US Poultry Industry Manual - Scope of the backyard poultry production

Learn more about raising poultry in your own backyardPart of Series:

< Previous Article in Series Next Article in Series >

Editor's Note: The following content is an excerpt from Poultry Industry Manual: The Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (FAD PReP)/National Animal Health Emergency Management System (NAHEMS) Guidelines which is designed to provide a framework for dealing with an animal health emergency in the United States. Additional content from the manual will be provided as an article series.

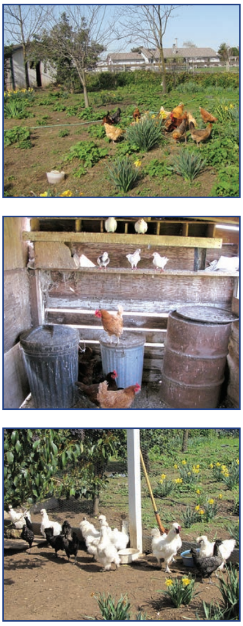

Backyard poultry production is as varied and inclusive as are the myriads of backyards that house the birds. If enough backyards are visited, every conceivable poultry housing type and husbandry method will be observed. Backyard poultry, kept for all possible purposes, as well as pet birds of all types are maintained in various numbers and combinations (commonly included with a wide variety of non-avian species) in all types of neighborhoods and areas ranging from the most urban to the most rural -- even in isolated apparently inhospitable areas such as the remote desert. In many areas, the presence of backyard poultry is hardly noticeable; in other areas chickens as well as other poultry species roam and/or fly about freely. Some backyard poultry owners operate highly elaborate systems for breeding and/or raising birds and keep detailed records of their genetics and production. Others leave the birds to more or less fend for themselves among the vast array of untended objects and clutter on an enormous variety of premises.

Great differences in backyard facilities and husbandry practices present a widely variable series of challenges to taskforce personnel responding to an event of a highly contagious avian disease, such as avian influenza or exotic Newcastle disease. Surveillance, diagnostic, depopulation, and cleaning and disinfection teams will encounter every imaginable set of circumstances and all types of conditions in which they will have to conduct their activities. Great variation also will be encountered among backyard poultry owners. Some are highly cooperative, informed, sophisticated producers while others are the extreme opposite and difficult people with whom to deal. Some are openly belligerent to government employees. This latter category, although rare, sometimes makes it necessary to obtain judicial warrants and assistance from law enforcement in order to depopulate poultry during an exotic disease control event.

As will be seen throughout this chapter, the universal theme is that backyard poultry are ubiquitous, commonly found in all imaginable types of backyard facilities, and are kept under all possible husbandry circumstances by a wide spectrum of owners for as many purposes and reasons as there are owners.

Demographics

Keeping poultry in backyards is a widespread and very popular hobby that is practiced throughout society in every conceivable manner and place, in all circumstances including the most urban of neighborhoods. Likewise, production and husbandry practices are as many and varied as the number of places that keep poultry. Backyard poultry most commonly refers to chickens, however, the word poultry is defined in statutes and regulations in various ways in different states and countries to include numerous species even domestic rabbits (1). Certain species may be included as poultry in some states, but not in others. The World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), formerly known as the Office International des Epizooties, defines poultry as, “all domesticated birds, including backyard poultry, used for the production of meat or eggs for consumption, for the production of other commercial products, for restocking supplies of game, or for breeding these categories of birds, as well as fighting cocks used for any purpose” (2).

The term, “backyard poultry,” however, has never been clearly defined. It would seem obvious that avian species defined as poultry and kept in a backyard would qualify as “backyard poultry.” However, the dividing line between backyard flocks and small commercial flocks remains unclear and arbitrary, and difficult to precisely define. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS) Poultry ’04 study (3) used the number of birds (other than, or in addition to pet birds) per residence as the dividing line between backyard (fewer than 1,000 birds) and commercial poultry operations (1,000 or more birds).

In the event of an exotic disease outbreak, such as avian influenza or exotic Newcastle disease, many if not all domestic and captive avian species may be targeted for disease control and eradication activities. These activities will bring responders, such as members of the National Animal Health Emergency Response Corp (NAHERC), into contact with a wide variety of backyard poultry facilities and circumstances. Pet birds continuously kept inside homes or in backyards may or may not be included in disease control protocols. In a disease control deployment, taskforce management will make these determinations and communicate that information to operations personnel. If there is any doubt about taskforce directives, responders should ask for complete clarification prior to taking any definitive action.

