Shelterbelts: Has Their Time Come ?

By G.T. Tabler, Poultry Science Department at the University of Arkansas's Avian Advice - The increasing urban expansion into rural areas creates numerous challenges for livestock producers to various types of farming operations. A strong livestock industry is essential to the nation’s economic stability, the viability of many small rural communities, and the sustainability of a healthful, plentiful and high quality food supply for the American public.Introduction

Farmers and

ranchers view odors and dust associated with

livestock as part of production agriculture and

have come to accept them as part of their way

of life. However, as urban dwellers are less

likely to accept dust or odors, differences in

lifestyles between farmers and city folks are

becoming increasingly apparent. Although

there will probably always be some odor and

dust issues associated with animal production

units, there are some simple, economical

methods of reducing the frequency of

complaints.

For poultry producers, shelterbelts offer

an opportunity for poultry growers to be

proactive in demonstrating good neighbor

relations and environmental stewardship.

Shelterbelts are typically vegetation (most

often trees and shrubs) planted in purposeful

rows to alter wind flow in order to achieve

certain objectives. Planting trees and shrubs

as screens around poultry houses will help

remove them from public view (perhaps also

the public’s mind) and buffer odor, dust and

noise.

Livestock Production

In the United States about 130 times more

animal waste is produced annually than

human waste. Livestock in the U.S. produce

more than 1.4 billion tons of manure annually

(U.S. Senate Committee, 1997). Livestock

production in the U.S. is characterized by

fewer yet much larger production facilities.

USDA data indicate that nationwide about

85% of estimated 450,000 agricultural

operations with confined animals have fewer

than 250 animal units (GAO, 1995).

Therefore, only about 15% of farms

house the vast majority of the animal units

nationwide. USDA estimates that only about

6,600 animal feeding operations nationwide

have more than 1,000 animal units (GAO,

1995). From 1978-1992, the average number

of animal units per facility increased by 56,

93, 134, 176, 148 and 129% for cattle, hogs,

layers, broiler and turkeys, respectively, while

during the same period the number of

facilities dropped by over 40% in the cattle

industry, and over 50% in the dairy, hogs and

poultry industries (USDA and EPA, 1999).

Figure 1 demonstrates the increase in broiler

production and decrease in broiler farm

numbers from 1975 to 1995. Increased size

of production facilities and greater numbers

of livestock at each facility has meant larger

amounts of animal waste, concentrated into

relatively smaller geographic areas. This

concentration of animals has increased the intensity, duration, and timing of odor events. The control of livestock odors has become of paramount concern for the public and

livestock producers.

Figure 1: US Broiler production (lbs) and number of farms 1975 - 1995 Source: United States Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry, 1997 |

Understanding Odor Events

A recent survey of Iowa farmers found that 46% of rural residents were within a half mile or less of a livestock facility. In the same survey 71% of residents were within one mile of a livestock facility (Lasley and Larson, 1998). This finding is consistent with the average separation distances nationwide (Tyndall and Colletti, 2000). Odor compounds may be transmitted as gases, aerosols (a suspension of relatively small solid or liquid particles in gas) or dust (relatively large particles in gas or air). Efforts to control odors from animal production units fall into three basic strategies (Tyndall and Colletti, 2000):

- Prevent odors from forming

- Capture or destroy odorous compounds and

- Collection, dispersion or dilution of odor compound.

In most cases the third strategy is the easiest and most economical procedure to implement in animal production units. In operations without protection wind or breezes often transmit odors gases, aerosols and dust to neighbors. Shelterbelts hinder this transmission, by trapping odors, redirecting air or creating turbulence so that odor compounds are diluted.

Odor Control using Shelterbelts

The source of animal odors is near the ground and tends to

travel along the ground (Takle, 1983), shelterbelts can

intercept and disrupt the transmission of these odors (Heisler

and DeWalle, 1988; Thernelius, 1997). Shelterbelts also

reduce the release of dust and aerosols by reducing wind speed

near production facilities. Wind tunnel modeling of a threerow

shelterbelt quantified reductions of 35% to 56% in the

downwind transport of dust. However, shelterbelt density

determines the degree to which dust and aerosols are reduced.

