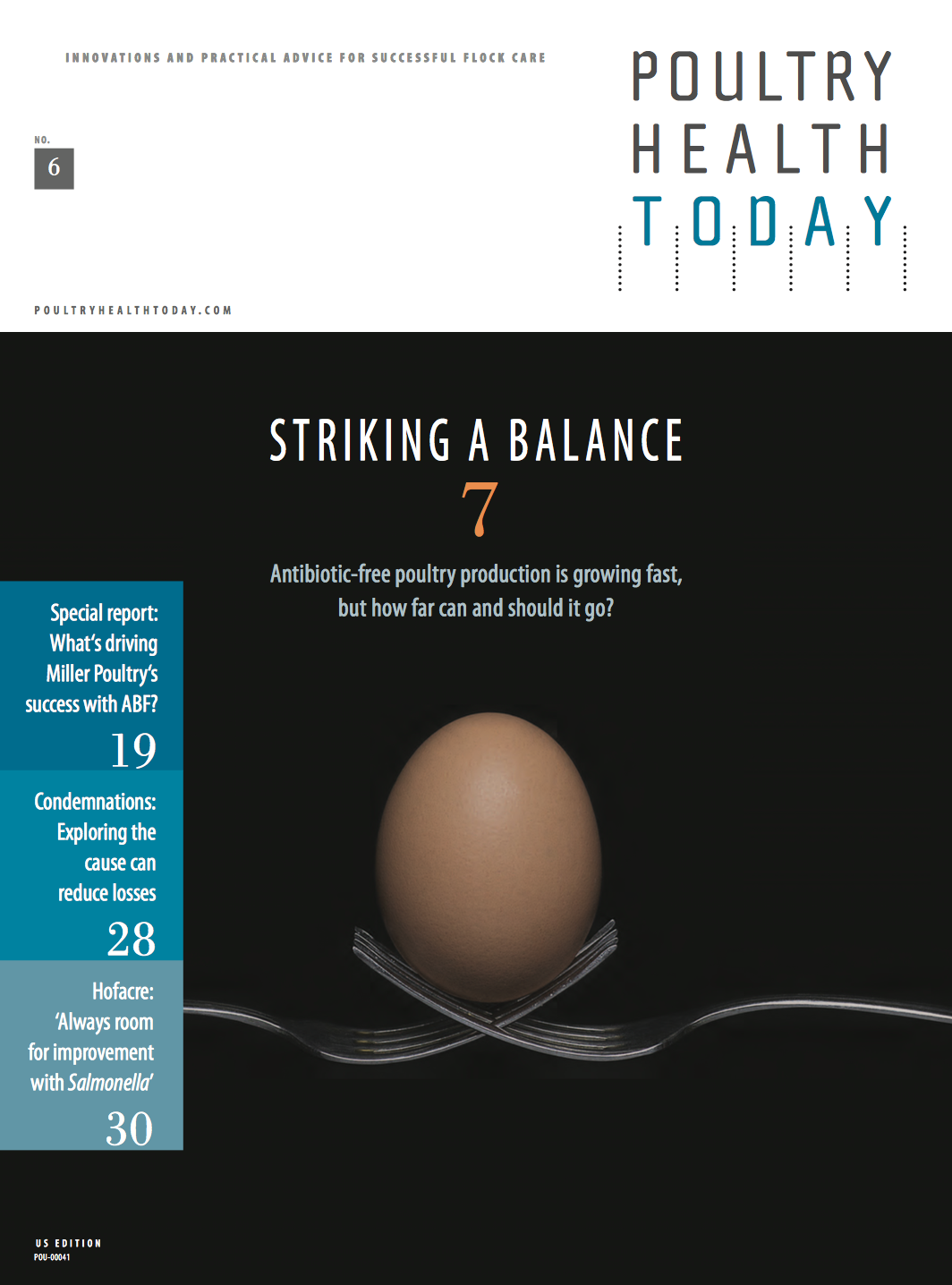

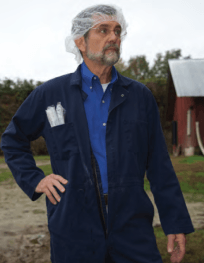

The Poultry Smith

After 40 years of practicing medicine, Fieldale Farms veterinarian John Smith has hung up his rubber boots and coveralls. Well, almost. In this exclusive interview with Poultry Health Today editor Joseph Feeks, Smith reflects on his career, the state of the US poultry industry and, most importantly, what it needs to do to ensure a healthier, more sustainable future.

