US Poultry Industry Manual: scope of the turkey industry

Learn about the business of growing turkey businessPart of Series:

< Previous Article in Series Next Article in Series >

Editor's Note: The following content is an excerpt from Poultry Industry Manual: The Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (FAD PReP)/National Animal Health Emergency Management System (NAHEMS) Guidelines which is designed to provide a framework for dealing with an animal health emergency in the United States. Additional content from the manual will be provided as an article series.

Turkeys are primarily ground dwelling birds in the order Galliformes, family Phasianidae that are more closely related to pheasants than chickens. Domestication of wild turkeys took place in Mesoamerica prior to the arrival of Europeans in the New World. The origin of modern commercial turkeys can be traced to the Mexican subspecies of the wild turkey, Meleagris gallopavo gallopavo. Descendants of these early domesticated turkeys (Pavo creollo) can still be found in rural areas of southern Mexico, although breeding with reintroduced European strains has occurred. Domesticated turkeys from North America were exported to Europe shortly after colonization of the New World began, where they were bred for various characteristics and re-exported to other parts of the world including back to North America. Turkeys were highly prized for their meat qualities and were served on special occasions. It is believed that confusion with guinea fowl provided by merchants from Turkey, known as “turkey coq” in Europe, led to the name turkey, but other theories also exist. Crossing domestic European turkeys with the wild turkey resulted in a larger, more robust, colorful bird that became known as the Bronze turkey. The Broadbreasted Bronze turkey, developed through selection of Bronze turkeys for growth, became the worldwide standard for commercial turkey production until the 1950’s, when it was replaced by the Broad-breasted White turkey. Primary turkey breeding companies have continued to select breeding stock resulting in annual improvements in growth and feed efficiency (Smith, 2006).

Profitable production of turkey meat is the goal of the commercial turkey industry in the United States. The U.S. is the largest producer of turkey in the world accounting for just over half of the annual world production of 2.6 million metric tons followed by the European Union-27 member states. The U.S. also continues to be the largest consumer of turkey meat, but per capita consumption of turkey is highest in Israel at approximately 22 pounds/per person, followed by per capita consumption in the U.S. at approximately 17 pounds. Turkey is consumed

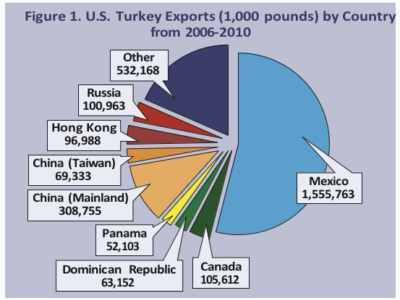

throughout the year, but consumption in the U.S. still peaks during the Thanksgiving and Christmas holiday season. Primary trading partners purchasing U.S. turkey were Mexico, China, Canada, Russia, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Dominican Republic, and Panama; Mexico accounted for over half of all turkey exports.

In many ways, the turkey industry is similar to the broiler industry as both use intensive management systems to achieve the goal of producing meat. However, there are differences including the way in which breeding stock is obtained and managed, length of time flocks are grown, production characteristics, physiologic differences, prevalence of backyard/niche flocks, and presence of a freeliving population of wild turkeys. The turkey is not merely an over-sized chicken; they are actually quite different from each other (Table 1).

Table 1. Differences Between Commercial Turkeys and Broilers |

|

Turkeys and chickens are much different from each other. Turkeys should not be thought of as just big chickens. |

