In the eye of the beholder

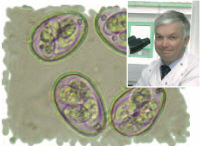

Eimeria is the object of Dr. Ralph Marshall's fascinationTo an outsider, studying Eimeria for a living is a far-from-glamorous job, but parasitologist Dr. Ralph Marshall considers the object of his work attractive, mysterious, clever and challenging. He even has a favorite coccidial species - Eimeria tenella.

"Under the microscope, it has the

most beautiful shape of all the Eimeria

oocysts and a beautiful blue halo. It's as

simple as that. I just love it," he says.

The scientist heads up coccidiosis

research at the Veterinary Laboratories

Agencies (VLA), an entity initiated over

100 years ago in a small London office.

Today, VLA is located in Weybridge,

England, and is an internationally

recognized veterinary research center.

It is a reference laboratory for many

farm animal diseases and conducts

important studies for pharmaceutical

companies.

Marshall came to VLA in 1971 and

compares his work studying Eimeria

to his favorite hobby - bird-watching.

"There are a lot of analogies between

the two," he says. "I love walking out

in the field and being able to identify

a bird. And I love being able to

look down a microscope and identify

a parasite. Both have taught me the

skill of observation, which is key to

parasitology."

Observation has also enabled him

to witness an array of interesting developments

over the years in the field of

coccidial research.

'Brave new world'

When anticoccidial chemicals were

developed and marketed, it appeared

to herald a "brave new world," he says.

Then the problem of Eimeria resistance

to anticoccidials started to develop.

Marshall spent several years studying

the problem.

"Slowly we realized that these little

parasites were winning. It was good

fun working out the mechanisms of

how the parasites were getting resistant

to drugs," he says.

"We managed to develop lots of

resistant strains here in the lab. We

actually had one that got hooked on an

anticoccidial. If we gave this particular

Eimeria strain to chickens that were fed

a particular anticoccidial, the parasites

lived. If we withdrew the drug, the parasites

died. The drug seemed to keep

the parasites alive," Marshall says.

Recalling the advent of ionophores,

he says, "The idea behind these

drugs was not to wipe out the parasites

completely."

Around that time, however, Marshall

experienced a time warp when he

moved to another department within

VLA and temporarily lost track of coccidiosis

research. He returned to his

beloved field in the 1990s to find a

newcomer on the scene: the attenuated

coccidiosis vaccine Paracox, which has

dominated his life for the past decade.

The poultry industry had difficulty

adjusting to the notion of vaccinating

poultry to control coccidiosis. "There

was a total change in mindset from

being told you have to get a drug to kill

this parasite to then being told that you

don't want to use a drug, you can use

a vaccine instead," he says. "That was a

difficult concept for producers to

grasp."

Today, coccidiosis vaccines are

widely accepted in the breeder sector

and in several countries, their use is

growing in other segments of the market,

including broilers and free-range

laying hens, Marshall says.

Testing sprayed vaccine

Eimeria photo courtesy of Dr. Ralph Marshall.

Marshall has also been involved in testing

new methods of administering coccidiosis

vaccines. About 6 years ago, he

headed up VLA's assessment of

Schering-Plough Animal Health's

SprayCox II, a spray cabinet technology

for application of Paracox-5 to broilers.

"We set up a cabinet that was like a

giant sort of construction kit," he says.

"We had about 700 or 800 birds that

were vaccinated in large groups at

once. Then we challenged them with

field strains of Eimeria given at times

ranging from about 2 to 7 weeks after

vaccination. It was very successful and

we published the results."

More recently, Marshall has been

involved in testing the efficacy of the

spray cabinet for administration of

Paracox-8 for broiler breeders as well

as free-range egg layers, a development

that would bring added convenience to

farmers vaccinating birds in this segment

of the market.

For the study, birds were challenged

with seven Eimeria species. The outcome

is being determined by performance

results such as weight gain as well

as oocyst output and lesion scores. At

this writing, the preliminary results

looked good, he says.