Breaking into poultry

PHT: John Lennon once wrote, “Life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans.” Does that describe your career in poultry medicine? Or was this something you always wanted to do?

JS: I’d say John Lennon was right on the money. When I went to vet school, I never dreamed about being a chicken doctor. I had a previous career in ruminant medicine, in academia, specifically at Colorado State University. But after I got tenured and promoted, I decided I needed a change. I was from Georgia, the leading broiler state, and poultry looked like an interesting business — something that would give me more control over my time and my lifestyle and perhaps not be as hard on my body.

PHT: How is it less physical?

JS: Well, with poultry, there’s not as much emergency duty — nothing like pulling a calf in a ditch in the middle of the night. So mid-career, I went back and got my MAM (master’s of avian medicine) and moved back to Georgia. I’ve been in the field ever since.

PHT: So, other than those 2 a.m. emergency calls and the size and weight of your new patients, what other notable differences did you find between poultry and bovine medicine?

JS: With bovine, I was teaching individual animal medicine, which all veterinarians need to understand. You need to know how to examine an animal and diagnose a condition and how to treat it.

Poultry, on the other hand, is more population-based, though I think all phases of food-animal medicine are starting to follow the poultry model more and more. That individual approach still has a lot of importance and it’s certainly essential with some species or on some small farms, but it’s become less feasible economically in large-scale food-animal medicine.

PHT: At least with poultry, there’s more consistency in terms of genetics, the way birds are raised, the type of housing and even where they’re situated geographically. Does that make poultry medicine a little easier than caring for other livestock?

JS: Yes, I think it does. We’ve got fewer diseases to focus on and, as you noted, I’m dealing with the same breeds as my competitors. From that standpoint, poultry veterinarians as well as the research community can focus their limited resources on the big problems. That’s a big advantage. But let me assure you, it cuts both ways.

PHT: Can you give an example?

JS: One situation that comes to mind is the Avian Leukosis J-virus. That bug emerged and suddenly everybody in the industry had it. It gave us a lot of opportunity to collaborate and solve the problem, which we did. But on the other hand, the virus affected an entire industry — certainly North America and, I guess, the world — because of the limited number of breeders and how interrelated everything was.

A much more recent example was this new variant reovirus that appeared. All of a sudden everyone had it. That let us focus on it and find solutions. But reovirus affected a lot of businesses and a lot of chickens before we got a handle on it.

PHT: It sounds like you have no regrets about making the jump to poultry medicine.

JS: No regrets whatsoever. Population medicine has not been without difficulties and issues, but you use your head a lot more and your back a bit less.

We also have lots of data in the poultry business, so you can see the impact of what you’ve done, good or bad. You can also make adjustments and measure the impact. To be able to see that, measure it and know you contributed to the health of those birds is very gratifying.

JS: It’s hard to name just one, but I was involved simultaneously with Dr. Birch McMurray at Seaboard Farms back in the early ‘90s, identifying the Arkansas bronchitis that had moved into Georgia. The vaccine for it wasn’t permitted in Georgia, so we demonstrated to the state vet that it was here. He approved the vaccine and it was the most amazing turnaround I’d ever seen in flock health. It was like we threw a switch.

More recently, I’d say battling the Georgia 08 variant of IB. At Fieldale Farms, we built our own lab, made the vaccine, watched it work and then saw it get picked up by a commercial company so it could solve problems — not only for our company but for others. Infectious bronchitis has caused me a lot of grief, but I’ve also had some of my better moments with that disease.

PHT: Looking back, what has been your most gratifying experience in poultry medicine?

JS: It’s hard to name just one, but I was involved simultaneously with Dr. Birch McMurray at Seaboard Farms back in the early ‘90s, identifying the Arkansas bronchitis that had moved into Georgia. The vaccine for it wasn’t permitted in Georgia, so we demonstrated to the state vet that it was here. He approved the vaccine and it was the most amazing turnaround I’d ever seen in flock health. It was like we threw a switch.

