What are farm residues worth?

Converting broiler dung and dry poultry manure into cashPoultry farmers focus on the production of eggs and meat for the consumer. However, keeping poultry also produces residues such as dry poultry manure and broiler dung. These residues – or would it be better to call them by-products or co-products? – have been moving further into the centre of attention (in Germany) for some time now. The reason: the nutrients and organic matter they contain make them increasingly valuable (see Table 1). This is a welcome development, especially for poultry farmers in regions with a high density of livestock, because they can turn the unwelcome residues into an attractive by-product.

Mean nutrient contents of farm-produced fertilisers (fresh matter)

Source: https://www.raiffeisen.com/pfl... (as at 9 August 2024)

| Solid manure | DM content (%) | N (kg/m³, t) | P₂O₅(kg/m³, t) | K₂O (kg/m³, t) |

| Turkey manure (in tonnes) | 50 | 19,1 | 18,1 | 16,4 |

| Duck manure (in tonnes) | 30 | 4 | 3 | 11 |

| Goose manure (in tonnes) | 30 | 8 | 6 | 11 |

| Broiler manure (in tonnes) | 55 | 28 | 21 | 23 |

| Chicken manure (in tonnes) | 30 | 18,1 | 12,5 | 10,4 |

| Chicken manure (in tonnes) | 60 | 29,9 | 22 | 20,2 |

| Poultry manure | ||||

| Fresh poultry manure (in tonnes) | 28 | 17 | 11,4 | 10 |

| Dry poultry manure (in tonnes) | 50 | 25,5 | 20,1 | 17,5 |

| Dried poultry manure (in tonnes) | 70 | 32 | 27,7 | 22,8 |

Versatile use

Farmers can utilise their farm-produced manure in a variety of ways to contribute to the farm profits with additional revenues. The amount and sustainability of this contribution is largely in their own hands. For example, farmers can use some broiler manure as a valuable organic fertiliser on their own farmland. This reduces the costs for mineral fertilisers and increases the humus content of their soil.

Farm-produced manure is very much in demand in regions with a low density of livestock: contractors specialising in the trade and supply of organic fertilisers collect the manure from regions with a high density of livestock and deliver it to regions with a low density of livestock. In the past, broiler farmers often either had to pay a small amount of money for this service or handed over their manure without earning anything.

War on Ukraine

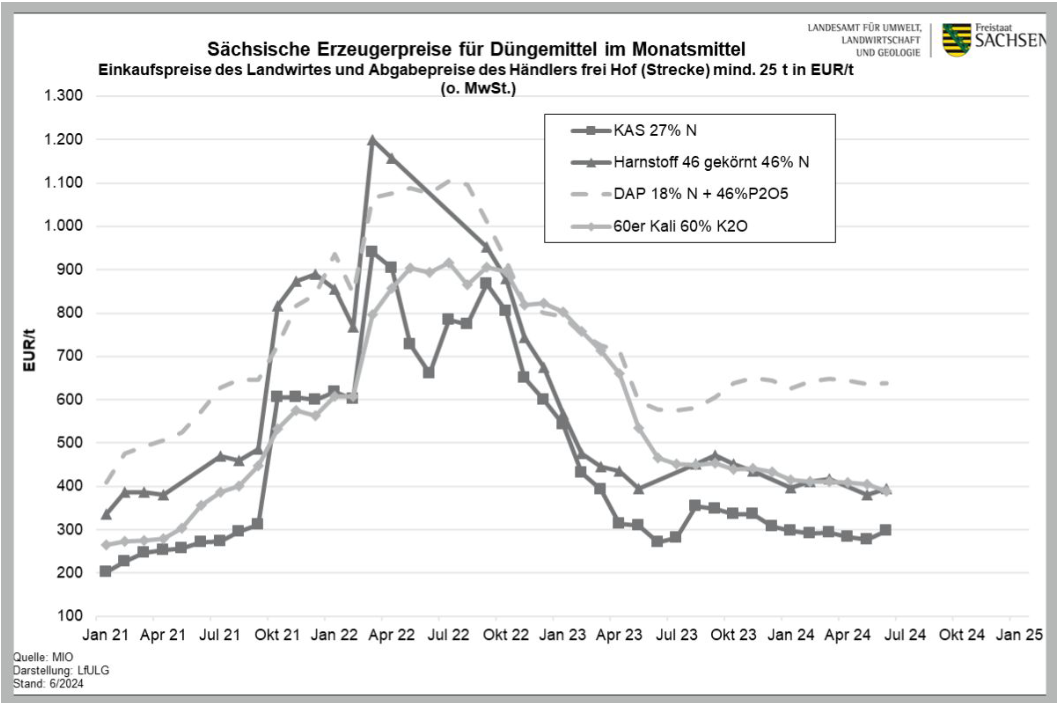

With the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the resulting energy crisis, prices for mineral fertilisers rose sharply (see Chart 1). At the same time, dry poultry manure and broiler dung were suddenly in high demand. Farmers were often able to sell their manure at very good prices. Prices have currently calmed down again. In the longer term, they are likely to stabilise at a slightly higher level than before the energy crisis.