Another important aspect of

Marshall's work with coccidiosis has

been development of an anticoccidial

sensitivity test to determine the level of

resistance among Eimeria parasites

recovered from the field. Birds on various

anticoccidials are challenged with

Eimeria field isolates and, again, performance

and oocyst output and lesion

scores will be used to reveal the sensitivity

of each Eimeria species to the various

anticoccidials tested.

Studies in other countries, he notes,

have demonstrated that resistant field

strains of Eimeria can be replaced with

the strains of Eimeria in the vaccine,

which are still sensitive to anticoccidials.

In other words, the vaccine can be

used to revitalize a producer's anticoccidial

program or it can replace the

use of anticoccidials, which is especially

important for growers raising antibiotic-

or drug-free birds.

At this writing, Marshall planned to

initiate sensitivity testing soon. Similar

testing has been conducted elsewhere

in Europe and the United States, but

never before in the UK, he says.

"Our studies will demonstrate if the

experience in the UK is likely to be the

same as it has been elsewhere," he

says.

Eimeria's economic impact

Throughout the interesting twists and

turns that have occurred during his

career, Marshall never forgets the economic

importance of his work.

Eimeria and resulting coccidiosis

has been estimated to cost the UK

alone £35 million (51.5 million Euros or

$66.2 million) a year considering production

losses and the cost of anticoccidial

control, he says. "With inflation,

it's probably a lot more since that

figure was established. The disease

causes a huge, huge cost to poultry distributors."

Eimeria, Marshall points out, is tenacious.

If you leave coccidia lying on the

ground in a chicken house, particularly

in the UK where it's often cool and

damp, it can survive for weeks and

may resist normal cleaning and disinfection

processes. With short turnaround

times, this can present a problem

for subsequent flocks. "It can be a

very difficult bug to get rid of. The

industry has found ways to contain

Eimeria, but it comes with a price.

"We'll never know all there is to

know about coccidia. These parasites

are just too clever for us," he says.

There are also hidden costs from

coccidiosis that aren't even readily

apparent, Marshall says. Anticoccidial

resistance has resulted in a subclinical

challenge that knocks the edge off performance.

Trials in the UK have shown

that when broilers are vaccinated for

coccidiosis with Paracox-5 and that

challenge from resistant coccidia is

eliminated, growth appears to blossom

and there's an increase in live weight.

"Considering that we grow 800 million

broilers in the UK annually, better control

of coccidiosis through vaccination

could have a huge impact, but producers

here, understandably, want hard

data," he says.

Marshall's work with vaccines has

taken on new importance due to the

movement toward drug-free poultry

production. The arsenal of anticoccidials

is shrinking and, he predicts,

ionophore use may be reconsidered in

the future.

Producers still using anticoccidials

need to make the most of the ones that

are still available or they need to find

alternatives. If they know they can successfully

revitalize or replace their anticoccidial

program with vaccination,

"that would be great," Marshall says.

In addition to changes prompted by

the drug-free movement, animal welfare

trends are also affecting poultry

producers. More birds will be freerange

and the sizes of cages and the

number of birds reared on floors are

growing, which could increase the coccidial challenge. That's why Marshall

says vigilance is needed not only to

keep up with coccidiosis disease patterns,

but also to find improved control

strategies that help producers minimize

losses due to Eimeria.

Apart from VLA, Marshall plans to

be vigilant about traveling with wife

Jackie, adding to the list of 40 countries

they've visited so far.

His most exciting trip was a safari in

Botswana - hands down. "The animals,

birds and ecology are fantastic,"

he says.

Asked what observation in the bird

world compares to the excitement of E.

tenella's blue halo, though, and

Marshall says it was finding a nesting

pair of black stilts in New Zealand,

probably the rarest shorebird wader in

the world.

"There are only about 80 of these

birds left in the world, and I observed

a breeding pair," he says.