More recently, I’d say battling the Georgia 08 variant of IB. At Fieldale Farms, we built our own lab, made the vaccine, watched it work and then saw it get picked up by a commercial company so it could solve problems — not only for our company but for others. Infectious bronchitis has caused me a lot of grief, but I’ve also had some of my better moments with that disease.

The war on disease

PHT: Let’s talk more about specific poultry diseases. Avian influenza is grabbing all the headlines these days — and for good reason. But is that really the biggest problem facing the broiler industry right now? Or are there other health problems that demand just as much, if not more, attention?

JS: That’s a good question. The USDA has said avian flu was the biggest animal-health emergency that’s ever occurred in this country, so we can’t discount that. This virus is different, and it’s now in our wild-bird population. The prediction is that we’re going to be living with it for a while, so it’s been a rule-changing event.

So, yes, I’d have to say flu is the biggest concern. But on the other hand, it’s probably diverted attention from other ongoing health issues we face.

PHT: And what would those be?

JS: The biggest economic issue and the biggest ever-present disease threat we’ve got is coccidiosis and gut health. And ironically, that’s where we now have this interesting collision of science and public opinion and politics — specifically, what’s happening to our drug availability to manage these diseases. To me, it’s creating a real crisis — another rule-changing event that ranks right up there behind flu as an issue that’s going to impact this industry.

And, of course, infectious bronchitis keeps rearing its ugly head. Here I am, cranking up our lab again to make another autogenous vaccine for a new IB variant.

Ground zero for IB

PHT: I’ve heard several poultry veterinarians say that Fieldale Farms tends to be ground zero for any new IB variants. Why does it have that reputation?

JS: I guess because it’s true. We’ve debated that internally. I’ve examined it myself and said, “What am I doing wrong?” My broiler manager says, “You look harder than other people.”

PHT: Is that a reasonable explanation?

JS: I can’t say what others do. All I know is that Northeast Georgia is a very poultry-dense area. I don’t know about houses or head per square mile, if we’ve reached the density of the Delmarva Peninsula — probably not — but there’s a huge number of chickens produced here.

This corona virus, which causes IB, makes mistakes when it replicates itself — and it doesn’t proofread those mistakes very well. Most of those mistakes are probably not advantageous to the virus and they disappear. But if you just look at the sheer numbers of IB viruses that are being replicated in this population — Connecticut, Massachusetts, Arkansas, Georgia 98, 072, 08 — we’re pouring all these viruses into these millions and millions of chickens, and they’re being replicated. Just consider the numerical odds that something new is going to emerge and take off. The vaccine lab we built at Fieldale is emblematic of the struggles we’ve had with IB. We use a lot of vaccines.

PHT: Other than bird density, are there other factors contributing to the high challenge of IB?

JS: I think so. Maybe it’s because we’re antibiotic free. We’re also smaller than many of our competitors, so I’m here almost all the time and I can drill deeper because I don’t have as many chickens to look over.

PHT: When we visited one of your growers, you examined some dead chicks and said they had signs of E. coli infection. Traditionally, that hasn’t been a problem in broilers. Are you seeing more E. coli these days?

JS: E. coli is a very common secondary invader that complicates any number of conditions, whether it be chick quality issues or IB. We’re not seeing more of it now, but we started seeing more of it when we took gentamicin out of the Marek’s vaccine. And in my opinion, that needed to be done. That was not a defensible or judicious use of a powerful antibiotic. Without the antibiotic in the vaccine, it shows up your warts a little bit more, and we see some other infections. You need to depend more on vaccination and good management.

Lessons from avian flu

PHT: Let’s get back to avian flu. So far in the US, significant economic losses to avian flu have been limited to the layer industry and turkeys. What lessons have emerged from this experience? Have there been any silver linings in the avian flu cloud?

JS: Definitely. Avian flu underscored the need for greater biosecurity. It allowed me to sell a bunch of biosecurity procedures to our contract growers — ones they might have resisted in the past but procedures we should have been doing all along. The flu instilled enough fear in people that people bought in pretty readily. Like everyone else, we now have a lot of enhanced procedures in place that I’m hoping will benefit us with some of the other things we deal with, like bronchitis and mycoplasma.

