Tossing around the 'S word'

Back in the 1970s, the word "sustainability" was used mainly by environmental groups to promote the conservation of natural resources while curbing pollution and waste.

That definition has held up well over the years and has proved to be, well, pretty sustainable. But as the term comes into wider use, it begins to mean much more to more people and more industries. It depends on their values, interests and beliefs.

For the sake of establishing a baseline for this article, let's turn to the popular UN definition, which describes it as "meeting the needs of the present, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

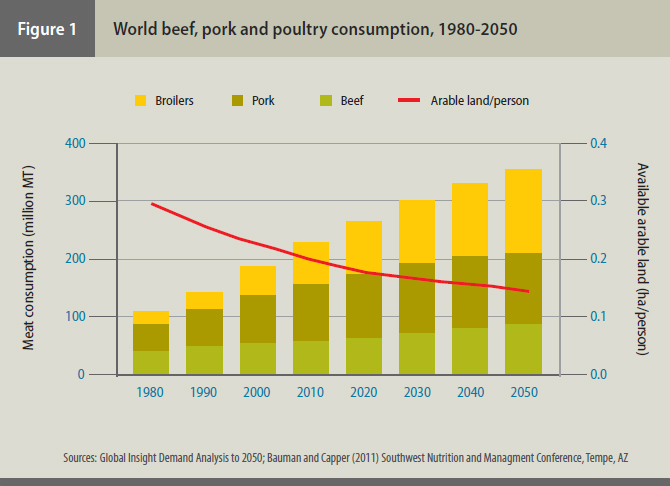

In agriculture, this generally translates to producing more with less — a goal that morphs into a dire need when looking at global population trends. According to a recent UN report, food production will need to increase by 70% to feed the world's 9.6 billion people by 2050 — a little more than 35 years from now — while limiting greenhouse gases and the need for additional land and water.2 That's a super-sized order.

Furthermore, sustainability experts say, agriculture needs to meet this goal by balancing economic viability with social and environmental stewardship. The big question is how.

Advantages for poultry

Fortunately for the industry, poultry production already has considerable advantages over other livestock systems in terms of energy efficiency, carbon emissions, feed conversion, land and water use, and waste.

Factor in poultry's high nutritional value, relatively low cost and universal palatability and it's no wonder that poultry is expected to continue to top the charts for meat consumption and production for decades to come, both in the US and abroad.

To manage this growth responsibly, some commercial US poultry farms are working to increase production on existing land, while minimizing pressure on the environment — an approach that is known as "sustainable intensification."

Maintaining good poultry health is critical to this strategy, as it directly affects human and animal welfare, economic viability and environmental impact — the very cornerstones of sustainable production. How the industry keeps its flocks healthy is also the subject of heated debate, however. As producers work to optimize bird health and performance in intensified settings, they also must answer to an inquisitive public that is increasingly concerned with how birds are raised and what goes into their feed and water.

Some see this as a challenge — not least because consumer perceptions of sustainability don't always reflect the realities of efficient, high-volume commercial production. Ask typical American consumers what "sustainable poultry" means and they'll probably describe poultry and eggs produced under a wide range of alternative systems — organic, free-range or antibiotic-free, to name a few. In response, a growing number of retailers and foodservice companies are adopting these consumer-driven standards as well.

Sound alternatives?

These trends have prompted the rapid growth of new production systems, which in many ways have been good for the industry. Consumers have more choices, and producers benefit from higher margins and robust demand for niche products. But is the rise of organic, free-range and antibiotic-free poultry actually making the industry more sustainable?

Not necessarily, says Stephen Shepard, a poultry specialist at Farm Animal Care Training and Auditing (FACTA), which audits, assures and implements animal-welfare programs for producers internationally.

Shepard supports alternative production practices; in fact, he routinely consults with poultry operations that want to produce birds "raised without antibiotics" — a more accurate description than the popular "antibiotic-free" — to establish successful and sustainable programs. However, he does not believe that approach is necessarily more sustainable than conventional practices. In fact, he says, the risks to animal welfare, food safety and efficiency tend to be much higher in these alternative systems.

"The practice of never using antibiotic feed additives results in higher feed conversions, higher production costs and, if not managed properly, more sick birds," Shepard explains. "This is not only a serious welfare issue, but it also results in a higher bacterial freight for poultry coming into the processing plant, which increases the risk of contaminated meat."

For these reasons, Shepard believes that judicious antibiotic use is critical to both poultry and human health — not only to control and prevent disease, but also to ensure the ethical treatment of animals. But it shouldn't always be necessary to wait for birds to get sick to start using antibiotics, he says. In many cases, he thinks it is actually more judicious — and more sustainable — to use antibiotics under veterinary supervision before they get sick.