|

TURKEYS |

BROILERS |

Breeding stock usually supplied as fertile eggs |

Breeding stock usually supplied as chicks |

Male and female breeders managed separately |

Male and female breeders commingled |

Reproduction by artificial insemination |

Reproduction by natural mating |

Larger adult ( ~26 lbs, ~50 lbs) |

Smaller adult ( ~7 lbs, ~12 lbs) |

Hens become broody if not controlled |

Broody control not important |

90 - 120 fertile eggs/hen |

150 - 175 fertile eggs/hen |

Larger, brown speckled eggs |

Smaller, light brown eggs |

28 day incubation period |

21 day incubation period |

Poults sexed at hatch |

Chicks not sexed at hatch |

Poults sexed by vent examination |

Chicks sexed by sex-linked feathering |

Servicing at hatch* |

Usually no servicing at hatch |

Separate hen and tom farms |

Sexes usually grown together on same farm |

Poults usually brooded in rings in brooder house |

Chicks brooded in section of production house |

Moved to separate housing for finishing |

Brooded and finised in same house |

Faster growth rate |

Slower growth rate |

Require higher protein starter (28%) |

Lower protein starter (18%) |

Feeds more expensive |

Feeds less expensive |

Free-living native turkeys |

No free-living chickens |

Processed at older ages (16-22 weeks) |

Processed at younger ages (6-9 weeks) |

More susceptible to disease |

Less susceptible to disease |

More resistant to avian paramyxovirus 1 |

More susceptible to avian paramyxovirus 1 |

More susceptible to avian influenza virus |

Less susceptible to avian influenza virus |

*See glossary under ‘Servicing’. |

|

Turkey Numbers and Location

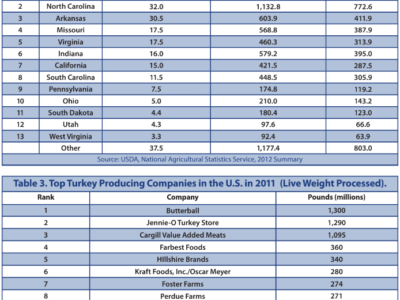

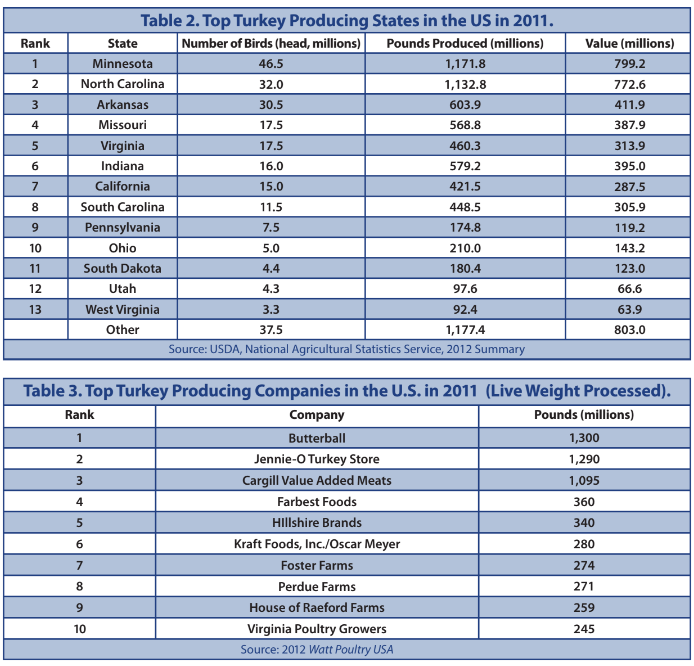

Approximately 260 million turkeys are grown in the U.S. annually. Most commercial production occurs in the North-central, Central, Mid-east, and Mid-Atlantic regions of the U.S., and California (Figure 2). Top turkey producing states in 2010 are listed in Table 2. In 2010, combined production of the top three states, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Arkansas, accounted for 43% of total U.S. production. Top turkey producing companies are listed in Table 3 and information about turkey companies in the U.S. can be found at http://www.poultryegg.org/ economic_data/docs/USTurkeyCompanies.pdf. Two genetic strains of turkeys are used for commercial production in the U.S.: Aviagen Turkeys (formerly Nicholas Turkeys), located in Lewisburg, West Virginia, and Hybrid Turkeys located in Kitchener, Ontario. A third strain, BUTA (British United Turkeys of America), is no longer marketed in the U.S. but is grown internationally as BUT. BUT breeding stock also is owned by Aviagen, Inc.

Turkey Production Systems

While the vast majority of turkeys in the U.S. are Broad-breasted White turkeys raised intensively for commercial meat production, other types of turkeys are kept for similar or different purposes.

Some turkey flocks are raised to preserve specific breeds. These are known as “Heritage Turkeys”. Some breeds are extremely rare with fewer than a hundred individuals known to exist. Recognized heritage breeds are those described in the American Poultry Association Standard of Perfection judging guide: Black, Bronze, Narragansett, White Holland, Slate, Bourbon Red, Beltsville Small White, and Royal Palm. Other color varieties also are often accepted as heritage breeds or are referred to as “Heritage-type” turkeys. Characteristics of heritage turkeys are an ability to mate naturally, long reproductive period, ability to thrive in free-range systems, and slow growth. Images of heritage turkeys can be found at http://www.porterturkeys.com4/ and http://albc-usa.org/cpl/wtchlist.html.

