US Poultry Industry Manual - turkey brooding

Brooder housing, turkey developmentPart of Series:

< Previous Article in Series Next Article in Series >

Editor's Note: The following content is an excerpt from Poultry Industry Manual: The Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (FAD PReP)/National Animal Health Emergency Management System (NAHEMS) Guidelines which is designed to provide a framework for dealing with an animal health emergency in the United States. Additional content from the manual will be provided as an article series.

Brooding is the period after hatching during which a turkey poult requires supplemental heat. The term also is used when the poult is in the brooder house. Brooding is done in a house specifically designed for this purpose. Poults are usually allocated at least one ft2 (0.1 m2) per bird. They are usually restricted in brooding rings during the first few days of life. The brooding period encompasses the first 5-6 weeks of the turkey production cycle.

Brooder Houses

Preparations for brooding begin as soon as the previous flock in the house has been removed. Litter and all organic material are removed and insecticides or other control measures for darkling (litter) beetles (Alphitobius diaperinus) are applied while they are still active. Over the next several days, the house, entry way and surrounding areas, equipment, water lines, feed lines, and feed bins are thoroughly cleaned and disinfected. Fans, timers, lighting, alarms, curtains or air inlets, and other equipment are similarly inspected to insure they are in good working order. After cleaning, the house is closed and left vacant. The sooner the house is prepared, the longer the down time before the new flock arrives. A minimum down time of 10 days is recommended, but longer times are preferred to permit microbes in the house to die.

Fresh, clean, dry litter (usually kiln-dried pine shavings) is delivered to the farm and spread evenly over the floor to a depth of 3-4 in (7.6-10.2 cm). A spray may be applied to the surface of the litter to help reduce fungal spores and other contaminants. Brooder equipment is checked several days before placement and any repairs made. Brooder stoves should have a blue flame and cycle appropriately in response to changes in temperature settings. A yellow flame indicates incomplete combustion, which generates carbon monoxide. Carbon monoxide above 20 ppm is detrimental to poults and people working in the house. Pancake or pan brooders are usually set at 24 in (61 cm) but may be raised or lowered slightly to obtain optimal litter temperatures. Brooders must always have a safety chain to prevent them from accidentally falling into the litter, and propane lines need to be checked with soapy water for leaks. Radiant tube heating systems mounted on the ceiling are used in some newer brooder housing. They rely less on heating circulating air than traditional pan brooders. Regardless of the type of brooding equipment, it needs to provide even, appropriate house temperatures at the level of the poults.

At least one day before placing the poults, fresh feed is delivered to the farm and the house is set up. It is important to use fresh feed, as it will stimulate the poults to eat. Circular or oval brooder rings, 12-14 ft (3.7-4.3 m) in diameter and 12-18 in (30.5-45.7 cm) high made of new corrugated cardboard are placed in the litter around each pan brooder. Single brooder rings are sufficient for around 300 poults. Some growers use an oval double ring that is suitable for more poults and surrounds two or more conventional pan brooders. Larger rings also are used for radiant heat brooder stoves. In houses with radiant tube heating, birds may be placed directly in the house with cardboard only used to round the corners of the house to prevent piling of poults for the first few days. Conventional and supplemental feeders and drinkers are radially arranged about midway between the brooder equipment and wall of the ring and completely filled with fresh feed and water. Poults are provided with at least 1 in (2.5 cm) of drinker space and 1.25 in (3.2 cm) of feeder space. Nipple drinkers are becoming more common and are replacing traditional bell drinkers. For starting poults, cups on nipple drinkers should be filled.

