Waves of Progress  BROUS SARD: Spray it onThe results of a recent study indicate

that the method used to vaccinate

chickens for coccidiosis can have a

significant impact on the percentage

of them that are successfully protected.

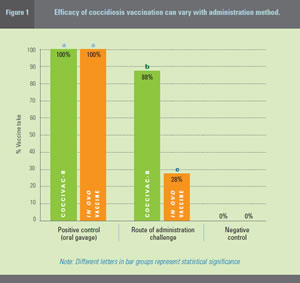

A coccidiosis vaccine sprayed on at 1 day of age yielded a vaccine take that was 60% higher compared to an in ovo coccidiosis vaccine, said Dr. Charlie Broussard, director of US technical services for Intervet/Schering-Plough Animal Health. The initial part of the study was conducted at a commercial hatchery in Maryland. Broiler chicks received Coccivac-B with a SprayCox II unit at 1 day of age, or an in ovo coccidiosis vaccine was administered to 19-dayold embryonated chicken eggs. Both vaccines contain live coccidial oocysts. The study also included three controls. One control group received no coccidiosis vaccine. The other two received an oral gavage of either Coccivac-B or the in ovo vaccine to demonstrate the effectiveness of both vaccines when a sure-fire method of administration is used. After vaccination of birds that received Coccivac-B and after hatch of the in ovo group, birds in each group were independently segregated to ensure they were not infected with oocysts from hatch-mates, he said. Investigators measured first-cycle output to determine the effectiveness of the vaccine-administration methods. For this part of the study, they individually numbered and tagged the birds before moving them to segregated units at the University of Delaware’s Lasher Lab, where Drs. Dan Batista and Miguel Ruano microscopically analyzed feces. “If one or more coccidial oocysts could be identified on any day of the trial period, which was 5 to 8 days post-hatch, then the bird had a positive vaccine take,” Broussard said in an interview after the meeting. The group sprayed with Coccivac-B on the day of hatch had a vaccine take of 88%, compared to 28% in birds that received the in ovo vaccine, he said (Figure 1).  As expected, vaccine take was 100% in birds that received either Coccivac-B or the in ovo vaccine by oral gavage. None of the unvaccinated control birds shed oocysts. Why was vaccine take so much better for spray vaccination than in ovo administration? “In ovo administration of a coccidiosis vaccine is a lot more difficult,” Broussard said. With in ovo coccidiosis vaccines, live coccidial oocysts need to get to a certain area in the egg where they can be swallowed, then move to the gut, where they infect intestinal epithelial cells and initiate immunity. In addition, unhatched birds don’t have digestive enzymes at work to break up and aid the digestion of oocysts releasing the infective sporozoites, he explained. “With other types of vaccines, such as viral vaccines, it doesn’t matter whether you give them in ovo, subcutaneously or intramuscularly — you achieve your goal. The margin of success is just a lot better than it is when compared to a coccidiosis vaccine,” he said.  PUTNAM: ‘Living on the edge’ with coccidiosis control

“If you don’t think immunity, you are living on the edge” when it comes to coccidiosis control, said Dr. Marshall Putnam, director of health for Wayne Farms, LLC, Oakwood, Georgia. Immune-system status is the foundation for any successful coccidiosis-control program, he emphasized. Putnam cited a study demonstrating that driving oocyst leakage and coccidial cycling late into the production cycle costs money because it’s a time when birds grow and eat the most. In addition, late coccidial cycling can leave the house overburdened with coccidial oocysts, which can be too much for the next flock. Instead, “we want to promote [oocyst] leakage up front,” when coccidial cycling has the least impact and enables birds to develop immunity early in life, he said. One way to achieve early cycling is with coccidiosis vaccination because “you’re done with oocyst cycling by 28 days of age,” the veterinarian said. The goal at Wayne Farms, which rotates a coccidiosis vaccine with anticoccidials, is to maintain consistent bird performance, flock after flock, regardless of which coccidiosiscontrol method is used. “No change in performance means we’re managing well,” he added. Putnam advised against making changes in the coccidiosis-control program based on minor fluctuations in performance that might occur over a week or two. “I like to look at a whole year and from year to year, not week by week,” he said. This approach can help identify other factors that affect coccidiosis control such as house conditions, litter moisture, old versus new litter, bird density and the immune-system status of the birds. To get the best results, it’s also imperative that the poultry company’s live-production staff is “on board” with whatever coccidiosis-control program is implemented, he said. Putnam recommends posting sessions to measure the effectiveness of coccidiosis-control programs.  HOFACRE: Coccidiosis called ‘primary trigger’ for NE

