Working with FSIS to Reduce Condemnations and Cut Losses

GLOBAL - Unnecessary condemnations can cost poultry producers a fortune. In some cases, poultry companies don’t monitor carefully enough to recognize off-target condemnations.In other cases producers know their condemnation rate is high, but what to do about it presents a conundrum. They don’t know how to go about challenging unsupportable inspector decisions or hesitate to do so because they fear retaliation, reports Douglas L. Fulnechek, DVM, Senior Technical Services Veterinarian, Zoetis in an article for Poultry Health Today.

As a former supervisory veterinary medical officer with USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), I can tell you that conducting regular condemnation reviews and taking action to reduce unnecessary condemnations is worthwhile.

The FSIS inspector’s job is to follow the criteria for condemning a carcass, but there’s a lot of judgment and subjectivity that goes into inspecting chickens and it can be difficult to make a quick decision about whether or not a carcass should be condemned.

Drawing on my hands-on experience in many poultry-slaughter establishments, I have seen off-target condemnation rates as high as 75%. In other words, three of four condemned poultry carcasses probably could have been salvaged or allowed to remain on the evisceration line.

For a facility processing 1.3 million 6.35-pound broilers weekly, the difference in loss between a 0.15% and 0.25% condemnation rate is staggering. If we factor in annual costs to maintain live-production volume, higher fixed costs at the plant for processing carcasses that are later condemned and, of course, the lost sales revenue, total annual losses from unnecessary condemnations can easily exceed $700,000.

Candid conversations

The first step toward reducing condemnations should be a candid conversation among live-production management, processing-plant management and FSIS veterinary supervisors. There has to be acknowledgement that post-mortem inspection is a process involving human judgment and the goal is to minimize errors, which to some extent are going to be inevitable from time to time.

Everyone involved needs to commit to routine weekly and monthly condemnation monitoring. To help maintain awareness of condemnations and keep everyone on their toes, I recommend having a processing-plant employee — perhaps a shift manager — discuss one or two whole-carcass condemnations with the FSIS veterinary supervisor weekly. Then, at the regularly scheduled monthly review, managers from live production, processing and FSIS can look at a significant number of condemned carcasses — about 10 condemned carcasses from each inspector. The live-production manager’s presence makes these sessions even more meaningful because it’s an opportunity to talk about flock-health programs.

Gather data

FSIS personnel record condemnations on a Lot Talley sheet and then summarize the information on a Poultry Condemnation Certification form, which is given to processing-plant management. The information on these forms can help producers track condemnations and, sometimes, leads to the cause of condemnation discrepancies.

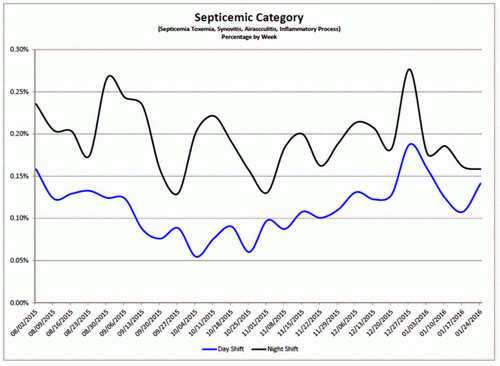

Figure 1 shows how condemnation data can be applied. It compares day- and night-shift condemnations for septicemia at a large, young-chicken processing facility. The data are aggregated by week over a 6-month period, so individual flock variation is negligible. Total carcasses inspected are about 17.5 million on each shift.

In this case, the difference between the day- and night-shift inspections is 0.08198%. That seems small, but considering the annual cost to maintain live-production volume, higher fixed plant costs and annual lost sales, it adds up to over $500,000. This information makes it clear the cause of condemnations wasn’t a live-production problem because, if it were, it would affect both shifts.

It appears instead the night shift was condemning carcasses that could have been salvaged — or perhaps there’s something going on during processing that’s causing too many carcasses to be condemned. These are clearly findings that warrant further investigation by the poultry company.