Brooders are lit the day before poults arrive to warm the food, water, litter, and house to the desired environmental temperature. Temperatures of the litter under the brooders and at the edge of the ring should be checked with an infrared gun to be sure they are between 100-115°F (38-46°C) and 75-85°F (24-29°C) respectively. It is important to have a 20-30°F (9-15°C) gradient between the center and edge of the ring to allow each poult to locate its own comfort zone. House temperatures are more uniform when radiant tube heating is used. Ventilation fans are adjusted to run a minimum of one minute out of five minutes. Thermostat fans are set to run when target temperatures exceed 2°F (1°C). Poor ventilation results in weak, inactive poults that do not start well. Ammonia and carbon dioxide levels above 25 ppm and 2500 ppm respectively are detrimental to the poults. Measurements of gases need to be at bird level to be meaningful. A carbon monoxide detector can be taken into the house when poults are being checked first thing in the morning to determine if toxic levels exist, but dust may interfere with its operation if it is left in the house continuously. Lighting needs to be uniform with an intensity of 50-70 lux.

On the day of placement, poults are delivered early in the morning so they have the full day to adjust to their new surroundings and begin eating and drinking, which are critical to the poults getting a good start. Poults must drink or they will not eat. Equal numbers of poults are allocated per ring. They are gently transferred from poult boxes to the rings and given a short interval to spread out and acquaint themselves with their new environment. Dead or cull poults are removed and may be saved by refrigeration or freezing for possible future diagnostic use. If there are no significant disease problems in the first few days after placement, cull and dead poults that have been saved can be discarded. As a general rule, the earlier poults die after placement, the more likely the problem came from the hatchery or breeder flock; conversely, the later they die, the more likely the farm environment was the source of the disease.

While the birds need to be checked frequently the first day and night, conditions in the house need to remain as quiet and calm as possible. Poults are curious and gather along the side of the ring in response to sounds or activity in the house. This is detrimental, as they need to be learning to eat, drink, and find their comfort zone. Poults often sleep off and on during much of the first day, but by the second day, they should be active and evenly distributed. Clustering of poults under a brooder or along the edge of the ring indicates that conditions are too cool or hot respectively and need to be checked and adjusted. Poults in one spot away from the heat source indicate a possible draft. Poults receive constant light on the first day.

During the next few days, poults continue to be checked frequently; drinkers are adjusted to compensate for litter compaction and average poult size, cleaned, and kept filled. After poults are drinking well, the depth of water in the drinkers can gradually be reduced to decrease spillage and soiled litter. Spilled or soiled feed is removed and feeders adjusted and refilled. Feeders are generally kept completely filled for the first couple of weeks. Height of drinkers and feeders is adjusted to be at the level of the poults’ shoulder. Soiled litter that accumulates around drinkers and feeders is either tilled into adjacent good litter or removed and replaced. Light duration is reduced to provide a period of at least one hour of darkness so the poults will not panic if there is an electrical failure.

Poults are more challenging to start than chicks. They have little available energy reserves when they hatch and must rapidly switch from a lipid-based to a carbohydrate-based metabolism by synthesizing glycogen from protein via gluconeogenesis. Attempts to assist in this process through nutrition have not been successful. Weak poults, undersized poults, and “flip-overs” (poults that get over on their backs and cannot right themselves) are removed and either culled or placed into a “hospital” pen where they have access to fresh feed and water, but a lower temperature. A few poults never learn to eat or drink. Sometimes they can be recognized because they still have the egg tooth, which normally is knocked off when a poult begins to eat. Occasionally it is possible to teach them by dipping their beaks into water and feed, but most often, they die of starvation. Such birds are called starve-outs and are found mainly between 4-6 days of age. Starve-outs occur more frequently in poults that come from young breeder flocks. Poults in the hospital pen that recover can be returned to the rest of the flock.

A common practice is to combine two pens together after 3-5 days and remove them altogether by 7 days. Cardboard that formed the rings is discarded. In some instances, it may be helpful to put cardboard in the corners of the house to round them out for a few more days to prevent piling. Similarly, any open containers (e.g., buckets) or equipment should be taken out of the house to prevent poults from getting into them and smothering each other. Supplemental drinkers and feeders are gradually removed as the poults learn to use the equipment that will remain in the house. For turkeys, it is important that this change be made gradually over 3 or 4 days. Temperatures under the brooder and in the house are reduced by approximately 5°F (2.8°C) weekly until they match ambient temperatures, and ventilation is increased to control litter moisture, ammonia, and dust levels in the house.