"Antibiotic feed additives help maintain a healthy gut by controlling bacteria that are malignant to overall gut health, and a healthy gut leads to better absorption of nutrients," he reasons. "As a result, we get better feed conversions. And when we get better feed conversions, we promote sustainable agriculture through more efficient land and water usage."

Resisting resistance

Critics of using antibiotics to improve flock performance argue that these products may make birds grow bigger and faster, but that they also might be contributing to antimicrobial resistance in both animals and humans. Whatever their efficiency benefits, the costs to public health could be greater, they claim, so using antibiotics solely for this purpose is unsustainable.

To address these concerns, the US Food and Drug Administration introduced new guidelines in December to limit the use of "medically important" antimicrobials — that is, antibiotics and synthetic therapeutics that are critical to human medicine — to the treatment, control and prevention of specific diseases in food animals.

"Therapeutic use of antibiotics in both human and veterinary medicine is the biggest driver of medically important antibiotic resistance, as is the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in countries that lack any regulatory oversight." DOUGLAS CALL, PHD

Over the next 3 years, feed and water medications containing medically important antibiotics will lose their performance claims and will be available only with a veterinarian's prescription and oversight. (Antibiotics with approved claims for improved weight gain and feed efficiency that the FDA does not deem medically important can still be used for this purpose under the new guidelines.)

According to Douglas Call, PhD, a professor of molecular epidemiology at Washington State University's Paul G. Allan School of Animal Health, the FDA's new guidelines could be beneficial in the face of rising antimicrobial resistance, although he observes that there is scant evidence linking animal antibiotic use to resistant human infection.

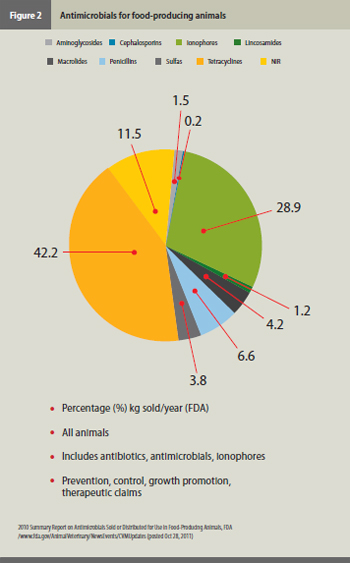

In an opinion piece he published in The Seattle Times last January, Call reports that farm animals are reliably linked to only three of 17 microbes that cause most resistant infections, according to the Centers for Disease Control, and 7.5% of related deaths.5 Furthermore, about 28% of feed antibiotics are ionophores, which are never used in human medicine. Another 42% are tetracyclines, which are used in humans only rarely.

It remains to be seen whether the new FDA guidelines will benefit public health. But according to Call, one thing is certain: Due to increased veterinary costs and loss of production gains attributed to antibiotics, food prices will rise.

"Rural producers with limited access to veterinarians would need assistance to cope, while small producers may be squeezed out of the market," he writes.

"If prices increase enough, consumers could favor cheaper imported foods for which we have limited regulatory oversight. This would also result in job losses for the US."

Preventing disease

Still, Call believes that even for medically important antibiotics, the public's preoccupation with "growth promotion" is overshadowing an opportunity to curb a greater and more established threat to both animal and human health.

"Using antibiotics to promote growth is probably not a major threat to public health," he writes. "Therapeutic use of antibiotics in both human and veterinary medicine is the biggest driver of medically important antibiotic resistance, as is the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in countries that lack any regulatory oversight."

According to Call, antibiotics with performance claims may work by preventing disease, thereby limiting the need for higher therapeutic doses. In an interview with Poultry Health Today, he pointed to evidence of this possibility in Denmark, which banned non-therapeutic antibiotic use in food animals in 2000.

Between 1999 and 2012, however, therapeutic antibiotic consumption by food animals rose by 86%, according to a Danish government report.6

"This increase in demand for therapeutic antibiotics substantially exceeds the growth of food-animal production over the same time period," Call observes. "Thus, we must ask: Did the disproportionate demand for therapeutic uses result from the loss of disease prevention afforded by low-dose growth promotion?"

In conclusion, Call suggests greater investment into alternative disease-control strategies that could limit the need for antibiotics in both human and animal medicine. For the time being, though, he believes that properly using antibiotics to enhance performance likely reduces demand for therapeutic doses. For this reason, he says, they generally do more good than harm — by protecting human and animal health, and also by assuring a safe, efficient and affordable food supply.

Conventional vs. alternative

To recap, proponents of conventional systems argue that antibiotics are important to sustainable poultry production primarily because they prevent and control disease. This results in better health and growth, and consequently, better animal and human welfare, greater economic and environmental efficiency, and a safe, abundant and affordable food supply.