Figure 1. Comparison of carcasses condemned for septicemia during the day and night shift over a 6-month period

In a case of inappropriate condemnations I investigated, I found that one inspector condemned 80% of cadavers. The other seven inspectors accounted for the remaining 20%. As noted earlier, evaluating carcasses can be highly subjective.

Challenging inspector decisions

Poultry companies and FSIS personnel need to build mutually respectful relationships —and that, of course, takes time. When a poultry company believes there are off-target condemnations, the first step should be a talk with the FSIS veterinary supervisor. FSIS encourages processing plants to submit appeals in writing, when possible, because it establishes a paper trail, but written appeals are not required and I think it’s better to start off with an informal chat.[1]

During this talk, be prepared with charts, facts, data and even an example carcass. FSIS inspectors must be able to describe their observations and explain their decisions to the veterinary supervisor. It’s not acceptable for inspectors to only say a carcass is septic and needs to be condemned.

Basic relationship principles should be kept in mind when questioning inspector decisions. In addition to mutual respect, FSIS defines these principles as maintaining open, honest and straightforward communication, being issue-oriented with no personalizing, maintaining a work environment that’s absent from fear of retaliation and intimidation, and understanding each other’s roles and responsibilities.[2]

Formal appeal

If an informal talk doesn’t correct the situation, a formal appeal should be filed in writing to the next level, which is the frontline supervisor, who may or may not be a veterinarian. The appeal should include previous attempts to resolve condemnations. Attempts at resolution should be discussed during the weekly meetings between management, FSIS and live production. This approach won’t lead to salvage of carcasses already condemned but could change the pattern for the future.

Remember that inspectors and FSIS veterinary supervisors are human, so not all have the ability to suppress their emotions when condemnation challenges are raised. The retaliatory measures that poultry companies fear — vague threats of regulatory-control actions, issuance of frivolous Noncompliance Records, stopping an evisceration line for dubious reasons or performing pre-operational sanitation inspection at a pace so leisurely that it causes the production line to start late — are rare but have, unfortunately, been known to occur.

I’m aware of an FSIS manager who withheld inspection and caused 1 hour of lost slaughter time because his parking spot was inadvertently taken by someone else. This is very unusual, but it’s an example of behavior that should be documented and reported to the district manager. Witness statements and any other evidence should be included.

Another option is reporting such incidents to the USDA’s Office of the Inspector General, but it could take longer for a resolution. If there’s a fear of retaliation when submitting a formal appeal, note it in writing. FSIS doesn’t tolerate retaliation or intimidation by their employees, and legitimate complaints with supporting evidence are investigated and often result in disciplinary action.

You’re most likely to find, however, that FSIS inspectors as well as their veterinary supervisors approach their job in a professional manner and do their best to adhere to the established criteria for condemnations. When approached respectfully, they make a concerted effort to address problems.

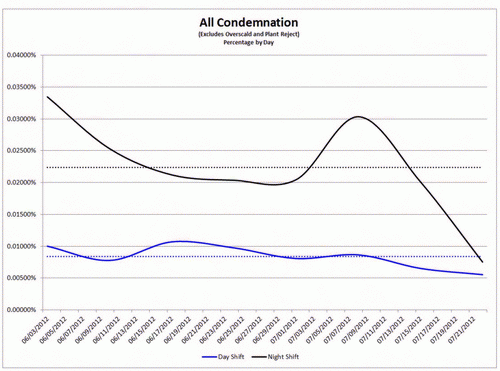

If you’re not convinced that working with FSIS is worthwhile, check out Figure 2. It shows the results of monitoring and addressing off-target condemnations. Routine reviews can pay off.

Figure 2. Reduction in condemnations during a 7-week period when routine reviews were implemented

[1] FSIS Compliance Guideline for Small and Very Small Plants Appealing Inspection Decisions.

[2] FSIS Directive 4735.7 Attachment 1. Relationship Principles.