Poults grow rapidly during the remainder of the brooding period. It is important to check them at least twice a day, and to adjust feeders and drinkers to the correct height and depth every few days. Feeders and open drinkers are adjusted to shoulder height so that poults need to slightly bend their head and neck over the edge of the feeder or drinker to eat or drink. Birds should be able to walk under feeders and drinkers. If feeders and drinkers are raised too high, the birds can irritate their necks when they eat or drink, which can lead to a form of persecution (“cannibalism”) called neck picking. Litter needs to be raked daily or removed to prevent buildup of cake along feed lines and around drinkers. Mortality is picked up at least twice daily, recorded, and disposed of by burning, composting, or rendering depending on state regulations and availability. If mortality exceeds a certain threshold (commonly one bird per 1000), and there is no obvious cause, a diagnostic investigation may be indicated during which fresh dead and clinically affected turkeys are examined to establish a diagnosis. Vaccination for hemorrhagic enteritis is done between 4-5 weeks of age in most turkey flocks; other vaccinations may be given via water or spray if indicated. Vaccinations should be completed at least one week prior to the turkeys being moved to finishing.

On-farm Brooding

Until the past 15 years, almost all turkeys were brooded in a separate brooder house, constructed and equipped for brooding, on the same farm where they were grown and finished. These are called ‘brood and grow’ farms. Both two- and three-stage production systems evolved to maximize utilization of housing and equipment on the farm, and amortize fixed costs over maximum production. In multi-stage production systems, two or three flocks of different ages are always on the farm. This makes disease control difficult as older flocks on the farm serve as reservoirs of infectious agents for the younger birds. Spread of disease from older flocks on the farm to the next flock as it was placed led to infection in younger birds, increasing severity of disease because of early exposure, increased exposure, and passage through successive groups of birds. On-farm brooding is still done, especially for hen flocks, but it is becoming less common as the industry moves to off-site brooding.

Two-stage systems have a brooder house matched with either two or three finishing houses. Typically there are two finishing houses for hen production and three finishing houses for tom production, but there is farm-to-farm variability. The brooder house is divided into two sections for hens or three sections for toms. Turkeys in one section of the brooding house usually populate one finishing house. At around 5 weeks of age, turkeys in each section are slowly walked through temporary corridors constructed of wooden panels and stakes, or, less commonly, a permanent breezeway, from the brooder house to a finishing house. Turkeys are easily moved using “flags” - poles with one or more strips of plastic or cloth attached to the end. In the finishing houses, hens and toms receive at least 2 or 3 ft2 (0.2 - 0.3 m2) of floor space respectively, which accounts for the brooder: finishing house ratios of 1:2 for hens and 1:3 for toms. After the brooder house is vacated, it is cleaned, disinfected, and prepared for the next flock, which arrives before the older flock on the farm has been processed. Larger farms have multiples of this same 3 or 4 house design.

Double brooding is a variation of two-stage production used for growing tom flocks. The longer cycle for toms allows two flocks of turkeys to be brooded for two finishing house units. These farms typically have one brooder house and 6 finishing houses or their equivalent (e.g., 4 larger houses with floor space equivalent to 6 conventional sized houses). Each finishing unit needs to have at least 3 times the floor space of the brooder house. While technically a two-stage system of production, this system has many of the same disadvantages of three-stage production including three age groups on the farm, continuous production on the farm, and minimum downtime between flocks in the brooder house. Health problems tend to be greater on these farms, similar to those of farms using three stages of production.