The USDA Poultry ‘04 study found an average of 29.4 residences that were located within a 1-mile radius of a commercial poultry operation. Of these, 1.9 had backyard poultry flocks (3,4). The primary reason cited for owning backyard birds was for pleasure or hobby (40.6%) while about 25% of owners cited food or family tradition (3,4). In backyard flocks, egg layer chickens were found in 63.2% of the premises and represented 37.5% of all birds. Pet birds made up only 0.3% of the total bird population of backyard flocks. The presence of guinea fowl varied from 4.3% in the East to 31.7% in the Midwest (3).

An average backyard flock consists of 35.1 birds (average numbers of birds per flock ranged from 26.1 in the Southeast to 49.2 in the East). Almost one third of backyard flocks consist of fewer than 10 birds (3). Backyard poultry owners may have only a single pet chicken or duck, maybe a few hens for egg production, perhaps a mixed group of exotic chickens for breeding and/or show purposes, possibly in conjunction with some ducks, geese, guineas, or countless other combinations. In other situations, backyards may contain substantial numbers of birds. Applicable zoning laws may preclude or limit the number of birds that can be kept. However, such restrictions and limitations are frequently ignored by owners and overlooked or poorly enforced by animal control agencies that consistently must operate with limited personnel and diminished budgets.

Gamefowl (fighting cocks) were reported in about 50% of backyard flocks in the southeastern U.S., but in only 4.1% of backyard flocks in the eastern region. In certain areas and ethnic neighborhoods, gamefowl are a consistent finding and may be present in highly variable numbers.

Pet birds are commonly kept and/or propagated in backyards. Small birds such as finches or quail, can be kept in extremely large numbers within a small space. As with most aspects of backyard poultry, there is great variability among pet birds regarding species, numbers, housing, purpose and use of the birds which are commonly found in urban, suburban, and rural neighborhoods. Owners belong to all ethnic and all age groups.

In certain areas, and particularly with gamefowl owners, it is common to find multiple owners that have rented small portions of a larger facility to house their poultry. Facilities originally designed and previously used as horse stables or stalls are frequently converted into chicken coops by urban and suburban gamefowl industry members. Concerns and considerations for disease spread and control are particularly high during the cockfighting season which begins on Thanksgiving Day and continues until the following August. Gamefowl may be transported and moved frequently and over long distances putting these birds at increased risk of contracting or spreading an exotic disease.

Hobby birds of many kinds are found in backyard as well. These birds may include racing pigeons, which technically are not poultry (unless they are raised for human consumption), but nevertheless are susceptible to many of the same diseases as poultry. Hobby birds, by their very nature, frequently travel and/or are transported over long distances at frequent intervals. Additionally, it is not uncommon to find ratites, such as ostriches and emus but rarely rheas, in backyards. As stated repeatedly, the only consistent component of keeping and rearing of backyard poultry (and other birds) is variability.

Business structure

The highly variable nature of backyard poultry production means that, for most owners, there is no business structure or there may be a loosely defined business. This is because, in many cases, poultry keeping is more of a hobby than a business. Many hobby flock owners do not keep records of any kind or they may keep minimal records which may amount to a desk drawer full of feed store receipts. In these situations, birds are maintained only for the enjoyment of the birds per se, or to produce a few eggs for home use. In some cases, small flocks are maintained for the purpose of selling a few eggs in the neighborhood, possibly because they may have the appeal of being the source of local free-range or organic fresh eggs.

There are a few exceptions to this type of recordkeeping. Bird fanciers raising show birds usually maintain elaborate records of their birds detailing the genetics, breeding and production of birds and/or hatching eggs. An occasional gamefowl producer/breeder may keep elaborate computerized records of the genetics and production of each member of the entire flock and work for years to develop their “ideal” fighting cock. The fighting cock industry, which may range from a weekend hobby to a substantial commercial enterprise will, therefore, vary greatly among owners regarding the business structure and types of records they maintain.

Components

In the event of an exotic disease outbreak, responders to backyard poultry issues may encounter a wide spectrum of poultry as well as many other avian and non-avian species kept in the backyard setting. Many times, a hodgepodge of many species of birds will be encountered in the same backyard and frequently along with various other non-avian species. This collective group of backyard poultry and other types of birds are kept for a variety of reasons and purposes, such for pets, a hobby, egg and/or meat production, 4H or FFA projects, or cock fighting. The OIE definition of poultry appears to include pigeons that are raised for meat or egg production, but does not include racing pigeons unless one construes the meaning of “other commercial product” (see Section 1.1) to include the commercial aspects of racing as a product.

Clubs: Numerous and varied poultry fancier clubs exist, members of which raise their birds in backyards. Multiple exotic breeds may be present in the same backyard. These birds frequently are exhibited at breed shows or various other poultry shows. University Avian Sciences Extension and/or Veterinary Extension faculty frequently interact closely with such fancier clubs and, therefore, are an excellent source of further information and liaison contact with members.

