sampled for DNA profiling.

Analysis of SCFA, enumeration of individual intestinal bacteria

and profiling of total microbial community using T-RFLP analysis were performed.

All data except those of T-RFLP were analysed using the statistical package SAS for Windows

version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Significant differences between means were

detected by pair-wise t-tests, or data were analysed by the non-parametric one-way analysis

of variance procedure when the data were not normally distributed. The T-RFLP data were

analysed as described previously (Torok et al., 2008).

Results

High dietary fibre provided by soy hulls had no effects on adjusted liveweight except for

birds being significantly heavier at day 8. Similarly, there was a significant improvement in

adjusted FCR in the period 0-8 days of age for birds given soy hulls. However, increased

dietary fibre level was disadvantageous for FCR during the periods of 0-15 and 0-22 days of

age.

Litter type had no effects except for increased liveweight on hardwood litter at 28 days

of age. Challenge with C. perfringens had deleterious effects on live weight at 15 and 28 days

of age, with significantly poorer FCR in the periods 0-15, 0-22 and 0-28 days of age.

The

challenge also resulted in highly significant losses of birds in the periods 15-17 days.

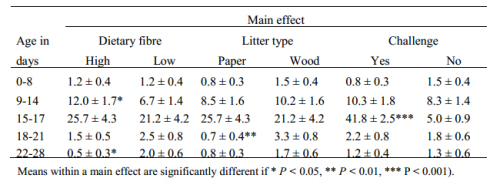

Addition of soy hulls to the diet, and hardwood litter resulted in a significant increase of

mortality in the periods 9-14 days and 18-21 days of age, respectively, but soy hulls in diets

significantly eased mortality rate during the last week of the trial (Table 1).

Dietary fibre and litter type had no effects on any of the organ weights except for an

increase in weight of the bursa which approached significance (P=0.052). Challenge with C.

perfringens resulted in a highly significant increase in weight of the small intestine and a

significant decrease in liver weight. Dietary fibre and litter type had no effects on relative

weights of proventriculus, small intestine, liver, spleen and bursa, and challenge with C.

perfringens resulted in significant increases in weights of the proventriculus, small intestine

and bursa.

The relative weight of the gizzard was significantly affected by interactions

between diet and litter type, diet and challenge, and litter type and challenge. Reduction in gizzard size was significant (P<0.05) in birds housed on paper litter and given a low–fibre

diet. Birds given the high–fibre diet showed a greater decline in gizzard weight when

challenged, compared with birds on a low–fibre diet.

Birds housed on wood litter showed no

decline in gizzard size when challenged, whereas birds on paper showed a significant decline

in gizzard weight. The three-way interaction was not significant (P>0.05). The relative weight

of the pancreas was affected by interaction between litter type and challenge. Birds housed on

paper litter showed a significant decline in pancreas weight when challenged, whereas

pancreas weight was unaffected by challenge when birds were housed on wood litter.

|

| Table 1. Main effects of dietary fibre, litter type and challenge with C. perfringens on mortality (means ± SE) |

High dietary fibre significantly increased acetic, propionic, isobutyric and butyric acids

in caecal contents and depressed formic acid compared with low dietary fibre. There was a

tendency for high fibre to increase lactic and succinic acids in ileal contents.

Paper litter

depressed the concentration of succinic acid in caecal contents and tended to increase acetic

acid in caecal contents. The challenge procedure significantly increased lactic and succinic

acids in ileal contents, and depressed concentrations of formic and acetic acids in caecal

contents. There were tendencies for challenge with C. perfringens to raise concentrations of

isobutyric acid and lactic acid in caecal contents.

Dietary fibre and litter type had no effects on pH in gizzard, small intestine and caeca

at day 14. The challenge procedure significantly raised pH in the small intestine and caeca at

day 14. On day 17, high dietary fibre significantly increased pH of the gizzard whereas

challenge with C. perfringens lowered pH of the caeca.

On day 14, birds on hardwood litter had significantly higher counts of the total

anaerobes, lactobacilli and lactic acid bacteria in the ileum, and a significantly lower number

of anaerobes in the caeca.

Challenge had no effects on numbers of different organisms in the

ileum, but significantly raised numbers of enterobacteria and coliform bacteria in the caeca

and depressed numbers of lactose-negative enterobacteria.