PHT: What are the most significant changes you implemented with your growers?

JS: We developed this idea that the threat is not off the farm but right outside the door of the chicken house. And so the inside of that chicken house needs to be “the green zone” or “the clean zone.” Anything that goes in there needs to be clean and disinfected.

Over the past year, we’ve really beefed up our procedures with footbaths. We’ve got deep buckets now with brushes. We’re using what we think is a little bit more expensive but a better quality disinfectant. We’ve actually put physical lines on the floor that serve as a visual reminder that anything that crosses this line needs to be clean and disinfected. When you come back from town, you need to protect your chickens — disinfect your truck’s tires, change your clothes, wash your hands and have dedicated clothing and footwear. So it’s brought about a change in overall attitude.

PHT: That must have been a difficult change to instill in today’s work culture, where so many people are programmed to multi-task, get as much done as they can and not focus on any one thing.

JS: Yes, and that has been difficult. But the intense fear over the flu, which is justified, got it done. That was the difference. Biosecurity requires more time and it’s a hassle, but something had to give. The cost of not complying is too high.

Environmental factors

PHT: When you look at all the diseases that threaten broilers, what is the one factor that, more than anything, determines flock health and overall well-being?

JS: That’s a difficult question, but my first reaction is the birds’ environment. You know, if you look at it year after year, we usually do great in September and October, and then life becomes very difficult for us in February, March, April. And it’s always the environment — it’s the management of the birds and the houses.

PHT: But even in those off months, it seems today’s birds are still remarkably resilient and efficient. Production numbers are fairly constant.

JS: And they are. Generally speaking, when you look at the productivity of these birds today, it’s absolutely amazing. Most of that has been genetics, but management, house design, equipment design, certainly veterinary care and scientific nutrition, have all contributed. We’re putting out more pounds per square foot per day than ever, and the livability gets better and the condemnations lower. But even so, there’s still a tremendous amount of stress on the birds. We need to do a better job managing their environment.

PHT: Now, are you referring to the management of the birds on individual farms or are you talking about the US poultry industry as a whole?

JS: Well, both. Our industry has developed what some people call mega-farms — places like Northeast Georgia and Northwest Arkansas, with lots of different companies, managers and too many birds crammed into one region that are being turned too quickly. We could resolve a lot of disease issues if we could somehow ameliorate that.

The problem is economics. There’s a huge amount of infrastructure that’s been built, much of it with private contract growers. How do you disperse that without a bunch of people getting hurt economically? It’s a tough question.

PHT: How much of a factor is litter management? In Europe and Canada, they change it after every cycle. In the US, most producers use built-up litter for a year or more. Does that affect the health of birds?

JS: Yes, but not in the way you might think. In fact, from the standpoint of managing immunity and gut health, there are lots of advantages to reusing litter beyond the obvious economic and environmental advantages. Some of the worst coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis you’ll see is in birds on new litter.

Now, if a customer demands that we clean that house out more frequently than we’d like in order to meet certain production specifications, we can do that, but they’ll be more susceptible to enteric disease. That, in turn, increases the need for treatment. There are always tradeoffs.

Antibiotic-free production

PHT: One big tradeoff is antibiotics. Fieldale Farms has had an antibiotic-free program for over 15 years, and has been almost totally antibiotic-free in recent years. Many other poultry companies are now experimenting with antibiotic-free production. Is this a good direction for the industry?

JS: You know, looking back, I think there are times when maybe this industry might have over-treated birds or was quick to pull the trigger on a disease. But today, with the pressures we’re under to reduce or eliminate antibiotics, the pendulum is swinging the other way. If we’re not careful, if we let it swing too far, that can negatively impact animal welfare in some situations. The industry needs a balanced approach; we can produce poultry without antibiotics for a portion of the market. But birds will get sick and if you send sick birds to slaughter that should have been treated, there’s greater potential for more carcass contaminations and potentially more pathogen contamination in that flock. We need to find a balance.

