Combating Resistance

Vaccination seeds houses with oocysts that are sensitive to commonly used in-feed coccidiostats

Poultry producers confronting

resistance to in-feed coccidiostats

can minimize the problem

by incorporating coccidiosis vaccination

into their management plan, says

poultry veterinarian Dr. Linnea J.

Newman.

Continuous and long-term use of infeed

ionophore coccidiostats has resulted

in resistance and less effective control

of coccidiosis, which is caused by

protozoan parasites of the Eimeria

genus, says Newman, a consulting veterinarian

for Schering-Plough Animal

Health. Resistance results in impaired

performance, particularly poor weight

gain.

However, rotating coccidiosis vaccination

with the in-feed products

"seeds" the houses with oocysts that

are more sensitive to the in-feed treatment,

she says.

Changes Oocyst Population

Coccivac-B, Newman explains, is a live

vaccine produced with oocysts that

were isolated before currently used

coccidiostats were even developed.

Consequently, birds that receive this

vaccine shed oocysts that are sensitive

to the in-feed coccidiostats widely used

today by poultry producers.

"In other words, the vaccine can be

used to change coccidiostat-resistant

populations into coccidiostat-sensitive

populations," she says. "The oocysts

that result from vaccination, in fact, are

extremely sensitive to both chemicals

and ionophores, yet they are not as virulent

as some of today's coccidiostatresistant

field isolates."

Clear Evidence

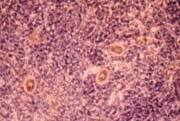

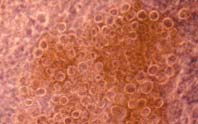

As evidence, Newman points to

Eimeria maxima

|

She also cites trials conducted by Dr. Harry D. Danforth of the USDA (see feature on page 6), which further demonstrate that vaccinating with Coccivac-B renews the sensitivity of an on-farm coccidial population to the ionophore salinomycin, the most widely used coccidiostat in the United States.

Eimeria acervulina

|

Next, sensitivity to salinomycin was tested. One group of specific- pathogen-free (SPF) birds was challenged with oocysts from the vaccinated houses, and another group of SPF birds was challenged with oocysts from the ionophore-treated houses. During the challenge, all birds received 60 ppm of salinomycin.

Weight Gain Improved

Comparison of the two groups revealed much better weight gain in the birds

Eimeria tenella

|

More recent studies by Danforth indicate that vaccination can not only restore the sensitivity of oocysts to coccidiostats, but that it changes the composition of mixed species oocysts in the field and their ability to cause intestinal damage, Newman says.

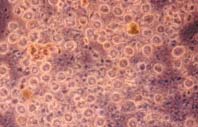

For instance, an aggressive strain of Eimeria tenella and a moderately pathogenic E. maxima were isolated from litter samples collected from a farm at a large broiler integrator. After the samples were collected, a new flock was

Mixed-species oocysts

|

The mixed-species oocyst population from each sample was isolated and used to challenge 10-day-old SPF test birds fed nonmedicated or salinomycin- medicated feed. Six days after the challenge, the birds were weighed and intestinal lesions were recorded. "Following vaccination with Coccivac-B, the aggressive E. tenella population had virtually disappeared," Newman says. Before vaccination, the E. tenella was considered very aggressive and created high lesion scores, even in salinomycin-medicated birds. It should also be noted that 3-Nitro (arsenelic acid) had to be used routinely to augment the ability of ionophore coccidiostats to control E. tenella, she says.

Lesion Scores Improve

After immunization, lesion

scores for the middle and

upper intestine due to E.

maxima and E. acervulina

had improved in salinomycin-

medicated birds,

which indicates that vaccination

had an impact on

these species of Eimeria

and that each species had

improved sensitivity to salinomycin

after vaccination.

Coccidiosis vaccination can not only

be rotated with coccidiostats, it can be

an alternative to these in-feed products,

Newman says.

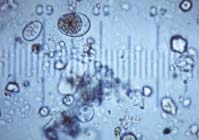

Vaccine Fosters Natural ImmunityIn-feed coccidiostats prevent coccidiosis by disrupting the parasite's life cycle, but vaccination enables chicks to develop natural immunity to coccidiosis infection, Dr. Linnea J. Newman explains.Immunity develops when birds are exposed to infected oocysts passed in droppings. "It takes about two or three cycles of mild infection to provide immunity adequate enough to protect chicks from later field exposure to coccidia," she says. Vaccination is more likely to be successful today than ever before because better methods of administration have been developed. For example, spray cabinet administration on hatching day helps ensure the vaccine is administered evenly to chicks, which in turn helps development of immunity in a flock and protect against coccidiosis outbreaks, she says. |

Source: CocciForum Issue No.2, Schering-Plough Animal Health.