Small flocks of turkeys, usually heritage-type turkeys, are produced for specialty niche markets or direct sale. Management systems vary, but typically, heritage-type turkeys are raised seasonally for the holiday market with access to free-range and minimum confinement.

Occasionally turkeys are kept along with a menagerie of other birds in backyard flocks (see Chapter 4), but they are not common because turkeys are more expensive to maintain, require a higher level of management, can contract histomoniasis (a serious, often fatal disease) and Mycoplasma gallisepticum from chickens, have a lower reproductive potential, and do not produce marketable eggs. In addition to captive rearing of turkeys, production in many areas coincides with the range of free-living wild turkeys, making disease transmission between captive and free-living flocks possible.

Turkey Industry Structure

Most commercially raised turkeys are produced by vertically integrated companies that have one or more complexes. Less commonly, turkeys are produced by cooperatives formed by owners of the production facilities. However, cooperatives also own or control various steps in the production cycle and are vertically integrated.

Vertical Integration

Vertically integrated companies control multiple stages of the production cycle, which facilitates synchronization of scheduling to meet product demand and plan for future markets, removes middlemen, and integrates profit centers to maximize financial returns. Costs are spread over the entire production process. Not every stage has to generate a profit so long as overall production is profitable. For example, day-old poult costs may be higher for a superior strain of turkey, but these costs may be offset by increased productivity of the superior birds when they are grown. Maximizing profit by balancing inputs and outputs for each stage of production requires excellent supervisory skills and decision making.

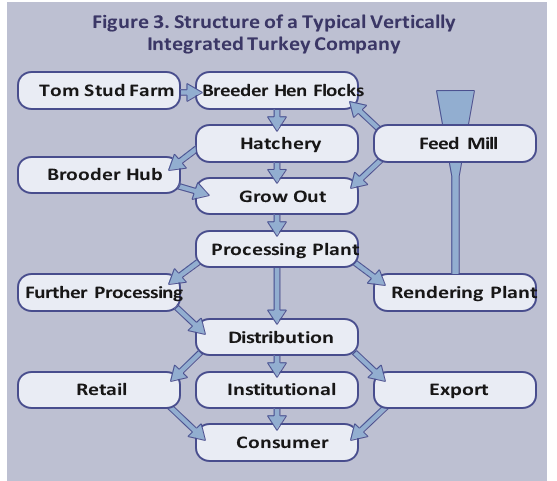

The degree of vertical integration varies among companies. Structure of a typical vertically integrated turkey company is shown in Figure 3. Each stage is managed as either a cost or a

profit center. A complex consists of a vertically integrated unit that usually includes breeders, hatchery, brooding, finishing, feed mill, and processing. Larger companies often have multiple complexes located in different geographic areas, either within a state or in other states. Production of around 12 million turkeys in a complex is considered optimum for resource utilization; however, the number of birds produced in a complex varies greatly among companies. Some integrated turkey companies also raise other commodity livestock such as broiler chickens or pigs because production of these animals is similar to that for turkeys, e.g., feed manufacturing and delivery, processing, and marketing.

How much a company actually owns in the integration and how much it controls through contractual arrangements differs among companies. When aspects of production are owned and operated by the company, critical stages such as breeding, which require close control and a high level of management, are more likely to be owned and operated by the company. Losses on the breeding farm have an impact throughout the whole company. Sometimes a company will own part of a production step, while the balance will be contracted.

Most finishing is done by contract producers who provide the facilities and labor in return for a contract price when the flock is marketed. Bonuses are provided for superior results in performance parameters including livability, growth, and feed conversion. The company owns the birds and provides feed, health care, and technical expertise for the birds. Service technicians, employed by the company, oversee the turkeys through regular visits to the flocks during which they monitor the flock’s progress and advise on management and health. Service technicians usually have formal post-secondary education or long-term experience raising turkeys. Sometimes they also have their own farm and flocks, which they grow under contract for the company. They are not permitted to have other types of poultry in any numbers or contract flocks with another company.