In contrast to day 14, at day 17

litter type had no effects on bacterial counts in the ileum or caeca, whereas challenge with C.

perfringens significantly increased numbers of lactic acid bacteria, C. perfringens, and

enterobacteria in the ileum, as well as C. perfringens, enterobacteria and lactose-negative

enterobacteria in the caecum.

Although there was a trend towards a difference (P=0.06)

between the NE–challenged and unchallenged control groups in the caecal microbial

communities of birds aged 17 days which had been raised on the high–fibre diet and paper

litter, no significant effects of the treatments were detected on the whole microbial

community.

Discussion

The hypothesis tested in this study was that enhanced gizzard development through increased

dietary fibre and/or ingestion of hardwood litter would provide birds with a degree of

protection when exposed to a strain of C. perfringens strain known to induce severe NE, with

accompanying high mortality, and depression of live weight and FCR.

The NE challenge procedure was highly successful in that birds exposed to C.

perfringens via oral gavage showed severe symptoms of NE, resulting in depressed liveweight gain, poorer FCR and raised mortality.

Anticipated protection from enhanced gizzard

development was not evident, possibly because dietary fibre and litter type had no effects on

relative gizzard weight of birds measured at day 14.

In this study, it was observed that an

interaction between litter type and challenge tended to produce a lower gizzard weight in

birds raised on paper litter and subsequently challenged, which is consistent with the

expectation that a bird with a poorly developed gizzard may be disadvantaged when faced

with an enteric bacterial challenge, compared with flock mates with larger gizzards.

The general lack of effects of dietary fibre and litter type on relative organ weights at

days 14 and 17, with the exception of an enlarged proventriculus in birds on paper litter, and

reduced gizzard weight in birds given low dietary fibre and raised on paper, is not consistent

with previous findings (Ali et al., 2009; Hetland et al., 2005; Hetland et al., 2003). The

underlying causes of these discrepancies warrant further investigation.

High dietary fibre

resulted in increased concentrations of some SCFA (acetic, propionic, isobutyric and butyric),

which have been associated with protection of birds from enteric infections due to their

bactericidal properties (Ricke, 2003). Nevertheless, these increases appeared not to protect

birds from C. perfringens infection; however, the infection was very severe in this study,

which may have compromised the possible effect of high dietary fibre. In less severe cases,

perhaps elevation of SCFA would offset performance and mortality losses.

The hypothesis that enhanced gizzard development through increased dietary fibre

and/or ingestion of hardwood litter provides birds with a degree of protection from NE

induced by C. perfringens was not supported by results obtained in this study.

Acknowledgement

The Australian Poultry CRC provided financial support (Project number 06-18).

References

Ali M., Iji P.A., MacAlpine R. and Mikkelsen L.L. 2009. Australian Poultry Science Symposium, 20:77-80.

Bjerrum L, Pedersen K., and Engberg R.M. 2005. Avian Diseases, 49:9-15.

Engberg R.M., Hedemann M.S., Steenfeldt S. and Jensen B.B. 2004. Poultry Science, 83:925-938.

Hetland H., Svihus B. and Choct M. 2005. Journal of Applied Poultry Research, 14:38-46.

Hetland H., Svihus S. and Krogdahl A. 2003. British Poultry Science, 44:275-282.

Keyburn A., Boyce J., Vaz P., Bannam T., Ford M., Parker D., Di Rubbo A., Rood J. and Moore R. 2008. PLoS Pathogens, 4:e26.

Ricke S. 2003. Poultry Science, 82:632-639.

Svihus B., Juvik E., Hetland H. and Krogdahl A. 2004. British Poultry Science, 45:55-60.

Torok V.A., Ophel-Keller K., Loo M. and Hughes R.J. 2008. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 74:783-791.

Wu S.B., Rodgers N. and Choct M. 2010. Avian Diseases, 54:1058-1065.

Reference

Wu S.B., L.L. Mikkelsen, V.A. Torok, P.A. Iji, S. Setia and R.J. Hughes. 2011. Role of dietary fibre and litter type on development of necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens challenged with Clostridium perfringens. Proceedings of the Australian Poultry Science Symposium. Sydney, Australia. February 2011.

Further Reading

| - | You can view the Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Australian Poultry Science Symposium by clicking here. |

Further Reading

|

| - | Find out more information on necrotic enteritis by clicking here. |

April 2012