US Poultry Industry Manual - turkey movement

poultry delivery, transfer to finishing, load-out and transfer to processingPart of Series:

< Previous Article in Series Next Article in Series >

Editor's Note: The following content is an excerpt from Poultry Industry Manual: The Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (FAD PReP)/National Animal Health Emergency Management System (NAHEMS) Guidelines which is designed to provide a framework for dealing with an animal health emergency in the United States. Additional content from the manual will be provided as an article series.

Various segments of the turkey industry are constantly on the move. While this is necessary for producing the turkeys, it also increases the risk of spreading infectious agents. For breeding, semen is collected and taken from the stud farm to the hen breeder farms for insemination. Crews responsible for cleaning and disinfection, vaccination, load-out, transfer of turkeys from brooding to finishing, and insemination move among farms to do their work. Service technicians travel to farms to oversee production, advise on management and health, conduct pre-placement audits to make sure brooder houses are properly prepared, and assist with placement of poults. Ideally, farm visits by service technicians are limited to two a day, but often it is necessary for them to check more flocks. Any farms with disease problems are done last, unless it is an emergency.

Day-old Poult Delivery

Flocks are assembled in the hatchery as poults complete servicing. After resting overnight in the holding room, poults are loaded into a special poult transport vehicle (sometimes called a “poult bus”) that provides ventilation and a temperature controlled environment for the poults during the move. Proper ventilation is critical to the health of the poults. Loading of poults is done early in the morning and they are taken to the farm where they will be placed. Poults can tolerate long shipping distances that last a day or more, but for most companies, farms are usually located within 2 hours of the hatchery. After poults have been delivered, the poult delivery vehicle is cleaned, disinfected, and prepared for the next delivery. Poult delivery depends on the hatching schedule, but typically they are delivered to farms on Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday.

Transfer to Finishing

In staged production, turkeys are simply walked from the brooding house to the finishing house as described previously. However, now that most brooding is done off-site, the birds must be loaded into coops at the brooder hub and taken to the finishing farm. Placing turkeys into coops at the brooder hub is similar to the way turkeys are loaded out for processing (see 4.3) except the trailers on which the coops are mounted are lower to the ground, coops have less headroom, and coops can be tilted hydraulically. At the finishing farm, turkeys are off-loaded by backing the trailer into the house, opening the coop doors, raising the back of the coop so that it tilts outwardly, and allowing the turkeys to slide out of the coops onto the litter.

Load-out and Transfer to Processing

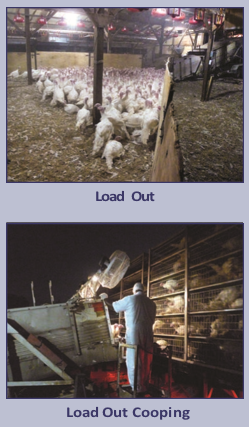

Load-out is done using a special machine called a “turkey loader” that has a conveyor belt for transferring turkeys from the house to coops mounted on a live-haul truck trailer. The turkey loader can be raised and lowered to adjust to the different levels of coops. On the day the flock is to be removed from the farm, the loader is hauled to the farm where it is placed just inside an end door of the finishing house where transfer of the turkeys will take place. The other end is placed alongside the coops on the live-haul truck when it arrives. A catch pen, constructed with movable panels and stakes, funnels the turkeys into the loader in the house. Turkeys are gently driven into the catch pen where they move onto the conveyer belt, which takes them to the coop. Individuals referred to as “coopers” stand on either side of the loader and move the turkeys into the coops. Coordinating movement of the truck and loader makes it possible to move the turkeys into coops with minimum handling. The number of turkeys per coop depends on their type and size, size of the coop, environmental conditions, and distance to the processing plant. Typically, coops are in 5-7 levels and range in height from 14-19 in (36-48 cm).

Steps in Processing

At the processing plant, trailers with coops loaded with turkeys are placed into a holding shed where air is circulated by large fans and misting may be used if temperatures are high. Trailers are pulled into the plant when it is time for the birds to be processed. The location and height of the trailer is periodically adjusted to permit turkeys to be manually removed from the coops and hung by their feet and legs in shackles that are attached to a moving chain. The area is kept darkened and a bar contacts the breast of the birds to help keep them quiet, reduce wing flapping, minimize distress, and reduce parts condemnations due to hemorrhages, bruising, or broken wings. The chain moves the birds into the stunning area and bleed-out tunnel where they receive an electrical shock with alternating current (150-200 m/amps, 90 volts, 10-15 seconds) to induce unconsciousness followed by severing at least three of the four major vessels in the neck. Birds die of cerebral anoxia before they regain consciousness. Blood drains from carcasses as they move through the tunnel to the scald tank, where they are immersed in hot water (~140°F, 60°C) for 2-2.5 minutes, after which they go to pickers that remove feathers with a set of whirling rubber fingers. When defeathering has been completed, shanks are removed by cutting the legs through the hock joints and carcasses are rehung by the head and legs on a separate chain referred to as the evisceration line. Having two separate chains to interrupt the flow of carcasses through the plant between defeathering and evisceration is necessary to prevent carcasses from being held in the scald tank if the evisceration line has to be stopped.

Evisceration begins with a circular cut around the vent and vacuuming of the terminal gut contents, followed by a J-cut in the body wall and drawing of visceral organs out of the carcass. Automation is becoming more frequent in turkey processing plants, but it is still less common than in broiler processing plants. Carcasses and viscera are inspected by a USDA inspector, and parts judged to be adulterated are removed and condemned. Carcasses are either passed, passed with trimming done by plant personnel, removed from the line for reprocessing, or condemned. Reprocessing to clean up a carcass or remove parts to be condemned is done either on the reprocessing line or at special stations, depending on the reason the carcass was removed from the processing line. Reprocessing may occur for fecal or crop content contamination, bile staining, bruises, fractures, airsacculitis, or osteomyelitis. Green discolored livers are used at processing as an indicator of osteomyelitis.

Plant personnel remove the giblets and do any final trimming before the carcass enters the chiller where the internal temperature will be lowered to ≤40°F (4.4°C). After chilling, the carcass is either bagged, along with a giblet pack for sale as a whole bird, or cut up for further processed products. Generally, hens are sold as whole birds and toms provide cut up products and other manufactured foods. Processing yields for turkeys range from 81 to 83% for light hens and toms respectively. Value-added turkey products are increasing, but are not as common as chicken products, largely because turkey has yet to become a staple for fast-food markets. Once processing has been completed, product is stored frozen at a maximum temperature of 0°F (-17.7°C) until it is shipped. Minimum temperature for product to be sold as fresh (never frozen) turkey is 26°F (-3.3°C).

An alternative to electrical stunning is use of controlled-atmosphere stunning. In this procedure, coops of birds travel through chambers containing mixtures of gas comprised of carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and argon. Anoxia results in either unconsciousness or death. This method is considered to provide welfare benefits and is being used more frequently in Europe, but there are technical issues associated with it and it has not been widely adopted in the U.S.

Reference: "USDA APHIS | FAD Prep Industry Manuals". Aphis.Usda.Gov. 2013. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aph...

The manual was produced by the Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University of Science and Technology, College of Veterinary Medicine, in collaboration with the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service through a cooperative agreement.