When depopulation is necessary, such as limiting spread of a foreign animal disease, it can become problematic as to how payments for compensation should be made. Payment for the birds is made to the company, but the producer also loses much of their income because of the depopulation. Usually an equitable solution is determined between the company and contract growers and may have been predetermined in the contract. Similarly, dead bird disposal can be an issue between the company and contract producer. The grower is responsible for the collection and disposal of mortality in the flock, which can be a considerable expense if mortality is high, especially when birds are older.

Economics

Both fixed costs for buildings, equipment, utilities, taxes, and mortgage payments, and variable costs including poults, labor, transportation, processing, health care, and feed go into the cost of producing turkeys. Feed accounts for approximately two-thirds of the cost of production. Prices for corn and soybean meal, the main feed ingredients, largely determine the cost of feed. Turkey feeds tend to be more expensive than feeds for broilers because of the higher protein and energy requirements for optimal turkey growth. Similarly, feeds for young birds, which have higher protein and lower energy, are more expensive than feeds for older turkeys, which have lower protein and higher energy. Overall feed costs in 2011 are over $300/ton and expected to rise further due to the high price of corn, soybean meal, and supplemental fat.

Turkey accounts for approximately 13% of income generated from the sale of poultry products in the U.S.. Between 2006 and 2010, around 260 million turkeys were raised annually in the U.S.. An average of 7.4 billion pounds live weight was produced that was worth an average of nearly 4 billion dollars. Price per pound averaged 53.6 cents. Per capita consumption averaged just over 17 pounds/person. Exports accounted for slightly more than 10% of processed turkey (Table 4).

Table 4. Annual Production of Turkey in the U.S. |

||||||

Year |

Head (millions) |

Pounds (billions) |

Value (millions) |

Price/lb (dollars) |

Export (%) |

Per capita Consumption |

2006 |

262.0 |

7,418 |

3,551 |

.479 |

547 (10.2) |

16.9 |

2007 |

266.8 |

7,566 |

3,954 |

.523 |

547 (10.9) |

17.5 |

2008 |

273.1 |

7.922 |

4,477 |

.565 |

676 (9.2) |

17.6 |

2009 |

247.4 |

7,149 |

3,573 |

.500 |

534 (10.6) |

16.9 |

2010 |

244.2 |

7,107 |

4,371 |

.615 |

583 (9.7) |

16.4 |

5 Year Average |

258.7 |

7,432 |

3,985 |

.536 |

577 (10.1) |

17.1 |

Source: USDA, Economic Research Service, National Agricultural Statistics Service |

||||||

Capital Investment

Construction of a new turkey finishing farm with four houses in the Southeastern U.S. will cost around $1.5 million dollars exclusive of land (a minimum of 20 acres [8.1 ha]), land preparation, a well to provide adequate water, and utilities. However, costs may vary considerably according to geographic location, type of housing, current market prices, and size of the farm. Houses are usually 40 to 50 feet (12.2-15.2 m) wide and 500 to 700 feet (152-213 m) long. Previously, houses were curtain-sided and relied heavily on natural ventilation, but current housing is closed (solid side-wall housing), heavily insulated, and tunnel ventilated with automated fans and controllers. Backup generators provide electricity in the event of a power failure. Contract prices per pound of turkey are generally range from 4.5-5.0 cents/lb live weight. Number of pounds of turkey produced annually depends on the type of management system (on-site or off-site brooding), size of the farm, and efficiency of production. Brooding of poults on-site or off-site affects contract prices. Many companies have moved to off-site brooding at farms called “brooder hubs”, especially for tom production, to maximize the biosecurity value of “All in/All out” production (see Section 2.4). Brooding off-site permits a greater number of flocks to be grown on a farm because 5 to 6 weeks of the growing cycle occur on the brooder hub. Hen flocks are usually marketed at 14-18 weeks weighing 14-18 pounds (6.4-8.2 kg) while tom flocks are marketed at 20-22 weeks weighing 40-44 pounds (18-20 kg).

