Knowing Your Onions: An Open Minded Approach to Broilers

UK – A former arable farmer has taken lessons learned from vegetable production and applied it to a broiler enterprise to monitor how contented his birds are. Michael Priestley reports.At the same time, David Speller of Applied Poultry has ensured consistent chicken size, which has allowed him to build a progressive business around the skeleton of a 1960’s broiler farm he bought in 2004.

By decking out his 180,000 bird Derbyshire poultry farm with extensive shed surveillance and monitoring equipment, David is able to react quickly to any production snags that arise.

Arable farming is heavily dependent on gadgets big and small and David says this may have helped him make big steps in the poultry sector.

“Computers are not only running my farm but also assisting in bird welfare monitoring on a daily basis, says David. “If there is a problem, we can get out and sort it quickly.

“Knowing that food conversion was a problem in a batch when they have been slaughtered is of little use - I need to know today.”

How Do You Measure Welfare?

Constant 24-hour close circuit television, webcams, thermometer readings and food and drink consumption figures are sent to a central computer in the farm office where the data is used to calculate a welfare score.

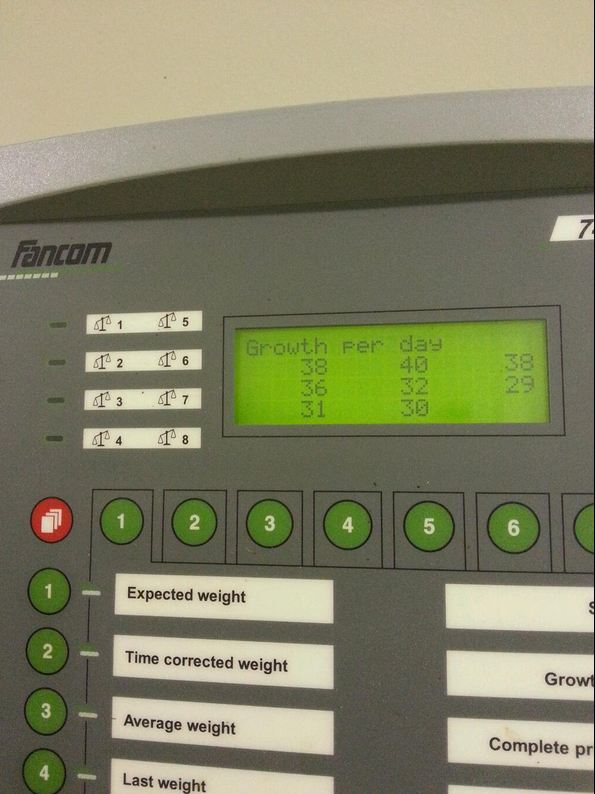

By embracing technology and getting on board with Dutch livestock IT and automation company Fancom, David can answer very specific questions about the welfare of his birds.

A percentage welfare value is assigned at a flock level by monitoring thermal comfort, bird movement, mortality rates, air pressure/humidity and absence from prolonged hunger/thirst, explains David.

This is given as a percentage, although is not able to single out a particular bird over David’s range of owned, rented and contract farmed units.

“We cannot calculate welfare for each individual bird,” he says. “What we can do is monitor important factors - such as water intake and apply it to the group.”

“If the shed is drinking to a target, there is a belief that every bird should be drinking.”

Currently, the day to day welfare score for a shed is 95-96 per cent, with David admitting that 100 per cent is fundamentally impossible.

“There is always a compromise with welfare the minute you put an animal in a shed. Even in free range organic production its welfare is being affected by artificial fencing,” says David.

But it’s not just the birds that benefit, David’s profits do too.

With Progress Comes Savings

If David can look at a monitors in the farm office and know what bird water intake is, what the temperature is like in all his sheds, he can then target the one with the problem. This takes a lot of the hassle out of management for David and his team.

David says this is vital in an industry that moves at a rate of knots, as he can identify which breeds may be more suited to slightly different styles of management.

“Because genetic progress is so rapid in this industry, we need to pull out data and react to it,” he explains.

He fears that two years could be wasted analysing performance to come to conclusions about a breed’s merits only for companies like Cobb and Aviagen to have altered the breed.

What David is able to do however is take daily live weight gain measurements via his automatic scales.

This gives him a snapshot of how birds are developing and what anomalies exist in the flock.

David’s reasoning for this is simple: “The more uniformity in size, the better it is for my customer and the more I get paid.”

Such an approach is not new to David, familiar with scrutinising size and colour of onions from his arable days.

Other installments such as David’s under-floor heating system and carbon dioxide sensors show how it pays to embrace technology.

Measuring CO2: One of the First

David was one of the early adopters of CO2 sensors, and while costing £1500, David asserts that, on the scale of a big business, the sensor made financial sense.

And David adds: “Nowadays, CO2 sensors are very commonplace on broiler farms and with the EU directive we want to be under 3,000 parts per million. Our sheds currently run at around 2,200 parts per million.

“It is good to keep CO2 under that 3,000 level anyway because I know I take a financial hit if it reaches 4,000 as bird productivity drops.”

The underfloor heating was another early installment which improved bird welfare.

It was a reaction to a lot of research showing the benefits of maintaining floor temperature at 30 degrees for chicks, explains David.

"When I thought about it, it no longer made sense to heat the air to ensure a certain temperature on the floor. Why heat air to 34 degrees to get 30 at ground level??

Going forward, David’s projects will continue to develop as part of a modern approach to asking how technology can improve farm efficiency and feed the world.

“I believe my lack of poultry experience has helped me to evaluate what could be done without any restrictions on my thoughts and ideas,” David concludes. “My arable background, particularly the vegetables, prepared me for technology.”