PHT: Opponents of using antibiotics in poultry have long maintained that if these birds were not raised in what they perceive to be crowded, unsanitary conditions, they wouldn’t have a lot of these health issues in the first place and, therefore, would not need as many antibiotics. Do you agree with that argument?

JS: I obviously hesitate to say this, but unfortunately, I do, for the most part. I think that we could take care of a lot of health problems if we could spread out the birds — not just geographically, but also spread them out more in the house and give them more time between flocks. Again, the problem is economics; who will pay for it?

I’m not suggesting we abandon the integrated system, nor do I think we should abandon closed houses with tunnel ventilation and computer controls; those are great. It’s the economics — and we’ve pushed them to the breaking point.

PHT: So, do you think lowering bird density is doable with the industry’s current model?

JS: I’ve looked at it. We had a few houses that, because of a contract with a certain customer, we placed at a very loose density. Those birds performed phenomenally well. But to keep the contract grower profitable, to keep his yearly income intact, the extra pay that we had to give him totally wiped out the economic advantage in reduced health costs, so it was a wash.

The point is that we could, as in industry, reduce bird density and antibiotic usage. But to do it all the time, in all flocks, we’d have to expand our operations about 20% — more square footage, more houses, more miles down the road with feed trucks.

So again, it’s another example of pushing the poultry industry to the economic edge. The only way to fix it, short of government fiat, is getting consumers to pay for it — and I mean all of them, not just an elite few. And they’re going to have to want it badly enough to pay more for a pound of chicken so more companies can go antibiotic free and have a density of 1.25 feet of space per bird. Unfortunately, the general public has no grasp of the consequences.

PHT: You’ve understandably had some ups and downs with 100% antibiotic-free production, but overall it appears to have been a success. Based on your experience, is it economically feasible for the entire US poultry industry to one day raise all broilers without antibiotics?

JS: No, I don’t believe so. These groups that want to ban all antibiotics — they’re throwing out the baby with the bath water. A lot of the antibiotics used by the poultry industry are entirely harmless to human medicine, and they provide tremendous benefits to bird health and welfare, to the efficiency of production, and therefore to society. Ionophores, bacitracin and, in my opinion, virginiamycin — we shouldn’t abandon those, particularly until we’ve got some other solutions. But we’re living in an age of sound bites; people don’t understand the complexity of the issue, so they won’t listen.

Meeting customers’ needs

PHT: Let’s stop a moment and think about a few old but sound business expressions — “keep the customer satisfied” and “give the customers what they want.” Right or wrong, if customers are saying they don’t want antibiotics anymore, how should the poultry industry respond? Does it just forge ahead and pass on the cost to consumers?

JS: That’s clearly what some companies are doing, and, in some cases, they’re adding fuel to the fire by suggesting that one type of poultry is healthier or safer than another. Poultry has become a marketing arms race. What can I do to distinguish my product a little bit more than what the last guy did?

I also contend that going antibiotic-free on a large scale is going to increase the industry’s carbon footprint. If it takes more space, more feed, more time to raise these birds without modern technology, then you’re going to produce more manure, consume more corn and beans and take up more space.

PHT: So what’s the long-term solution? More consumer education?

JS: Some groups have made efforts to educate the public, but it’s a complex issue — one that is influenced by emotion and politics. Credibility is also an obstacle. The industry is the only group with an interest in defending the current system, but in the minds of some consumers, the poultry industry is the fox watching the henhouse. Some people also can’t grasp that poultry is a business and that we need to turn a profit in order to provide a consistent, safe and dependable supply of poultry meat. Yet the profit motive is nowadays often suspect, which is unfortunate.

I don’t know what the ultimate answer is, but I do know our industry is fueling the problem to a large extent.

PHT: Why, in your mind, has poultry become the lightning rod for all this? It doesn’t seem like activists are targeting beef or pork with the same ferocity.

JS: Well, beef has taken plenty of flak for things like E. coli O 157 in ground beef, but you’re right — it does seem that poultry bears the brunt of it. There are a number of potential reasons, one being that all of our treatments are mass-administered.

The Baytril (enrofloxacin) situation is a good example. We lost that drug for poultry but the beef guys still have it. It’s a fluroquinolone and acts the same in both environments, but FDA wasn’t comfortable with it being mass-administered, even for a short period, which is what we have to do in poultry. With beef cattle, it’s injected as needed, one animal at a time.

