Purdue researchers develop antibiotic-free treatment for avian pathogenic E. coli

Bacteriophage treatment reduces APEC in treated chickensPurdue University researchers in the College of Agriculture are developing patent-pending, antibiotic-free treatments for avian pathogenic E. coli, or APEC, according to a news release from the university.

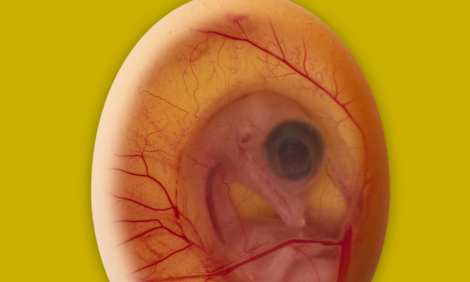

Paul Ebner and his team have developed a bacteriophage treatment that effectively reduces colonisation of APEC in treated chickens. The treatment contains multiple bacteriophages, which are viruses that infect and replicate only on bacterial cells.

Ebner is interim head and a professor in the Department of Animal Sciences. He said the goal of the project was to create technologies that could reduce the use of antibiotics in animals raised for food in low- and middle-income countries.

“APEC is often controlled through antibiotics, but the continued emergence of antibiotic resistance has led several countries and regions to prohibit many types of previously approved antibiotic uses in poultry production,” Ebner said. “We believe that the use of our treatment, along with good flock management, can significantly reduce the need for antibiotics in maintaining bird health.”

Ebner disclosed the bacteriophage APEC treatments to the Purdue Innovates Office of Technology Commercialization, which has applied for a patent from the US Patent and Trademark Office to protect the intellectual property.

The Purdue APEC treatment

Ebner’s team isolated seven bacteriophages that showed activity against the most prevalent APEC variants.

“Taken together, they lysed 90% of the APEC strains we tested,” Ebner said. “When given to chickens, the treatment results in significant reductions of APEC in the treated chickens’ lungs and ceca. Additionally, the treatments do not negatively impact growth or performance, and the birds do not develop an immune response to the phages.”

Ebner and his team used a microencapsulation process to allow oral delivery of the treatment. The microencapsulation protects the bacteriophages from the harsh environments of the gastrointestinal tract, including low pH levels and digestive enzymes, and allows more viable bacteriophages to reach the sites of infection.

The prototypes were developed for use in Pakistan and other low- and middle-income countries, but they have much wider applications. Ebner and Nicole Olynk Widmar, interim head and a professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics, conducted a willingness-to-pay study in Pakistan.

“The results showed consumers will pay premiums for chicken produced with bacteriophages instead of antibiotics,” Ebner said. “Additionally, we are working to identify barriers to adoption among poultry producers and animal health professionals.”