Return on investment is also highly variable. Assuming a house has 25,000 ft2 (50 x 500 ft) [2323 m2 (15 x 152m)], hens are stocked at a final density of 2.5 ft2 (0.23 m2) per bird (10,000 hens), livability is 95% (9500 hens), average weight is 15 lbs (6.8 kg), grower pay is 4.5 cents per lb (9.9 cents per kg), and 4 flocks are produced with off-site brooding (~10 weeks for finishing and a minimum of 2 weeks downtime between flocks), the projected gross income would be (9500 hens x 4 flocks x 15 lbs x $.045) $25650. For toms, the same calculations (5625 toms [stocking at 4 ft2/bird x 90% livability] x 3 flocks x 41 lbs [18.6 kg] x $.045) would result in a projected annual gross income of $31,130. If the brooder hub also is managed as a contract operation, a contract price for the turkeys is provided for this phase of the production cycle based on livability or other production parameters. Contract growers of breeders are paid for number of eggs. Often this is specified to be settable eggs (normal clean eggs suitable for incubation) that can be used for hatching, rather than total eggs.

Allied Industries

Not only is the turkey industry a producing industry, it also is a consuming industry. The greatest input is feed; corn and soybeans account for 83-91 percent of total feed ingredients. The turkey industry consumes over 7.67 million tons of corn and 2.5 million tons of soybean meal annually. In Minnesota, the number one turkey producing state, corn and soybean consumption by the turkey industry is equivalent to the production of nearly 2000 grain farmers. Other inputs required by the turkey industry are housing and equipment, vehicles, additional feed ingredients, products for cleaning and disinfection, and health products including vaccines and pharmaceuticals. Many of these products are provided by industries allied to the turkey industry, which may also provide technical expertise to support use of their products. In areas where there are multiple integrated poultry or swine companies, formation of a cooperative to provide supplies to the companies at cost have been created.

Diverse Workforce

Most workers on commercial and breeder turkey farms are of foreign descent, especially Hispanic. Knowledge of conversational Spanish, or having a person of Hispanic descent on an investigative team, is helpful when trying to learn how flocks are actually being managed on a farm. Interviewing the producer and farm workers about biosecurity or other management practices often results in divergent answers. Gaining the trust of the farm workers is particularly helpful in the event that a foreign animal disease control program is needed. Workers in processing plants also often come from diverse backgrounds, more so than those that work on turkey farms.

Premises Registration and Traceback

Knowledge of the location, type, and size of turkey flocks is important for disease control, especially in the event of a foreign animal disease outbreak. Prompt diagnosis and rapid, effective containment is critical to minimize the economic impact of an outbreak. Each turkey company has excellent record systems and can track a flock from its breeder source to the lot in which it was processed. Subsequently, trace back of processed product to the company and flock of origin is possible by examining processing and production records. For security purposes there has been reluctance to integrate farm and flock information among companies, but this has been done in several states where turkey production is important (e.g., North Carolina). Access to these databases is strictly controlled and cannot be released. Cooperation between Federal and State agencies is in concert with the current United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) position on animal traceability (Animal Disease Traceability Framework: Comprehensive Report and Implementation Plan, USDA, 2011,

Vertical Integration

Vertically integrated companies control multiple stages of the production cycle, which facilitates synchronization of scheduling to meet product demand and plan for future markets, removes middlemen, and integrates profit centers to maximize financial returns. Costs are spread over the entire production process. Not every stage has to generate a profit so long as overall production is profitable. For example, day-old poult costs may be higher for a superior strain of turkey, but these costs may be offset by increased productivity of the superior birds when they are grown. Maximizing profit by balancing inputs and outputs for each stage of production requires excellent supervisory skills and decision making.

The degree of vertical integration varies among companies. Structure of a typical vertically integrated turkey company is shown in Figure 3. Each stage is managed as either a cost or a

profit center. A complex consists of a vertically integrated unit that usually includes breeders, hatchery, brooding, finishing, feed mill, and processing. Larger companies often have multiple complexes located in different geographic areas, either within a state or in other states. Production of around 12 million turkeys in a complex is considered optimum for resource utilization; however, the number of birds produced in a complex varies greatly among companies. Some integrated turkey companies also raise other commodity livestock such as broiler chickens or pigs because production of these animals is similar to that for turkeys, e.g., feed manufacturing and delivery, processing, and marketing.

How much a company actually owns in the integration and how much it controls through contractual arrangements differs among companies. When aspects of production are owned and operated by the company, critical stages such as breeding, which require close control and a high level of management, are more likely to be owned and operated by the company. Losses on the breeding farm have an impact throughout the whole company. Sometimes a company will own part of a production step, while the balance will be contracted.

