Few regions in the world are without IB virus

variants, he said. “In many countries, you have

three, four or five variants. We’re realizing that it

may be futile to vaccinate against one specific IB

virus strain. You have to try and make smart vaccine

combinations so your protection is broader.”

While IB variants can cause respiratory disease,

the greater concern in layers is a drop in egg

production and poor egg quality; in breeders, a

drop in hatchability might also occur. False layers

and nephritis are other possible consequences

of IB, De Wit said.

Low Titers = Poor Protection

Because they are long-lived birds, layers and

breeders need long-term IB protection. Live IB

vaccines can provide good protection but only for

a short period of time; they result in low antibody

titers, which correlate with low protection during

the laying period. Killed vaccines are required for

long-term protection but work much better if they

are administered after birds have received a live

vaccine first as a primer, he explained.

De Wit cited published, controlled studies

conducted by other investigators demonstrating

that layers not vaccinated against IB have the most

severe drop in egg production — above 70%.

A group vaccinated at 3 and 16 weeks of age with

a killed IB vaccine but no live primer had a drop

in egg production of about 30%, while a group

vaccinated with a live IB Massachusetts-strain

vaccine at 3 weeks of age then with a different live

IB Massachusetts-strain vaccine at 16 weeks of

age had about a 10% drop in egg production.

Even better results occurred in birds vaccinated

once with a live IB vaccine at 3 weeks of age,

followed by an inactivated IB vaccine at 15 weeks

of age. This group had no drop in egg production,

he said.

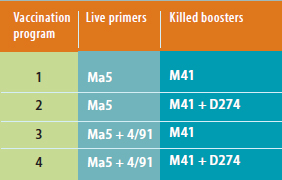

De Wit also presented the results of studies he

and colleagues conducted testing four IB vaccine

combinations against four Chinese Q1 IB strains

obtained from Latin America in 2009 and 2010. The

primer was either a live Massachusetts (Ma5) IB

strain or Ma5 plus a live IB 4/91 variant, which is

prevalent in Europe, followed by killed boosters

with IB M41 alone or with IB D274

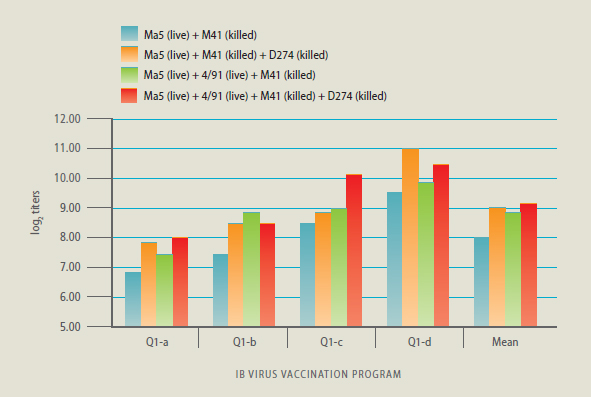

“The lowest level of virus-neutralizing antibodies

against this Q1 strain occurred when only a live

Massachusetts-strain (Ma5) vaccine and a boost

with inactivated M41 was used. On average, the

most complicated system of broad, live-vaccine

priming then a broad-boosting killed vaccine had

the best results and yielded the highest level of

neutralizing antibodies,” De Wit said.

Broad, Heterologous Bosting

“There are exceptions, but the message is usually

the same. It’s highly recommended, especially in

areas with a high IB challenge, that inactivated

vaccines be used to get more protection against

IB and, in general, that more vaccine strains be

used to achieve broad, heterologous boosting,”

De Wit said.

He also advised using a good, live, priming vaccine

before killed vaccines are administered to increase

the efficiency of the killed vaccines.

Even though good IB protection requires more

complicated vaccine programs, the good news,

he said, is that not every IB variant needs a vaccine

specifically for that variant. “By making smart

vaccine combinations, you can solve your

problems with a few vaccines.”

In addition, De Wit noted, “Producers quite often

complain that vaccination isn’t working because

there’s still a drop in egg production of about 5%,

but without vaccination, that drop could have

been 50%, 60%, 70% or even 80%.”

Vaccine Efficacy

Efficacy with IB vaccines, he pointed out, will

be affected by the strains of IB virus that are

administered, by the quality of each antigen per

dose and by the adjuvants used in each vaccine.

Proper vaccine application is imperative, De Wit

emphasized. In addition, trials conducted with

live IB vaccines have demonstrated that efficacy

improves if the ventilation system is turned off and

the lights are on. If the vaccine is administered in

water, there needs to be good water quality, low

in temperature and free of pathogens.

“Keep in mind that you are working with a very

sensitive virus that’s easy to kill. If you’re aware of

that, you’re on the path to better results,” he said.

Diagnostics

De Wit is a “big fan” of diagnostics when IB is

suspected. “Even if there are no problems, I think

it’s a good idea to obtain serological testing at the

end of each flock just to see if titers are high for IB,

because that means there was a challenge.”

It also means that the vaccination schedule was

working. The information can help producers

decide whether they should continue doing

what they’re doing, or that their program needs

adjusting, he said.

Certainly, he said, samples should be taken for

testing when there are clinical problems. “It’s very,

very easy to make incorrect conclusions if you don’t

obtain diagnostics. Maybe it’s not IB or it’s some

unexpected variant. If you don’t know that, plans

for the next flock will be wrong.”

Asked about the role of co-existing disease, De Wit

said that flocks with infections such as mycoplasma,

pneumovirus or other health problems are not

necessarily more susceptible to IB — but the

clinical signs after the IB infection will be more

severe and the recovery will be harder.

More Issues