Project poultry: Project poultry are poultry that are kept and raised by students for 4-H or FFA projects. Project poultry may be raised for many purposes, including egg laying and meat production. If they are of a recognized or exotic breed, project birds may be exhibited at local fairs or state fairs in competition for awards and prizes or to satisfy the need for a school project. Because these birds are transported into congregation points and then go out again to other events, there is an element of risk for disease transmission and spread. Many fairs and poultry exhibitions have established inspection points for all birds entering the premises. Poultry Health Inspectors (PHI’s) are usually trained by or associated with university extension services and examine birds before they are admitted to an event (5). Any bird showing signs of contagious disease may be excluded from admission onto the premises and is referred to a veterinarian for further evaluation.

Gamefowl: A substantial component of backyard poultry is made up by the gamefowl (cockfighting) industry. This industry is only beginning to be understood, primarily as a result of the 2002-03 exotic Newcastle disease epidemic in California, Nevada, Arizona, and Texas. Individual holdings within the gamefowl industry are highly variable with flocks ranging from a few birds in a backyard to thousands in large elaborate commercial enterprises. Estimates of total numbers of gamefowl range from 3-8 million birds in California alone, held by some 50,000-60,000 owners. California’s gamefowl industry represents an estimated 33-40% of the total national gamefowl flock which may consist of some 8-24 million birds. Game fowl owners represent many racial and ethnic groups with the majority being Hispanic but also including Caucasian, Filipino, Vietnamese, Thai, Cuban, Hmong, and Chinese. Some are involved in the sport whereas others raise the birds simply because they are fanciers of the breeds. There are about 750 California members in the United Gamefowl Breeders Association, a national organization made up of about 15,000 gamefowl breeders and 150,000 gamefowl owners (5).

Doves and Pigeons: Doves and Pigeons: Although not considered poultry in United States federal regulations (7), or in California state regulations (9) unless they are to be used as human food, doves and pigeons are commonly found in backyard settings. Often these birds are kept purely for the pleasure of owning them or for production of squab meat. Fancy pigeons are frequently very expensive birds and may require a special appraisal if they have to be depopulated. Racing pigeons, or homing pigeons, are routinely transported long distances and then released to fly home. This activity presents some concerns about spreading disease, especially if an exotic disease outbreak or a quarantined area exists along their flight pathway. A policy for handling such species should be adopted and implemented by taskforce management in disease control activities.

Upland Game Birds: While upland game birds such as pheasants, quail, and chukars are usually raised in commercial facilities for sale to hunt clubs or to live bird markets, they also may be encountered in backyards where they may be raised for home consumption. These species, in addition to being raised for meat, are sometimes kept as purely ornamental birds, particularly the exotic types like Golden pheasants. Because of their very small size, quail may be raised in large numbers in very small spaces. It is entirely feasible that commercial quail production may be conducted in backyards or inside industrial buildings with no outward indication that any type of birds may be present. Raising game bird species may require a permit from the state’s wildlife or fish and game department. In California, the Department of Fish & Game has regulatory authority over breeding these species in captivity (8). This regulatory agency may be contacted to assist emergency disease responders locate game bird breeders in an outbreak event.

Pet Birds: Pet birds include such species as parakeets, cockatiels, parrots, finches, canaries, and mynah birds, but also may include almost any species including chickens, ducks, and sometimes turkeys that have been hand raised from babies at Easter time. The author has observed a group of adult pet turkeys that were allowed to live and roost inside their owner’s home.

Ratites: Ostriches and emus may be found in backyards, but rheas are less common. These species present their own unique challenges to taskforce personnel who may be assigned to disease surveillance testing, diagnostic teams, or to depopulation and disposal crews. Restraint and handling of these species can be difficult and dangerous, and is best left to the owner whenever possible. When taskforce personnel must handle these birds, chemical restraint in addition to the owner’s assistance is essential, particularly if the flock is to be depopulated. Owners may be given the option to depopulate their own birds if they wish to do so. This activity should be monitored to ensure that all appropriate birds are depopulated. If the depopulation and disposal team is to handle ratites, it is most beneficial to ask the owner or a veterinarian familiar with ratites for assistance in capturing and restraining the birds. Use of chemical restraint, i.e. sedative and/or anesthetic drugs, makes depopulation much easier and safer for the disease control team. Various drugs are readily available for this purpose, although many of them are scheduled controlled substances that will require a Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) license to purchase, possess and use. Inventory control records to account for these scheduled products are required to be kept.