The other issue is that beef cattle and pork are skinned, whereas many of our products are whole birds or parts with skin on. There’s naturally more risk for contamination.

Then there’s the way our industry is structured and how we’re perceived to be big industrial agriculture.

PHT: No red barns, picket fences and rolling green pastures?

JS: Correct — and no little white farmhouses, either.

What most people don’t realize is that most chickens are still raised on family farms. As one of my colleagues used to say, this business has built a lot of nice little brick houses in Northeast Georgia on old, worn-out land. It also sent a lot of kids to college.

Think about it: Where else can someone who inherited 40 acres and maybe has a high school diploma go and borrow $1 million to start a business? Poultry is a business that, if you give it a reasonable effort, you’re not going to get rich, but you’re going to succeed. You’ll pay off that loan, that land and your house note. It’s not a glamorous business, but if you want to stay on the farm and keep your land and build a business on it, poultry is not a bad way to go.

Bacterial resistance

PHT: The US now has a three-tiered market for chicken — birds raised without antibiotics, birds raised without human antibiotics and traditionally raised birds that get FDA-approved antibiotics under veterinary supervision. Yet, the National Chicken Council and others have made the point that all chicken meat is still “antibiotic-free” by the time it gets to the meat case or restaurant.

JS: True, but playing devil’s advocate here, it’s not just the question of whether there are antibiotic residues in poultry meat. We know there aren’t any. They’re asking whether using antibiotics promotes resistance in the bacteria that might be on that meat.

PHT: Well, you’re a veterinarian with two master’s degrees — one in medical microbiology and bacteriology. What’s your view? Do resistant bacteria found on poultry carcasses present a risk to humans?

JS: Anything’s possible when you’re dealing with bacteria, but there’s a bunch of hurdles that have to be crossed for that to occur. First, that antibiotic-resistant bug has got to persist through processing on the meat — and some of it can. Second, it’s got to be a foodborne pathogen, which some of it might be. Third, the meat has to be mishandled or not cooked properly. Fourth, a resistant bacterium has got to make somebody sick enough to seek medical treatment. And if that happens, there’s got to be treatment failure for resistance to become an issue.

So while it’s important, I think this threat has been blown way out of proportion, and I think the response needs to be in proportion — and, at present, it is not.

Educating the public

PHT: Numerous marketing surveys have shown that veterinarians rank highly with consumers in terms of respect and trust. If veterinarians wield so much clout, could the veterinary profession be doing more to educate the public about antibiotics and their role in poultry medicine?

JS: Possibly we could, yes, but there’s still the credibility issue I mentioned earlier — at least in poultry. Most production veterinarians are employed by large poultry companies, so some might see that as a conflict.

In my opinion, the AVMA (American Veterinary Medical Association) has really tried to defend the veterinarian’s access to antibiotics and our ability to continue to treat animals, but perhaps we should be doing more.

PHT: It seems the AAAP (American Association of Avian Pathologists) has been relatively quiet defending antibiotics.

JS: Yes, I think we have. We have an antibiotics committee — and I’m on that committee — and we do try to respond to some of these issues that come up with, say, Louise Slaughter (D-NY) and other lawmakers. Our efforts are frequently retroactive. It often consists of a white paper or a letter that probably gets a little exposure. And often — as far as any impact on the general public — it is probably too technical.

So yes, I guess we don’t make a lot of noise at AAAP. But it’s a small outfit — it’s all volunteer and we all have jobs. Few if any of us are trained in PR. And then a lot of us are — you know, if you work for a production company like I do or you work for a pharmaceutical or vaccine company — you’re not just speaking for yourself. You have to be pretty careful about who you get in front of and what you say, because it often gets twisted. So I think there’s a lot of things that have inhibited us from taking a more active role and being a better voice.

Evaluating new products

PHT: Considering all your experience with antibiotic-free production, I imagine you get a lot of people knocking on your door, presenting data and telling you about their newest and greatest innovation for managing coccidiosis, necrotic enteritis and other diseases. How do you separate the contenders from the pretenders?