Density is a simple ratio of the porous area (the areas wind can

pass through) to the total area of the shelterbelt. A density of

approximately 40-60% is the most beneficial (Brandle and

Finch, 1991). The trees or shrubs chosen for the shelterbelt

and the spacing of those plants will determine the overall

density. Remember that deciduous species tend to be more

open closer to the ground and conifers have branch cover

close to the ground (Griffith, 2001).

Shelterbelts physically also intercept dust and other

aerosols. A forest cleans the air of micro-particles twenty-fold

better than barren land. Leaves with complex shapes and large

circumference to area ratios collect particles most efficiently.

Shelterbelts attract and bind the chemical constituents of odor.

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) have an affinity to the

cuticle of plant leaves. Microorganisms on plant surfaces can

metabolize and breakdown VOCs.

Finally, shelterbelts provide a visual and aesthetic screen.

A well-landscaped livestock operation is much more

acceptable to the public than one that is not. Shelterbelts

should be designed for the specific location, according to the

expected and experienced odors, so that the tree and shrub

species chosen can provide year round interception of odors

and aerosols (Griffith, 2001).

Why Shelterbelts Now

Although shelterbelts have been used for many years in

the Midwest to modify wind flow; control wind erosion,

increase crop yields, protect farm buildings, and protect

livestock, few in poultry producing areas considered their use.

However, urban encroachment is forcing changes in how

poultry growers manage their operations and tunnel ventilated

houses have made the use of shelterbelts feasible. Few

recommended planting trees around poultry facilities for fear

of blocking air flow through conventionally-ventilated houses,

but today, with the poultry industry shifting to tunnelventilated,

solid sidewall poultry houses, restricting natural air

flow is much less of a problem.

Trees have a pleasing image across a large cross section of

the American population. Planting trees around poultry

houses may help foster a positive image of your farming

operation. In addition, as the trees mature, less of your

agricultural operation will attract attention, your farm takes on

a more attractively landscaped appearance, and property

values increase for both you and your neighbors (Malone and

Abbott-Donnelly, 2001).

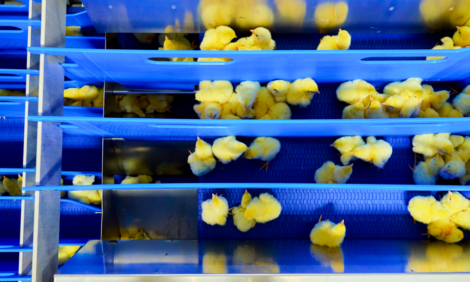

Plants used in Shelterbelts

Dense evergreen trees are perhaps the best choice for the

tunnel fan end for maximum filtering during summer and

screening year round. For greatest emissions scrubbing,

shelterbelts should be as close to the tunnel exhaust as

possible. As a general rule, to not interfere with fan

efficiency, no trees should be planted closer than a distance of

five times the diameter of the fans (Malone and Abbott-

Donnelly, 2001). Check with your integrator before

constructing a shelterbelt. Take into account the width of the

shelterbelt at maturity and how this may affect roads, loadout

areas, or chick delivery areas.

There are a variety of trees and shrubs suitable for

Arkansas conditions that would work well to screen poultry

houses. White pine, properly spaced, creates a dense

shelterbelt, grows rapidly and is reasonably priced. Virginia

pine and loblolly pine also do well. Various cedars also form

a dense mat; however, some consider certain varieties a

nuisance and the berries may attract wild birds. A variety of

hollies and other ornamental shrubs such as Red Tip Photinia

form highly effective screens and have a beautifying effect on

the surrounding landscape. The plants you choose will depend

on the site, soil conditions, available space, number of plants

required, growth rate of plants, personal preference for

landscaping effects and cost of the plants. For more

information on trees and plants that do well in your area,

contact your local county Extension office, local Conservation

District, Arkansas Forestry Commission or a professional

landscape nursery/garden center.