Other Varieties: Backyards have been observed to contain virtually any and all kinds of other birds, including but not limited to: guinea fowl, peacocks, finches, mynah birds, parrots, love birds and many other species. Some of these birds may be kept in cages within the owner’s home. In advance of an outbreak situation, protocols should be developed regarding the policies and contingencies for handling in-house cage birds in the event of a highly contagious disease outbreak requiring disease control action.

Economics

Most backyard poultry and hobby birds are kept solely for the owner’s use and enjoyment and have little economic impact other than that resulting from purchases of feed, equipment and other supplies, or perhaps from sales of eggs or young birds that might be produced. However, gamefowl raised in backyards frequently do have significant financial importance to the owners. Income generated by gamefowl was estimated at $50 million annually in California in 2001 (5). Sales of gamefowl exported to other countries were estimated at about $125 million annually. In addition to sales of these birds, winnings from cockfighting events and “Derbies” are likewise substantial (5).

Allied industries

For the backyard poultry producer or hobbyist, the local feed store serves as the central hub or meeting point where not only feeds and supplies are obtained, but husbandry questions, health issues of the birds, and virtually any other subject pertaining to backyard poultry are discussed and advice sought and/or given. Also, feed stores serve as a common location where all the biosecurity issues of all the customers’ premises may come together.

Foot traffic from each premises commonly ends up in the feed store on a regular basis and has the potential to bring with it disease organisms that can then be transported to other premises on the shoes of other customers of the store. The situation is somewhat similar to large commercial feed mills that have trucks going onto commercial poultry premises with the potential of carrying disease organisms on the vehicles and/or the driver’s shoes and clothes. Because of this, there is a degree of risk of spreading diseases via the feed stores. Likewise, there is an opportunity for flock owners to practice good biosecurity between the backyard flock and the feed store, if owners are informed of the risks and how to avoid spreading disease and how to protect their own flocks.

Biosecurity at such locations is especially critical during an outbreak situation, such as the 2002-03 exotic Newcastle disease outbreak in California. Feed stores represent a valuable opportunity to conduct training and outreach to the poultry-owning public to help them practice better biosecurity and thus reduce the risk of disease in their flocks.

Swap meets and auctions may have poultry and/or other birds for sale and, similar to feed stores, can serve as a central meeting or collection point for backyard poultry owners. The same potential for spreading disease organisms from backyards to the swap meet or auction and subsequently to other backyard flocks exists as with feed stores.

Live birds may be bought and sold in these facilities and, therefore, the risk of spreading avian diseases through this mechanism is always present. Owners and vendors should be educated and made aware of this risk, and should be instructed in biosecurity methods to protect their flocks and their customers’ flocks.

Diverse workforce

Backyard poultry ownership is ubiquitous worldwide and widely prevalent within most, if not all, ethnic groups represented in the United States. This is especially true for the gamefowl culture which is thoroughly and irrevocably entrenched into the Hispanic population as well as many other cultures including Asian an Pacific Islander groups and a number of Caucasians.

Larger gamefowl holdings frequently have employed caretakers, in addition to the owners, to look after the birds. Employed gamefowl caretakers are predominately Hispanic. The ability to converse in the Spanish language is especially beneficial when dealing with the cockfighting industry.

For workers employed by the commercial poultry industry, ownership of other poultry or birds is strongly discouraged and usually forbidden. Likewise, bird ownership by employees of some larger backyard operations may be discouraged, but this stipulation is far more difficult or impossible to enforce. In any case, it is virtually impossible to preclude commercial poultry industry workers from having some degree of outside involvement in gamefowl activities. This connection to the gamefowl industry, therefore, represents an additional risk of disease introduction and/or spread from the gamefowl industry to commercial poultry facilities. Consequently, it is essential for poultry facility workers to consistently practice strict biosecurity methods. Many large commercial poultry firms require their employees to comply with a strict company biosecurity policy or face dismissal.

Business continuity

Protocols have been developed that detail the steps and time intervals to be followed to repopulate a commercial poultry enterprise after a depopulation event for control of an exotic disease (10). These protocols are, thus far, not applicable to backyard poultry owners whose flocks have been depopulated as a disease control method. Similar protocols should be developed to guide backyard operations in repopulation methods following an outbreak situation.

Animal disease traceability

Producers should contact their state animal health agency and determine the state requirements for registering their premises. This information is helpful in the event of an animal disease outbreak to notify producers with susceptible species. Individual animal identification requirements vary by state and may depend on the event if the birds are taken to shows or exhibitions.

Reference: "USDA APHIS | FAD Prep Industry Manuals". Aphis.Usda.Gov. 2013. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aph...

The manual was produced by the Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University of Science and Technology, College of Veterinary Medicine, in collaboration with the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service through a cooperative agreement.