Field Vaccination for Respiratory Disease: Spray or Pump?

GLOBAL - Day-of-age spray vaccination at the hatchery is widely accepted by most US poultry veterinarians, but the best mode of field vaccination for respiratory diseases, especially infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT), continues to be debated.

Water-pumped, chicken-embryo-origin (CEO) vaccination in the field has been the “gold standard” for ILT for years. Some veterinarians have also reported that vaccination through in-house drinker-line medicators is effective.[1]

What’s been my experience? At Sanderson Farms, we’ve encountered practical problems when ILT CEO field vaccines are administered through the drinking water but not when the vaccines are applied with a backpack sprayer. In fact, our veterinarians have found that spray is the preferred application method for ILT CEO vaccines for several reasons.

Sampling of problems

For example, one of our growers mistakenly put acidifier instead of stabilizer in 100 gallons of drawn water, which killed the vaccine virus, but the error wasn’t discovered until a week after vaccination — a time when birds didn’t just snicker, they died due to ILT. At another farm, water-line regulators were ruined when high-pressure vaccine water was pumped through without proper adjustments.

More recently, after recombinant ILT vaccines were introduced, unexplained clinical ILT occurred in a flock that received both recombinant ILT vaccination in ovo and water-pumped field ILT CEO vaccination. The vaccination plan was intentional; we were transitioning from a recombinant to a CEO vaccine. We’ve found it is not typical to see birds dying from ILT after CEO vaccination, regardless of the administration route.

For best results, water used for vaccination — preferably 100 gallons — needs to be drawn up the day before vaccination and stabilized to remove any residual disinfectants, such as chlorine in community water. As noted earlier, pumping vaccines through the water lines can blow line regulators if care isn’t taken with each water line.

When using medicators, you’ve got to have medicator equipment for every house to accomplish vaccination across a farm on a given day. However, drinking-water medicators can malfunction, which delays timely, whole-farm vaccine exposure.

Comparing water to spray vaccination

In contrast to water vaccination, we haven’t had many unexpected consequences or undue reactions with our flocks when ILT CEO vaccines are sprayed in the field, even during two regional outbreaks of the disease.

Only one service person is required to administer spray vaccination, but at least three people should be present for pumped drinker-water vaccinations — one to run the pump and two more to turn the drinking equipment on and off. As we all know, many chicken farms don’t have three available workers and have to use integrator service personnel.

Spray vaccination typically takes less than 5 minutes per house, without previous flock preparation. The only equipment necessary to spray-vaccinate is the sprayer itself, which is kept and maintained by company personnel. Water vaccination requires hours of water deprivation and takes hours to administer, whether medicators are used or the vaccine is pumped directly into the water lines.

Proper technique

Of course, spray vaccination requires proper technique whether flocks are being vaccinated for ILT or any other disease, and spray equipment has to be maintained. Here are a few other suggestions:

- Make sure sprayer tanks and lines are free of unwanted bacterial contamination as well as residual disinfectants, which can harm the vaccine virus or the birds during vaccination. Spray equipment should be cleaned and rinsed prior to use.

- Check sprayers before each use and at least once during the day when in use to make sure spray output is adequate because accumulated chicken house dust can occlude air intake and/or exhaust ports; this, in turn, can restrict gas engines, which then won’t propel vaccine-laden water as originally designed.

- To spray uniformly, darken houses to immobilize the flock. Darkening houses is easy with black curtains or solid walls; the house lights are simply dimmed lower than routine settings. However, broilers in houses with clear curtains must be spray-vaccinated before dawn or after sunset to obtain adequate flock immobilization.

- Turn off house fans while the vaccine is applied.

- Make sure all house equipment is returned to original settings after vaccination; to ensure this is done correctly, farm managers should be present during vaccination because they best know how to properly operate their equipment.

Handling vaccines

Any field vaccination, whether it’s administered in water or sprayed, requires proper handling of vaccines and water for dilution. Viral vaccines should be kept cool and dark until the very last minute before mixing.

Water used for dilution should be free of disinfectants, bacteria and oxidizing minerals (e.g., iron), and kept cool as well. Farm source water is problematic; most farms have well water, and the quality can vary greatly from well to well, even on the same property. Even with a stabilizer, some dissolved components, such as iron, may damage vaccine viruses.

Often distilled water is used for dilution, but even distilled water can have pH ranges that are harmful to viruses. It’s wise to test water used for diluting vaccines when considering a new source.

In summary, when field vaccination is needed to maintain broiler respiratory protection, I’d recommend producers consider spray instead of water vaccination if they haven’t done so already. With careful attention to detail, there should be few to no problems with live viral vaccines that are sprayed.

[1] Garrity C. ILT Vaccination: Fact vs. Fiction. Poult Informed Prof. 2008 May/June;99:2-5.

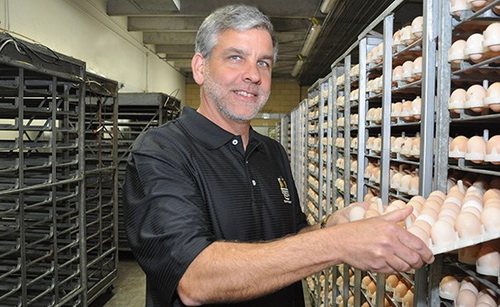

Philip A. Stayer, DVM

Corporate Veterinarian

Sanderson Farms, Inc.