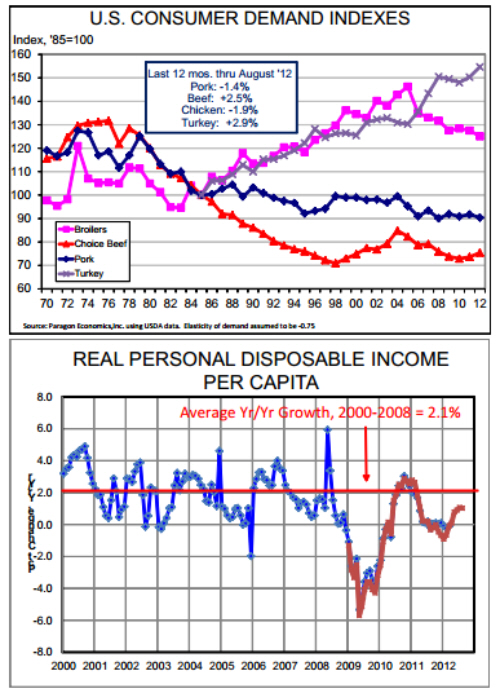

CME: Major Protein Demand Indices Mixed

US - Last week’s release of monthly export data for August provided the last needed piece to compute demand indices and the results continue to be mixed for the four major animal protein species, write Steve Meyer and Len Steiner.Annual indexes with 1985 being the base year (index = 100)

appear below. The last observation represents the 12 month period

ended in August versus the same 12 month period one year earlier.

Pork and chicken demand remain lower than one year ago while beef

and turkey demand remain stronger through August.

The challenge for pork demand has been lagging per capita

disappearance/consumption. This key figure was 2% lower for the

September-August period. As readers well know, lower consumption

does not mean lower demand — unless it goes with price changes

that are smaller than expected. That 2% drop in consumption should

be associated with a relatively robust price increase but the actual

deflated retail pork price was only 0.8% higher, on average, during the

period. Chicken’s challenge was similar but we would argue that the

disappointment here lies in the prices that have resulted from significant reductions in output. The real price of chicken rose only 2% versus the same 12 month period one year earlier while per cap disappearance/consumption was, on average, 3.4% lower. The price situation has been improving for chicken but a deep demand index hole

was dug early in the year.

Last week we made what we think is a very clear case that

the U.S. livestock and poultry sectors have much at stake in world

economic issues. But they have much at stake here at home as well.

While expenditures for food in general and meat in particular comprise a

very small percentage of U.S. consumers’ average expenditures, the

shares are rising and the means for making those expenditures continue to flounder amid the slow recovery from the Great Recession.

Most notable, we think, among the macro variables that influence consumer demand for all goods and, since meat is a relatively

expensive component of food expenditures, meat in particular is real

disposable income per capita. This variable measures the total amount

of money each consumer has after taxes and inflation have been removed. It is, in essence, take home pay with its purchasing power held

constant. And, as can be seen at right, it has not fared well since 2007.

Real disposable income per capita growth averaged just over

2% from January 2000 through 2008. That period includes the beginnings of the economic slowdown in 2007 but also included the 5.9% yr/

yr spike of May 2008 which was driven by federal tax rebates. The

growth rate of per cap disposable income, of course, got worse in 2009

before actually turning positive in mid-2010. But those 2 to 3% rates of

late 2010 and early 2011 are primarily due to the dismally low values of

per cap disposable income in 2009 and 2010 and the growth rate has

been nothing to shout about since then, averaging –0.2% from May

2011 through April 2012. It didn’t climb above 1% until July when it hit

the robust level of +1.1%, yr/yr. And August’s yr/yr increase was only

1% — a number which we would not call “encouraging.”

When consumers are receiving less money they will, even in

this credit-driven world, eventually spend less money. And real personal consumption expenditures (see chart on page 2) show just that. The

yr/yr growth of real consumption expenditures declined sharply during

the recession and then climbed back to pre-recession levels in late

2010. But after hanging near 3% for about 6 months they declined

steadily through the last 3 quarters of last year and have been basically

flat at about 2% this year.

And remember that these two charts are deflated using the

inflation rate for all goods — while prices for beef, pork, chicken and

turkey have risen at a much higher rate.

Why is per capita consumption of meat and poultry lower?

Because consumers cannot afford to buy as much meat and poultry at

prices that producers and processors now require in order to bring them

that much product. Short version: It’s costs, stupid.

Further ReadingYou can view the full report by clicking here. |