Most finishing is done by contract producers who provide the facilities and labor in return for a contract price when the flock is marketed. Bonuses are provided for superior results in performance parameters including livability, growth, and feed conversion. The company owns the birds and provides feed, health care, and technical expertise for the birds. Service technicians, employed by the company, oversee the turkeys through regular visits to the flocks during which they monitor the flock’s progress and advise on management and health. Service technicians usually have formal post-secondary education or long-term experience raising turkeys. Sometimes they also have their own farm and flocks, which they grow under contract for the company. They are not permitted to have other types of poultry in any numbers or contract flocks with another company.

When depopulation is necessary, such as limiting spread of a foreign animal disease, it can become problematic as to how payments for compensation should be made. Payment for the birds is made to the company, but the producer also loses much of their income because of the depopulation. Usually an equitable solution is determined between the company and contract growers and may have been predetermined in the contract. Similarly, dead bird disposal can be an issue between the company and contract producer. The grower is responsible for the collection and disposal of mortality in the flock, which can be a considerable expense if mortality is high, especially when birds are older.

Economics

Both fixed costs for buildings, equipment, utilities, taxes, and mortgage payments, and variable costs including poults, labor, transportation, processing, health care, and feed go into the cost of producing turkeys. Feed accounts for approximately two-thirds of the cost of production. Prices for corn and soybean meal, the main feed ingredients, largely determine the cost of feed. Turkey feeds tend to be more expensive than feeds for broilers because of the higher protein and energy requirements for optimal turkey growth. Similarly, feeds for young birds, which have higher protein and lower energy, are more expensive than feeds for older turkeys, which have lower protein and higher energy. Overall feed costs in 2011 are over $300/ton and expected to rise further due to the high price of corn, soybean meal, and supplemental fat.

Turkey accounts for approximately 13% of income generated from the sale of poultry products in the U.S.. Between 2006 and 2010, around 260 million turkeys were raised annually in the U.S.. An average of 7.4 billion pounds live weight was produced that was worth an average of nearly 4 billion dollars. Price per pound averaged 53.6 cents. Per capita consumption averaged just over 17 pounds/person. Exports accounted for slightly more than 10% of processed turkey (Table 4).

Table 4. Annual Production of Turkey in the U.S. |

||||||

Year |

Head (millions) |

Pounds (billions) |

Value (millions) |

Price/lb (dollars) |

Export (%) |

Per capita Consumption |

2006 |

262.0 |

7,418 |

3,551 |

.479 |

547 (10.2) |

16.9 |

2007 |

266.8 |

7,566 |

3,954 |

.523 |

547 (10.9) |

17.5 |

2008 |

273.1 |

7.922 |

4,477 |

.565 |

676 (9.2) |

17.6 |

2009 |

247.4 |

7,149 |

3,573 |

.500 |

534 (10.6) |

16.9 |

2010 |

244.2 |

7,107 |

4,371 |

.615 |

583 (9.7) |

16.4 |

5 Year Average |

258.7 |

7,432 |

3,985 |

.536 |

577 (10.1) |

17.1 |

Source: USDA, Economic Research Service, National Agricultural Statistics Service |

||||||

Capital Investment

Construction of a new turkey finishing farm with four houses in the Southeastern U.S. will cost around $1.5 million dollars exclusive of land (a minimum of 20 acres [8.1 ha]), land preparation, a well to provide adequate water, and utilities. However, costs may vary considerably according to geographic location, type of housing, current market prices, and size of the farm. Houses are usually 40 to 50 feet (12.2-15.2 m) wide and 500 to 700 feet (152-213 m) long. Previously, houses were curtain-sided and relied heavily on natural ventilation, but current housing is closed (solid side-wall housing), heavily insulated, and tunnel ventilated with automated fans and controllers. Backup generators provide electricity in the event of a power failure. Contract prices per pound of turkey are generally range from 4.5-5.0 cents/lb live weight. Number of pounds of turkey produced annually depends on the type of management system (on-site or off-site brooding), size of the farm, and efficiency of production. Brooding of poults on-site or off-site affects contract prices. Many companies have moved to off-site brooding at farms called “brooder hubs”, especially for tom production, to maximize the biosecurity value of “All in/All out” production (see Section 2.4). Brooding off-site permits a greater number of flocks to be grown on a farm because 5 to 6 weeks of the growing cycle occur on the brooder hub. Hen flocks are usually marketed at 14-18 weeks weighing 14-18 pounds (6.4-8.2 kg) while tom flocks are marketed at 20-22 weeks weighing 40-44 pounds (18-20 kg).