Efficiency of the two-stage system declined as hens grew faster and were marketed as whole birds at younger ages and toms were held longer and marketed for further processing (“cut-up”) at older ages. Either there was inadequate turn-around time in the case of hens, or the brooder house sat idle for an extended period for tom flocks. This ushered in the 3-stage production system for tom turkeys, again designed to maximize use of housing and equipment. In this system, production is divided into 3 stages – brooding (0-5 weeks), intermediate (6-11 weeks), and finishing (12-18 weeks). Brooding and intermediate stages are done in a single house. One-third of the house is used for brooding, while the remainder is used for the intermediate stage. The two parts are separated by a solid partition with doors that can be opened. Ventilation flows from brooding to intermediate sections to conserve heat from the brooding end of the house, and it is simple to move birds from brooding to intermediate by opening the partition, turning lights on in the intermediate section, and turning them off in the brooding section. Birds naturally migrate to the lighted section of the house. Finishing takes place in separate houses on the same farm similar to that in 2-stage production.

While both two- and three-stage production systems make economic sense, they violate the basic “All in/All out” principle of biosecurity. In these production systems, either two or three flocks are on the farm at the same time, and there is never a time when the farm is completely depopulated. Especially problematic is the 3-stage system where two different flocks are in the same barn. As enteric diseases such as turkey coronaviral enteritis, poult enteritis complex, and poult enteritis mortality syndrome (PEMS) emerged as serious problems in the turkey industry, controlling them on multi-stage farms became difficult to impossible. Losses from disease soon outweighed the economic advantages of staged growing. While some staged growing still exists, especially for hens, three-stage production is probably no longer practiced, and two-stage production is becoming less common.

A couple of single-stage variants of on-farm brooding are occasionally done on older ‘brood and grow’ farms. One single stage management system is similar to production of broiler chickens. The house is divided by a removable partition (often a drop curtain) into two parts. Typically about one-half or one-third of the house is used for brooding hens and toms respectively. When brooder stoves are no longer needed at around 3-4 weeks, the partition is removed and the flock has the entire house where they stay until they are processed. Separate feed lines for younger and older birds are needed, but a single water line is usually adequate. This production system is best suited to growing light hens. It is possible to produce three hen flocks, but only two flocks of toms annually in this production system. With either type of turkey, this system still lacks economic efficiency compared to multi-stage growing.

The other single stage production system has similarities to multi-stage production systems. Poults are brooded in one or more brooding houses on the farm. When they reach 5-6 weeks of age, most of the birds are moved to other houses on the farm, but some of the birds remain in the brooder houses. In this way, all of the birds on the farm are a single age, but there are empty houses on the farm with longer down time while the poults are brooding and therefore there are greater overhead expenses. Also, this is usually not done with tom turkeys, as the equipment used in the brooding houses is not adequate for growing toms to processing.

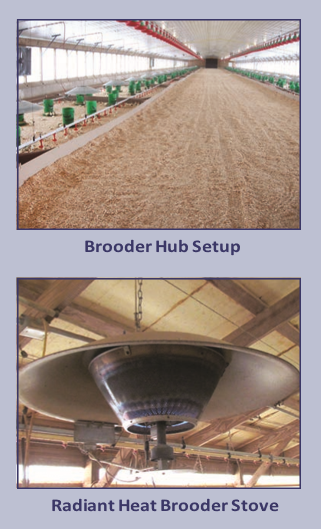

Off-site Brooding (Brooder Hubs)

To capture the health advantages of “All in/All out” production and economic benefits of multi-staged growing, many companies have moved to off-site brooding. These farms only brood turkeys and are commonly called “brooder hubs”. Brooder hubs are most efficient for producing toms because of their longer production cycle and higher value at processing, which can be divided between brooding and finishing farms. One brooder hub can provide poults for two groups of tom finishing farms. Having a facility dedicated solely to brooding permits a high level of biosecurity, intense management focused on the needs of the young turkey, quantity purchases of supplies, especially propane, and total clean out between flocks. Poults are delivered to the brooder hub, grown to 4-5 weeks of age, loaded into transport coops, and taken to several finishing farms where they are grown to processing. Determining the average weight when poults are transferred from the brooder farm to the finishing farm and dividing it by their age in days provides the overall average daily gain for the brooding period. In addition to livability, average daily gain is an excellent way to monitor how well poults grew during brooding and the measure correlates well with how they will process. After turkeys have been removed from the brooder hub, it is thoroughly cleaned, disinfected, and prepared for the next flock.

