Recent research findings in the US are providing further evidence that broilers can be protected from new infectious bronchitis variants with a protocol featuring two existing vaccines.

The studies, conducted by the University of Georgia, also revealed a strong correlation between clinical signs, ciliostasis and virus detection, indicating that it’s important to consider these three parameters when evaluating cross-protection with infectious bronchitis (IB) virus vaccines.

In 2011, a new, variant IB virus — known as GA11/GPL90/11 (GA11) — was isolated from broilers in north Georgia. The isolate was not related to any viruses used in commercially available vaccines. Molecular virologist Mark Jackwood, PhD, and colleagues designed a challenge study to determine whether they could use what is called a “PROTECTOTYPE protocol” to protect broilers from the new variant.

Added protection

Even though different serotypes of the IB virus generally do not fully cross-protect, there are “gray areas,” Jackwood says, noting that some IB serotypes are serologically related to other serotypes “just enough to provide cross-protection.” Each is called a “PROTECTOTYPE.”

Furthermore, previous research by Jackwood and European investigators has demonstrated that when a live IB vaccine from one serotype is followed by vaccination with an IB variant from another serotype, birds develop immunity to the serotypes in the vaccines — in addition to cross-reacting antibodies to other IB serotypes. The result is broader protection than what either vaccine can provide on its own.

Study protocol

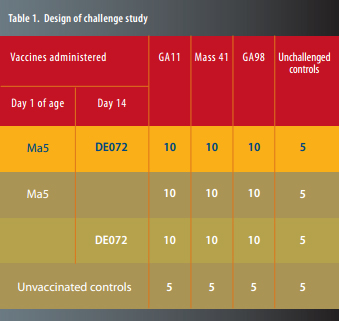

For the challenge study, researchers split the broilers into three groups with different vaccine protocols (Table 1):

- IB Ma5 vaccine at day 1 of age plus a IB DE072 on day 14 of age

- IB Ma5 vaccine on day 1

- IB DE072 vaccine on day 14

The IB Ma5 vaccine is based on the major Ma5 virus serotype, while the IB DE072 vaccine contains a variant of the Delaware IB virus. For controls, birds from each vaccination group were vaccinated but not challenged, while another group was not vaccinated and was challenged.

[In Europe and Latin America, a similar protocol using an Ma5 vaccine on day 1 plus vaccination with IB 4/91, a variant common throughout Europe, has been shown to protect against several IB-virus variants; 4/91 vaccines are not licensed for use in the US, however, so investigators replaced it with the DE072 vaccine.]

Investigators gave each bird a full dose of each vaccine, half by eyedropper and the rest by intranasal application. They then challenged the vaccinated birds with the viruses at 35 days of age with infectious doses.

Clinical signs of IB include mild upper-respiratory-tract disease such as sneezing, tracheal rales, gasping and coughing. In layers, IB can also result in decreased egg quality and production. Some strains of the IB virus, a coronavirus, cause kidney lesions. IB viruses can result in 100% morbidity. Mortality varies and is worse if there are other, co-existing infections such as Escherichia coli.

Understanding IB variants

A serotype is a virus characterized by its neutralizing antibodies that are specific to that virus.

Variants can be a new serotype or an existing virus that has undergone changes in the amino acid sequence of its spike protein, which is on the surface of the virus and may induce neutralizing antibodies.

After the IB virus was first recognized in the early 1930s in the US, the Massachusetts serotype was the only known serotype of the virus for about 15 years.

Today, there are more than 20 recognized serotypes and countless variant IB viruses. In the US, Arkansas remains the most isolated type of IB virus and it is undergoing genetic drift.

Illustration Above:

IB shows a number of characteristic spikes on its

surface. These consist of proteins and play an important

role in the onset of infection and the corresponding

immune response.

Results

For their study, Jackwood and his team considered birds protected from IB if there was > 90% protection from clinical signs, over 50% protection against ciliostasis and > 90% against virus detection. (The ciliostasis test involves microscopic observation; investigators then score the level of ciliary activity.) Based on these criteria, vaccinated broilers were protected against GA11, Mass 41 and GA98, he says.

“For birds that were clearly protected and birds that were not clearly protected, there was a strong correlation between clinical signs, ciliostasis and virus detection,” Jackwood reports. For partially protected birds, virus detection was always positive, but clinical signs and results with ciliostasis were variable.

“Based on these data, it appears that it is important to measure clinical signs, ciliostasis and virus detection when evaluating cross-protection in IB virus-vaccinated birds,” he said.

In addition, a protocol utilizing existing vaccines appears to provide a method of protecting poultry against several of the IB-variant viruses circulating now in different geographic areas and can alleviate the need for development of new vaccines for every new IB variant that emerges, which would be time consuming and costly.

He notes that maternal antibodies to IB viruses provide homologous protection for 1 or 2 weeks and do not appear to interfere with vaccination.

More Issues