The EU agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by a minimum of 55 per cent by 2030 compared to 1990, and to make Europe climate-neutral by 2050, plays an important role for the question “How much are my residues worth?”. The EU agreement means that the use of fossil fuels will become more and more expensive; by 2050, fossil fuels should no longer be used at all.

Especially in broiler production, however, houses must be heated to around 33 °C when the day-old chicks are first moved in, which is a very energy-intensive period. The most common fuel today is still natural gas. But what can broiler producers do to reduce their energy costs while also contributing to climate-neutral production? There is no simple answer to this question considering the complexity of the issue.

Efficient and sustainable: circular economy

One keyword for the answer: circular economy. Farmers who operate a biogas plant alongside their broiler production are in the comfortable position of being able to heat their poultry houses with the generated waste heat, and they can also produce electricity from the biogas. This reduces the use of fossil fuels (often natural gas) and enables farmers to utilise poultry manure for their own sustainable production of biogas.

The nutrients remain almost entirely in the digestate, which is therefore well suited as a fertiliser on arable land and grassland. For the correct determination of fertiliser requirements, the digestate must always be tested for its respective nutrient content, however.

Not all broiler producers have a biogas plant – nor do they have to, because they can sell their manure to biogas plant operators. This procedure has long been common in agrarian regions, especially, and is becoming increasingly important now. The reason is the rising price for maize, which causes the operators of biogas plants to turn towards less expensive options.

In addition, the large-scale cultivation of maize for use in biogas plants is viewed very critically – because where maize grows, no food can be grown, according to the general opinion.

From this point of view, the 150 m3 to 200 m3 of biogas per tonne of fresh matter from the animal alternative is not bad at all.

Versatile biomethane

And development continues, with the keyword being biomethane production. In addition to generating electricity from biogas, switching from the previous on-site power generation to biomethane production can be an interesting option. This applies in particular to larger plants and to those for which the so-called EEG remuneration expires after 20 years. Based on the German Renewable Energy Sources Act, operators of biogas plants received this remuneration for feeding electricity into the grid.

Biomethane has the great advantage that it is chemically identical to natural gas and that it can be fed into the existing gas grid. Biomethane can thus be used for electricity and heat generation as well as in the fuel market.

But what exactly does this mean for the poultry manure? Around 250 plants throughout Germany produce biomethane, and the number grows every day. These plants can also use poultry manure as input material, and plant operators are quite prepared to pay for this manure. It may make sense to conclude longer-term contracts.

Conclusion:

The relevance of poultry manure is changing from being considered an “annoying” residue to being perceived as a valuable by-product, especially in regions with a high density of livestock. Manure can be spread on the fields as a traditional fertiliser or be used to produce biogas.

To achieve the climate targets mentioned at the beginning, however, biomethane will become increasingly important for the fuel sector – particularly when it originates from “residues” such as poultry manure.

If farmers produce biomethane themselves, either individually or as a group, the greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction quota means that another aspect should be kept in mind: Companies that sell CO2-emitting fuels in Germany, i.e. diesel and petrol, must compensate for the greenhouse gas emissions that are produced when these fuels are burned, for example by buying GHG quota shares. Biomethane producers can sell these GHG quota shares to greenhouse gas distributors in the fuel sector, such as Shell.

China

Despite the many positive prospects for the domestic biomethane market, there is also a catch: If large amounts of biofuel are imported from China and then marketed in Germany, falsely labelled as “climate-friendly” within the scope of the Renewable Energy Directive II (RED II), this does not comply with the original intention of this directive.

Most of the Chinese biofuels do not come from residues, but are produced from palm oil – and yet German petroleum companies can still fulfil their obligation to reduce greenhouse gases in this manner. This means that the domestic biomethane value chain is no longer competitive, which has a significant impact on the revenues generated by poultry manure.