CME: Challenge of High Feed Costs

US - The debate over feed costs and availability took center stage last week at a hearing of held by the House Sub-Committee on Livestock, Dairy and Poultry, write Steve Meyer and Len Steiner.Representatives of all three sectors discussed the challenges of high feed costs and their concerns about whether sufficient feed would be available for US producers’ needs should a true short crop occur in the next few years.

And there is no doubt that the total supply of high-energy feed ingredients is declining.

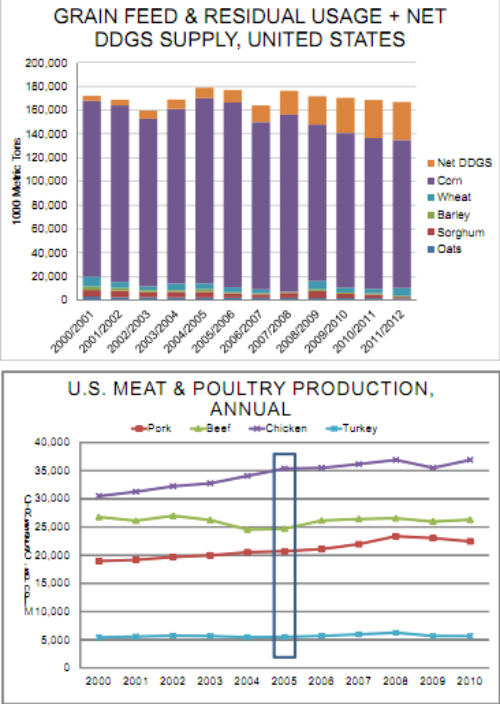

The chart below shows the amounts of corn, wheat, barley, grain sorghum, oats and distillers dried grains with solubles (DDGS) used as feed/residual for each crop year since 2000-2001 and projected for 2011-2012.

We interpret this as “feed availability” in that it is the amount used by livestock and poultry after food, seed and industrial (which includes ethanol) and export needs are met.

The amount of corn fed to animals in the US in 2011-2012 is projected to be 124.466 million metric tons, 20 pper cent less than in the peak year of 2004-2005. To be fair, we must add the DDGS produced in the ethanol refining process to that feed supply since it comes from the corn that is used for ethanol. But DDGS fills different purposes for different species.

DDGS contains 18-20 per cent protein but the protein is of relatively low quality. That is, it contains relatively low concentrations of the essential amino acids that must be present in pig and poultry diets since those species cannot effectively synthesize amino acids.

On the other hand, the protein in DDGS is great for cattle since the microbes in the cow’s rumen can make higher-quality protein from lowquality protein or even non-protein nitrogen. So, DDGS used in cattle diets is more of a protein supplement while it fulfills primarily an energy role in other diets and, since most of the corn kernel’s energy (ie. starch) is removed in the ethanol refining process, its usefulness is limited.

Poultry diets can generally only contain 10-20 per cent DDGS while swine diets can use, on average, 20-30 per cent DDGS with some phases containing as high as 40 per cent.

No one knows, though, exactly how much DDGS goes to which species so an accurate energy vs. protein accounting for DDGS is impossible.

Here we are giving DDGS full credit as an energy source for livestock feeds. That is an overstatement to be sure but one that provides a conservative view of the decline in highenergy feed availability. Total corn plus DDGS availability for feed peaked in 2007-2008 at 176.267 million tons.

The projected 2011- 2012 figure of 166.804 million metric tons is down 7.4 per cent from ‘07-08. Projected 2011-2012 feed availabilities of all other grains except wheat are significantly lower than in 2004-2005.

Oats are down 30 per cent, sorghum is 71 per cent lower and barley is 61 per cent lower than that year. And all three are sharply lower than last year as well.

Wheat feed availability is projected to grow significantly (87 per cent) this year and to be about one-third higher than in 2004-2005. The amount of wheat available for feed has historically been quite variable since it must be in abundant supply to be cheap enough to substitute for corn.

Higher corn prices will obviously make this happen more often so this year’s trend toward higher wheat feeding will likely continue provided world wheat supplies remain strong.

US livestock and poultry producers have, so far, handled lower feed availability by becoming more efficient. In fact, the outputs of all four major species have grown even while feed supplies have dwindled.

Compared to 2005, US output of beef, pork, chicken and turkey have grown by 6.6, 8.5 , 4.4 and 2.5 per cent, respectively.

The questions are “How long can these efficiency gains continue?” and “What happens when a truly short crop comes along?”