Coccidiosis is a “primary trigger” for necrotic enteritis, a costly but sometimes undetected gut disease that is a risk with any anticoccidial program that allows coccidial oocyst cycling, said Dr. Charles Hofacre of the Poultry Diagnostic and Research Center, University of Georgia, Athens. Virtually all poultry farms have coccidiosis and coccidial cycling — the reproduction of coccidial oocysts — which cause damage to the intestinal cells, leading to mucus production and disrupting the balance of bacteria in the gut, he said. Mucus is a food source for Clostridium perfringens, the organism that causes necrotic enteritis (NE). ROLE OF ALPHA-TOXIN Not all types of C. perfringens produce the alpha-toxin that leads to NE, but the ones that do cause more gut damage as they proliferate, which leads to more mucus and more C. perfringens, he said. Antibiotics and anticoccidials control C. perfringens and prevent NE, but with the pressure on to use fewer drugs in food animals, producers are searching for other methods of controlling NE. One way is to maintain a healthy balance of bacteria in the gut to prevent clostridia from gaining a foothold. This may be accomplished by using coccidiosis vaccines, C. perfringens toxoids and competitive exclusion products, Hofacre continued. Coccidiosis vaccines contain live oocysts that cycle and produce more oocysts. However, oocyst cycling after vaccination on the day of hatch allows birds to develop immunity to coccidiosis early in life, when the disease has less impact than it does later in the production cycle. Once vaccinated birds develop immunity to coccidia, they won’t have the major trigger for intestinal damage and will have a healthier gut, which makes them less susceptible to NE. “If properly administered,” Hofacre added, “coccidiosis vaccination should minimize NE.” PASSING ON IMMUNITY He pointed out that C. perfringens toxoids have been used successfully to control clostridia in several other food animals for many years. Asked about field experience with a C. perfringens toxoid that’s being commercially developed by Intervet/Schering-Plough Animal Health, he explained that the toxoid is administered to breeders, which pass on immunity against C. perfringens to broiler progeny. “I’ve not done challenge studies myself,” he responded, but “it does seem to work from the results of studies I have seen. It probably modulates the gut flora and keeps C. perfringens digestive enzyme toxins in check so that C. perfringens doesn’t colonize the young chicks’ intestines. It may well have a place in NE control.” Competitive exclusion products are another way to help maintain a healthy balance of gut bacteria. Other products being investigated for control of NE include organic and inorganic acids in water and feed, digestive enzymes, essential oils and herbal extracts, he said. MATHIS: Immunity development crucial for successful coccidiosis control  The development of immunity against coccidia is crucial for any successful coccidiosis-control program, said Dr. Greg Mathis, president of Southern Poultry Research, Inc., Athens, Georgia. “With each cycle of coccidia in the host, immunological protection increases,” he said. “The development of self-limiting immunity, which eventually protects a flock, is a very critical objective for a coccidiosis-control program, whether [it be] vaccination or an anticoccidialdrug program.” Anticoccidials are still successfully used to control coccidiosis in poultry, but numerous reports have demonstrated that coccidial oocysts are less sensitive to both ionophores and chemical anticoccidials. With ionophores, some coccidial parasites survive and stimulate immunity, while chemical anticoccidials permit only limited immunity development, said Mathis, a coccidiosis expert. SIGNIFICANT IMMUNITY Reduced coccidial sensitivity coupled with increased public demand for drug-free birds has led to increasing use of coccidiosis vaccines in the last few years, Mathis continued. With vaccines, a controlled dose of live coccidial oocysts is administered at an early age. Significant immunity develops by 14 days after vaccination, allowing birds to withstand a substantial coccidial challenge by 21 to 28 days of age. “Vaccination programs can equal effectiveness and performance” of anticoccidial-drug programs, he added. Vaccines are also used to restore the sensitivity of coccidia to anticoccidials by seeding the house with oocysts that are still sensitive, Mathis said. The Eimeria oocysts in Coccivac-B are not attenuated (altered to reduce their virulence) and are “very sensitive to anticoccidial drugs,” Mathis said. The vaccine’s oocysts are generally milder than field strains but maintain their reproductive and immune-stimulating characteristics. TESTING RECOMMENDED Mathis concluded that even though coccidiosis is ever-present on poultry farms, it can be controlled. When using in-feed medications, he recommended anticoccidial sensitivity testing to determine which ones, or if any, will be effective on a given farm. If vaccinating to control coccidiosis, he suggested paying close attention to proper vaccine storage, careful vaccine application and good farm management to achieve the best results. In response to a question about whether oocysts in coccidiosis vaccines could develop resistance to anticoccidials, Mathis and other speakers gave a resounding no. Coccivac-B, for example, was developed in the 1950s, well before anticoccidials were introduced. Oocysts in the vaccine have never been exposed to anticoccidials; each time the vaccine is used, sensitive oocysts are introduced into the poultry house. Back to North American Edition (#3) |