In response to these claims, critics argue that "crowded" and "unsanitary" confinement systems are what invite disease and make routine antibiotic use necessary in the first place. With lower flock densities, greater outdoor access and better husbandry, they claim, the need for antibiotics could be significantly reduced or eliminated altogether.

Billy M. Hargis, DVM, PhD, a poultry science professor at University of Arkansas, does not doubt the possibility of raising healthy poultry without antibiotics; he even believes such systems will become more common over time.

The Great Outdoors

As the university's Tyson Endowed Chair for Sustainable Poultry Health, Hargis focuses on developing new health-management strategies, including sustainable alternatives to feed antibiotics. Some of these alternatives are proving highly effective — notably vaccines and some probiotics, he says. But of all the promising alternative solutions that have caught his attention, simply subtracting antibiotics and giving birds more access to the great outdoors currently isn't one of them.

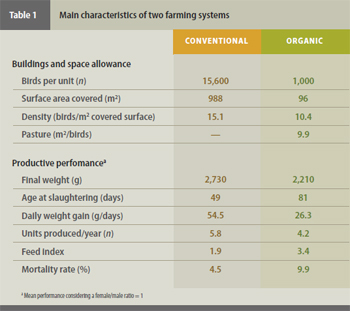

To make his point, Hargis refers to a 2006 study comparing conventional and organic poultry production, which by legal definition are free-range birds raised without antibiotics. (See sidebar on page 10 for more definitions.) Although the study was conducted in Italy, it is relevant to larger markets and widely cited throughout the US (Table 1).

Worth noting is that the study concludes that organic systems are more sustainable based on calculations of what's called "emergy" — a complex method of measuring all the direct and indirect energy required to make a product or sustain a system.

"Emergy is one way of looking at sustainability, albeit a rather abstract one, based on principles of thermodynamics," Hargis says. "I could argue with the calculations. But when I look at these data from a poultry health standpoint, I see a different picture — and you don't need to be a physicist to understand it.

notice that the organic systems had more than twice the mortalities of the conventional systems (9.9% vs. 4.5%).

Billy M. Hargris, DVM, PHD

"First of all," he continues, "notice that the organic systems had more than twice the mortalities of the conventional systems (9.9% vs. 4.5%). From this, we can infer that sickness and morbidities were also double," he says.

The study's authors directly attributed the higher mortalities to the fact that no antibiotics were used. But according to Hargis, the birds' free-range environment also could have been a factor, as it is more difficult to control pathogens — particularly parasitic diseases — in outdoor settings.

This conundrum presents a major issue for both animal and human welfare, he says. Even if organic production were to improve mortality rates, its relative inefficiency would still pose significant hurdles to sustainability and meeting the world's increasing demand for poultry.

"In the organic, free-range system, it takes nearly twice as long, twice as much grain and significantly more land to raise birds to an even lower bodyweight," Hargis says. "This means that we would need to havetwice as many poultry farms to make the same amount of chicken in the US - and that would mean less land for row crops

"Factor in the extra labor, energy and water needed and waste generated over the longer growing cycle, and we're talking about a very large environmental footprint — one that, on a large scale, would be incompatible with the needs of a growing and hungry population."

Wake-up Call

From ethical, economic and environmental standpoints, then, it appears that alternative production systems aren't necessarily as sustainable as many consumers believe they are. At a time when the industry is being called on to produce more with less, these alternative systems typically produce less with more — with few clear health or welfare benefits for either animals or humans.

The flip side of this is that conventional poultry production is actually more sustainable than many consumers think. For this reason, FACTA's Shepard says the industry should see the public's growing interest in sustainable food production not just as a challenge but also as an opportunity — to showcase what it is already doing to promote sustainability, as well as to explore ways of doing this even better in the future.

"The poultry industry is generally doing a fantastic job with welfare and sustainability and should be proud of the high standards it has achieved," he says. "Conventional producers need to help the public understand how their health and husbandry practices promote these standards, while assuring the safety, security and efficiency of their food."

Room for improvement

Proud as conventional producers should be, Shepard says, this does not mean that they should rest in their laurels, nor should they consider their health programs "sustainable," in absolute terms, just because of their advantages over alternative systems.

"There are many different definitions of sustainability, and consumers should be able to buy poultry according to their individual values and beliefs — all systems can be sustainable," Shepard says. "However, both conventional and alternative systems have much progress to make, and the health of their flocks will be key to making it.

"Is this a challenge? Absolutely," he continues. "But within it lies another opportunity to make a big difference — for poultry, producers, people and the planet."

More Issues