Poultry science department builds faculty teams to face complex industry demands

The University of Georgia’s Department of Poultry Science is is tackling the foremost problems in Georgia’s valuable poultry industry.

In August 2020, Rami Dalloul joined the university as the first R. Harold Harrison Distinguished Professor in Poultry Science. Dalloul came to UGA from Virginia Tech, where he was renowned for combining the expertise of poultry research specialists across the globe to shape interdisciplinary teams.

At UGA, Dalloul focuses on a project that combines the research powers of the Department of Poultry Science, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) and the UGA College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) Poultry Diagnostic and Research Center (PDRC).

Collaborative research for the antibiotic-free industry

The project addresses complex and interrelated poultry intestinal diseases that require collaboration across disciplines. Primary among these diseases is poultry coccidiosis, an issue that has existed within poultry for many years but has been largely controlled by approved drugs, one of which was an early vaccine produced at UGA. However, the poultry sector’s movement away from the use of antibiotics has presented the need for new treatment options.

“Poultry coccidiosis is not one of those flashy diseases like avian influenza where you have to condemn thousands and thousands of birds, but it occurs mostly at subclinical levels. It’s caused by a very ubiquitous parasite found in almost every broiler house in the U.S.,” Dalloul said. “What it does is infect the guts where the parasites invade the cells within the intestinal lining and eventually kill them. As a result, those cells are no longer there for digesting feed and absorbing nutrients to help support the growth of the bird. Instead, resources are redirected to replenish those cells to get the bird back to full function.”

Because the parasite disrupts the birds’ intestinal systems, poultry coccidiosis can affect weight gain and therefore reduces profitability for poultry producers and, in some severe cases, causes birds to die. The impact of the poultry coccidiosis issue is exacerbated by a condition known as necrotic enteritis, a separate disease caused by bacteria that grow almost everywhere, like inside a chicken’s gut.

Dalloul explained that while many birds already have these usually harmless bugs in their intestinal systems, certain compromising conditions, like coccidiosis, can cause the bacteria to begin producing toxins and cause necrosis. Necrotic enteritis is not a new disease, but it was under control for many years until the discontinuation of certain antibiotics in the industry produced conditions conducive for the bacteria to flourish. The partnership between UGA poultry science, CVM/PDRC and USDA-ARS focuses on identifying alternatives for controlling these diseases without antibiotics.