Return on investment is also highly variable. Assuming a house has 25,000 ft2 (50 x 500 ft) [2323 m2 (15 x 152m)], hens are stocked at a final density of 2.5 ft2 (0.23 m2) per bird (10,000 hens), livability is 95% (9500 hens), average weight is 15 lbs (6.8 kg), grower pay is 4.5 cents per lb (9.9 cents per kg), and 4 flocks are produced with off-site brooding (~10 weeks for finishing and a minimum of 2 weeks downtime between flocks), the projected gross income would be (9500 hens x 4 flocks x 15 lbs x $.045) $25650. For toms, the same calculations (5625 toms [stocking at 4 ft2/bird x 90% livability] x 3 flocks x 41 lbs [18.6 kg] x $.045) would result in a projected annual gross income of $31,130. If the brooder hub also is managed as a contract operation, a contract price for the turkeys is provided for this phase of the production cycle based on livability or other production parameters. Contract growers of breeders are paid for number of eggs. Often this is specified to be settable eggs (normal clean eggs suitable for incubation) that can be used for hatching, rather than total eggs.

Allied Industries

Not only is the turkey industry a producing industry, it also is a consuming industry. The greatest input is feed; corn and soybeans account for 83-91 percent of total feed ingredients. The turkey industry consumes over 7.67 million tons of corn and 2.5 million tons of soybean meal annually. In Minnesota, the number one turkey producing state, corn and soybean consumption by the turkey industry is equivalent to the production of nearly 2000 grain farmers. Other inputs required by the turkey industry are housing and equipment, vehicles, additional feed ingredients, products for cleaning and disinfection, and health products including vaccines and pharmaceuticals. Many of these products are provided by industries allied to the turkey industry, which may also provide technical expertise to support use of their products. In areas where there are multiple integrated poultry or swine companies, formation of a cooperative to provide supplies to the companies at cost have been created.

Diverse Workforce

Most workers on commercial and breeder turkey farms are of foreign descent, especially Hispanic. Knowledge of conversational Spanish, or having a person of Hispanic descent on an investigative team, is helpful when trying to learn how flocks are actually being managed on a farm. Interviewing the producer and farm workers about biosecurity or other management practices often results in divergent answers. Gaining the trust of the farm workers is particularly helpful in the event that a foreign animal disease control program is needed. Workers in processing plants also often come from diverse backgrounds, more so than those that work on turkey farms.

Premises Registration and Traceback

Knowledge of the location, type, and size of turkey flocks is important for disease control, especially in the event of a foreign animal disease outbreak. Prompt diagnosis and rapid, effective containment is critical to minimize the economic impact of an outbreak. Each turkey company has excellent record systems and can track a flock from its breeder source to the lot in which it was processed. Subsequently, trace back of processed product to the company and flock of origin is possible by examining processing and production records. For security purposes there has been reluctance to integrate farm and flock information among companies, but this has been done in several states where turkey production is important (e.g., North Carolina). Access to these databases is strictly controlled and cannot be released. Cooperation between Federal and State agencies is in concert with the current United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) position on animal traceability (Animal Disease Traceability Framework: Comprehensive Report and Implementation Plan, USDA, 2011, http://www.aphis.usda.gov/trac...).

Interstate movement of poultry, including turkeys, also will be covered under the new traceability regulation. Unless exempted, each lot or group of birds will be identified by an Interstate Certificate of Veterinary Inspection (ICVI) issued by a Federal, State, or accredited veterinarian. Exemptions to the regulation can be found in the 2011 Animal Disease Traceability Plan. In this plan, poultry will be identified by sealed and numbered leg bands according to National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) regulations, a group identification number, or other means agreed to by State or Tribal officials. A timeline for implementing the traceability plan for poultry has not been established.

Reference: "USDA APHIS | FAD Prep Industry Manuals". Aphis.Usda.Gov. 2013. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aph...

The manual was produced by the Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University of Science and Technology, College of Veterinary Medicine, in collaboration with the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service through a cooperative agreement.