Disadvantages of this production system are the stress of moving the turkeys from the brooder hub to finishing farms, possibility of trauma during loading and unloading, and that several finishing farms could be adversely affected if the poults experience a disease on the brooder hub that depresses their growth and development. The abrupt change in environment during transfer often sets the turkeys back for a few days as they re-learn how to get food and water and re-establish their social interactions. It is common for them to lose up to 10% of their body weight during moving and the first few days after being placed into the finishing farm. They generally regain this lost weight before they are processed.

Physiological Development of Poults

Turkey poults are precocial and may seem developed at hatch, but actually, they are still immature and require several weeks to develop completely functional body systems. An example is the immune system, which will not be capable of fully responding to an antigen until the turkey is around 6 weeks of age. Vision is poorly developed at hatching, which may help explain why poults have difficulty finding food and water after hatching. Consumption of feed as soon as possible after hatching is important as this initiates development of the digestive and immune systems and stimulates the absorption of yolk, which contains maternal antibodies and nutrients essential for early growth (Halevy et al., 2003).

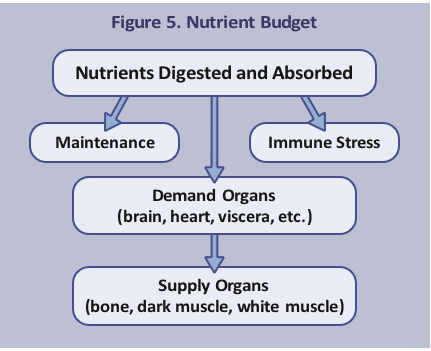

It is important to understand the “nutrient budget” as it pertains to poult growth and development (Figure 5). Prior to hatching, everything required by the turkey embryo to develop into a poult comes from the hen via the egg. After hatching, everything required by the turkey to maintain itself and grow comes from nutrition via the digestive system. This includes feed intake, digestion, absorption, and assimilation at the cellular level. Early growth and development of the digestive system is several times greater than the body as a whole.

Organs of the digestive tract, along with those critical for survival (immune, cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous, and special senses) comprise the “Demand” organs. Nutrients are preferentially supplied for maintenance, response to immune stresses, and demand organs. When the digestive system is functioning normally, supply organs also are provided with nutrients, based on the needs of the developing poult, to the skeletal system, dark muscles, and lastly white muscles. If nutrients are not adequately provided by the digestive system because of inadequate feed intake or enteric disease, a greater proportion of the nutrient budget shifts from the supply organs to deal with immune stress and provide for the demand organs. This results in stunting, poor skeletal development, and reduced muscle and ultimately meat, especially white meat, at processing. If nutrients are not available, as in severe disease and anorexia, muscle is catabolized to provide for maintenance, immune stresses, and minimum nutrients essential for survival. These birds become runted, rarely ever recover, and need to be culled.

Growth of turkeys is rapid. At hatching, poults weigh around 60 g, while toms have an average weight of 20.5 kg when they are processed at 20 weeks of age. Thus, male turkeys increase their original body weight over 340 times in a period of 140 days; an average of nearly 2.5 times their initial weight every day. Growth rates of hens are similar, but not as rapid, and they are marketed earlier at lower body weights. Failure to grow, even for a few days, becomes obvious because of the high growth rate, which leads to poor flock uniformity.

Reference: "USDA APHIS | FAD Prep Industry Manuals". Aphis.Usda.Gov. 2013. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aph...

The manual was produced by the Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University of Science and Technology, College of Veterinary Medicine, in collaboration with the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service through a cooperative agreement.