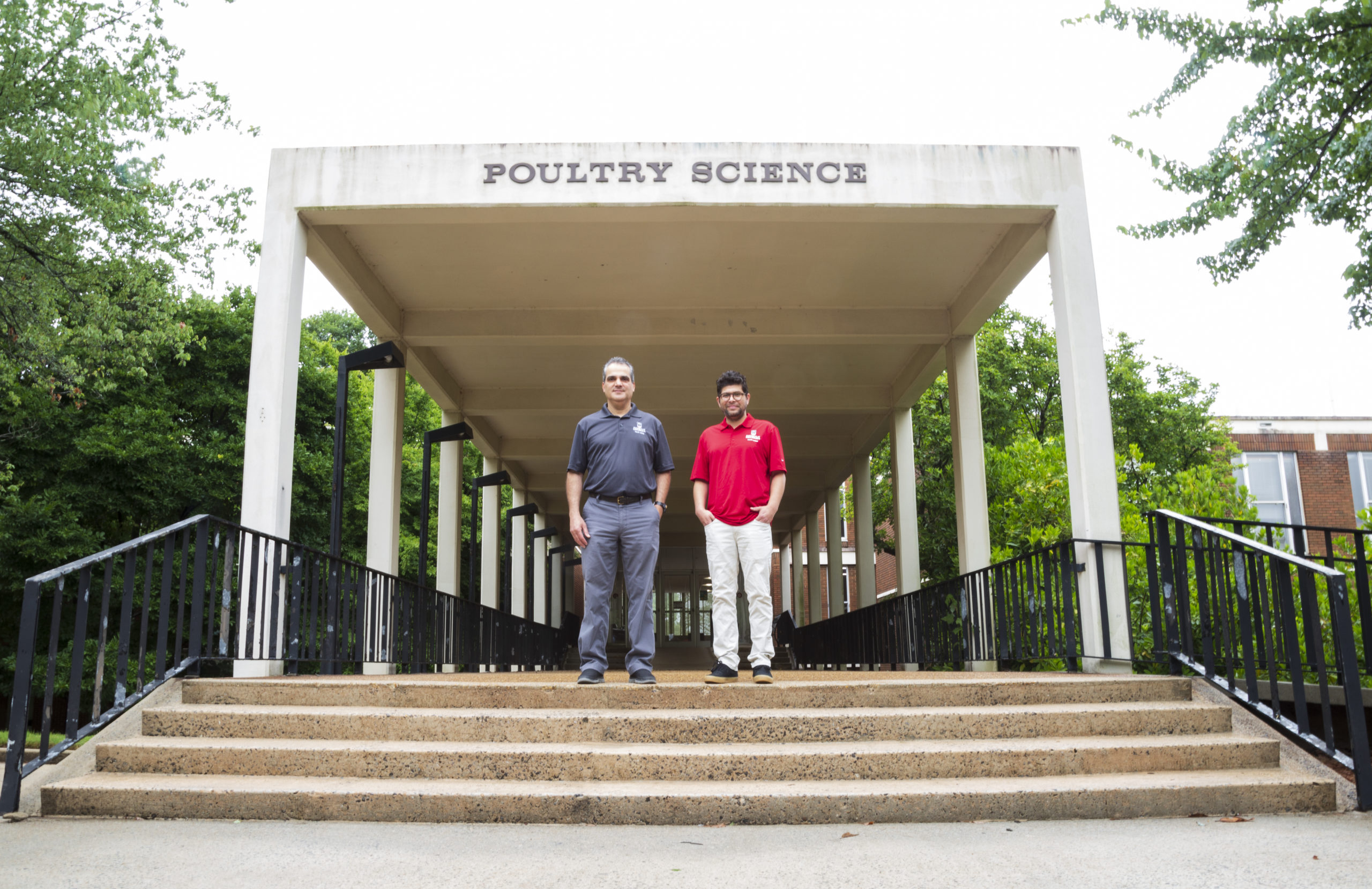

Professor Rami Dalloul joined the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences in August 2020 and is leading research into poultry coccidiosis.

“We have to evolve with the needs of the industry, and we are at the point where we need the alternatives,” Dalloul said. “Our department and other scientists have been investigating several alternatives to antibiotics mostly through in-feed application. However, hesitation by the industry to incorporate potential feed additives as antibiotic alternatives are due in part to inconsistent outcomes in the field, lack of documented physiological and microbiological effects, and limited understanding of their specific modes of action in the birds.”

Through the strategic partnership, interdisciplinary team members are using their specialized areas of research expertise to examine the effectiveness of in-feed antibiotic alternatives in various sectors of bird health. Dalloul explains that this approach allows the team to collectively tackle complex questions from biological and practical application angles to provide effective solutions.

“Many scientists work separately on the same problem. We each have our own little niche investigating very specific aspects. That’s why there is hesitancy in the industry in this case to implement experimental findings,” said Dalloul. “What we’re trying to do here is bring all of our collaborative efforts into one large project so we can tackle every aspect as we go along with these studies.”

By bringing in USDA-ARS experts and faculty members from across UGA, each researcher can collect their own samples during a study using a particular in-feed additive. Then, the researcher can run tests related to their area of expertise. These separate trials within the same study provide a more holistic view of the larger implications of implementing an innovation.

"When producers see something like this they say, ‘The University of Georgia has studied all these aspects we are interested in for this particular additive. Now we can adopt this additive commercially,’” Dalloul said.