JS: You’re absolutely right. Because our farms are antibiotic free, we get called on an awful lot by sales reps and technical people asking if we’ll look at their product. I usually tell people I need to see data — pen trials and/or well-controlled field trials, which are difficult to come by. If there are convincing data there, that’ll get my interest. Then I need to test it in my environment, in my flocks.

PHT: Is it difficult to evaluate new products?

It certainly can be, but it depends on the type of product.

If it’s a new vaccine that’s applied in the hatchery, I can test that pretty easily — week on, week off for 8 or 10 weeks. Let those flocks go through the system, collect the data, see if I get a payback or measurable effect.

In-feed products are a lot harder, because the mill’s got to make two series of diets and deliver the right batch every time to the treated farm or the control farm. That’s the most reliable, efficient, controllable way to evaluate these antibiotic alternatives.

There are also water-soluble products, but frankly, giving them to the grower to put in the water is fraught with all kinds of variables, difficulties and inconsistencies. They’re very hard to evaluate.

Advising the next generation

PHT: What advice do you give to your younger colleagues or people who are perhaps in vet school thinking about becoming poultry veterinarians?

JS: I tell them there are advantages to the production side of the business — things you may not experience in private practice or academia. As I mentioned earlier, you’ve got a little more control over your time and your lifestyle, and it can be economically rewarding. But I also warn them about the negatives.

PHT: Such as?

The negative reactions they might get from their peers. Agriculture has been subject to a lot of criticism lately, particularly its industrial scale. Animal welfare is a concern. There’s also food safety, drug use and technology in general.

The veterinary students today are mostly urban and companion animal-oriented, so I think a lot of them don’t understand fully what we do and how we do it; some even think we’re evil. And so I warn these young people about what they’re going to face from their colleagues in the profession and the public in general.

It’s a challenging environment but a rewarding one, too.

Moving forward

PHT: What, in your mind, does the US poultry industry do really well?

JS: We’re an incredibly efficient producer of high-quality protein for a growing hungry world. Poultry is really coming to the forefront with the consumer, with advocates for a healthy diet, to the extent that they approve of eating meat. So, I think we’ve done a very good job at what we were asked to do post-World War II: produce plentiful, inexpensive, wholesome, nutritious meat.

PHT: What are the poultry industry’s biggest areas for improvement?

JS: We’ve got some ways to go with food safety. We can’t say “just cook it” anymore. You know, we’re selling a food product that has stuff in it that can make you sick if companies and consumers don’t take the right precautions. We have a good safety record as an industry, but I think we need to stay after that.

Welfare is going to be an increasing issue — and probably should be. There are certain areas — catching and hauling and slaughtering, for example — where we could improve without insurmountable investments.

Speaking personally

PHT: As of 2016, are you making a clean break from poultry or will you still be involved in the industry?

JS: I will still be involved, giving 25% of my time to Fieldale. I’m going to keep my licenses up so I’ll try to go to a couple of meetings a year. I might agree to give some talks.

PHT: And when you’re not involved with chickens, what do you anticipate doing with your free time?

JS: I want to get more into gardening with my wife, Emily. I also want to revive my bee-keeping hobby, which has suffered. It’s gotten harder to keep bees. Foreign pests have come in over the last 20, 30, 40 years. Tracheal mites, Varroa mites, viral diseases, forage loss, and pesticide use have all made beekeeping much more difficult.

PHT: That sounds an awful lot like poultry. Is there anything you’ve learned from poultry that ‘ll make you a better beekeeper?

JJS: Yes, and I think I may be seeing an impact. As with broilers, it’s all about density and biosecurity.

PHT: Any chance of adding a few backyard chickens?

JS: I’d like to, but not as long as I’m still working with Fieldale. That’s a rule I made for our employees, so I have to live by it, too.

PHT: All modesty aside, John, what would you say was your biggest contribution to poultry medicine over the last 25 years? Is there something in particular you want to be remembered for?

JS: Let’s be perfectly honest. We’re in a business and I don’t expect to be remembered — and that doesn’t bother me. I try to give an honest day’s work for my pay, and I’ve always tried to do the best I could. I guess I’d like to be remembered for that.

More Issues