Air quality issues surrounding poultry production facilities

are no longer a matter of “if”, but “when.” Arkansas poultry

producers should take proactive steps to plan for management

changes these issues will bring. The planting of trees in

strategic locations around poultry houses is one method to

help address these issues before and as they arise. In addition,

research has shown that shelterbelts can reduce heating costs

10-40% and reduce cooling costs as much as 20%.

Strategically placed trees can also reduce wind speeds by

50%, adding protection from spring and fall storms. The

leaves of trees physically trap dust particles that may be laden

with nitrogen, and root systems will absorb up to 80% of the

nutrients that might escape the proximity of the poultry

operation (Stephens, 2003). Cost-share assistance for planting

a shelterbelt is available in some states; unfortunately,

Arkansas is not one of these states at the present time.

Barriers to Shelterbelt Adoption

Although shelterbelts around the perimeter of poultry houses offer many advantages, there are some barriers to adoption and some negative aspects to consider. For example, Malone and Abbott-Donnelly (2001) indicate:

A limited amount of land will be taken out of production to support the shelterbelt

There will be cost associated with purchasing the trees, labor for planting and maintenance

You will encounter a restricted view of your houses access will be limited to designated roadways trees will create a potential habitat for wild birds.

Summary

Air quality issues will become an increasing concern to

production agriculture with continued urban encroachment

into previously rural, agricultural areas. Shelterbelts offer one

method by which poultry producers can take proactive steps to

address the issue; demonstrating good public relations efforts

and environmental stewardship by buffering odor, dust and

noise emissions from their facilities while improving farm

aesthetics and property values.

Dense shelterbelts may detract

attention from farming operations and help reduce air

emission concerns surrounding poultry facilities by capturing

dust particles and ameliorating odors. Consult your integrator

concerning placement before constructing a shelterbelt. Select

trees or shrubs suitable for your area. Your local Extension

office, NRCS office, Arkansas Forestry Commission or local

landscape nursery can be of valuable assistance on species

information. If planted during warmer weather, be sure to

provide plenty of water to assure successful establishment. A

well-landscaped livestock operation is more pleasing to the

public than one that is not.

A shelterbelt used as a pollution

control device is visible proof that producers are making an

effort to control what leaves their operation. This could prove

valuable in the court of public opinion and perhaps reduce

tension levels between farming and non-farming segments of

the population.

References

Brandle, J. R., and S. Finch. 1991. How windbreaks work.

University of Nebraska Cooperative Extension Publication

EC91-1763-B.

General Accounting Office (GAO). 1995. Animal

Agriculture: Information on Waste Management and Water

Quality Issues.

Griffith, C. 2001. Improvement of air and water quality

around livestock confinement areas through the use of

shelterbelts. South Dakota Association of Conservation

Districts.

Hammond, E. G., C. Fedler, and R. J. Smith. 1981.

Analysis of particle bourne swine house odors. Agriculture

and Environment. 6:395-401.

Heisler, G. M., and D. R. Dewalle. 1988. Effects of windbreak structure on wind flow. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.,

Amsterdam. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 22/23:41-69.

Laskley, P. and K. Larson. 1998. Iowa farm and rural life poll – 1998 Summary Report. Iowa State University Extension, Pm-

1764, July, 1998

Malone, G. W., and Abbott-Donnelly, D. 2001. The benefits of planting trees around poultry houses. University of Delaware

College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Bulletin #159. 4 pages.

Stephens, M. F. 2003. Benefits of trees on poultry farms. The Litter Letter. Fall 2003. LSU Ag Center Research and Extension,

Cooperative Extension Service. Calhoun, La.

Takle, E. S. 1983. Climatology of superadiabatic conditions for a rural area. J. Climate and Applied Meteorology. 22:1129-

1132.

Thernelius, S. M. 1997. Wind tunnel testing of odor transportation from swine production facilities. M. S. Thesis. Iowa State

University, Ames.

Tyndall, J., and J. Colletti. No Date . Odor Mitigation. Available at: http://www.forestry.iastate.edu/res/odor_mitigation.html.

6 pages.

Tyndall, J., and J. Colletti. 2000. Air quality and shelterbelts: Odor mitigation and livestock production a literature review.

Source: Avian Advice - Winter 2004 - Volume 6, Number 2